Tired Old Brands Can’t Stomach Amazon-Whole Foods

Tired Old Brands Can’t Stomach Amazon-Whole Foods

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here’s to the losers.

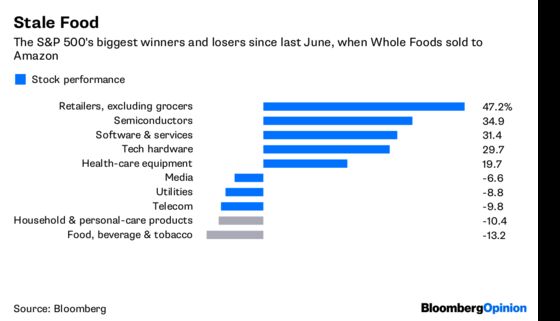

Packaged-food and consumer-products companies—including heavyweights like Kraft Heinz Co. and Procter & Gamble Co.—are the worst-performing basket of stocks in the S&P 500 Index over the past year. It’s no coincidence that it’s also been a year since Amazon.com Inc. agreed to buy Whole Foods.

In Amazon’s defense, it’s hard to find a direct link between anything it’s done so far and the pain suffered lately by the suppliers that have traditionally dominated grocery store shelves. As Shira Ovide notes, Amazon has actually done little with Whole Foods since the deal closed. But even if the fear of Amazon is disproportionate to its actions, Sarah Halzack explains how the secondary effects of its $13.7 billion grocery gamble are already being felt throughout the industry.

Knowing that Amazon is lurking, supermarkets are trying to be more competitive with their prices, product offerings and services such as delivery, and that pressure has made its way most meaningfully to the manufacturers. Underpinning all this is the desire among more shoppers for fresher, organic and trendier items—from chia-seed-almond-milk yogurt pods to bio-based detergents and kombucha. It makes companies named for canned soup and single-serve processed cheese slices sound passe.

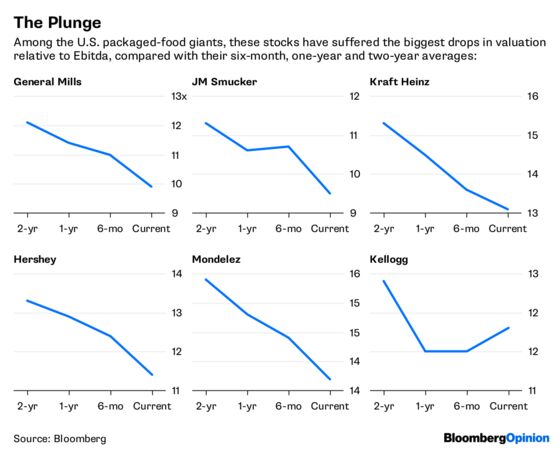

Their stocks are getting cheaper because profits aren’t contracting as quickly as their share prices would suggest. That doesn’t necessarily make them bargains:

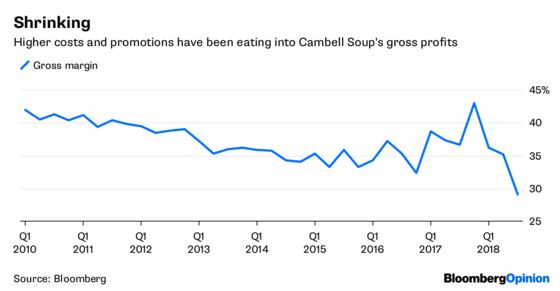

Campbell Soup Co. once controlled more than half the U.S. soup market. Now, its gross margin—a measure of pricing power— has contracted to 29 cents on every dollar of sales, versus more than 50 cents at the turn of the millennium. Last fall, just after Amazon completed its Whole Foods purchase, Campbell got into a spat with Walmart Inc. over a promotional program for the winter cold-and-flu soup season that significantly hurt its sales. Desperate to expand into more attractive segments of the food space, Campbell then paid an arm and a leg for Snyder’s-Lance, a maker of snacks. The debt-heavy deal has been unloved by shareholders and bondholders alike, and soon, I figured, its CEO would end up paying the price. Sure enough, Denise Morrison retired abruptly in May without naming a permanent replacement.

Campbell is far from the only grocery supplier feeling the pressure. Consider the absurd density of cereal aisles—just rows and rows of mostly sugary products that have waned in popularity, and Euromonitor International estimates the North American market for breakfast cereals will continue to shrink. Kellogg Co. and General Mills Inc. are having to think outside the box, with Kellogg pushing frozen foods and buying the RXBAR brand of protein bars, while General Mills turns to pet food. Investors haven’t been impressed with either yet.

Kellogg still calls its division comprising frozen foods, Kashi and RXBAR the “North America Other segment,” and it accounted for just 13 percent of total company revenue in the latest 12-month period. CEO Steve Cahillane, who took the helm in October, said last month that Kellogg “is busy getting back to basics and investing in what we know can grow.” It’s a mantra you’ll hear a lot.

For Kraft Heinz, that’s meant growing its profits by slashing costs, a strategy enabled by its enhanced scale. But nearly three years since the private equity firm 3G Capital merged Kraft and Heinz (with help from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc.), the company’s operating margin looks like it’s topping out. Its stock, meanwhile, has hit a low. Another megamerger may be the only way to continue delivering the earnings growth its investors have enjoyed—but at what cost? And will it have the financial backing of Buffett for the next deal? I’m not so sure.

It’s not just food feeling the pressure. P&G, the behemoth of the household-products industry, was forced to cut prices on its value-oriented Luvs diaper brand in response to what it says is aggressive competition, fueled by a slow-growth environment for conventional brands. Colgate-Palmolive Co., home of the namesake toothpaste and dish soap, cut its long-term organic-growth goal to 3 percent to 5 percent, down from 4 percent to 7 percent. Sales at Kimberly-Clark Corp., the maker of Cottonelle toilet paper, were lower in each of the last two years than during the recession a decade ago. It’s shutting down some factories to save money.

General Mills CEO Jeff Harmening, who took over from Ken Powell a year ago, said in November that companies just need to go where the growth is to maintain strong relationships with chains such as Walmart and Kroger Co.:

“What I would tell you is what I find from our retail partners, they're all looking for one thing. That is growth. And if you can help, if you can partner with your retail customers to help them grow their business and your business at the same time, you're going to have a lot of success. If you can't do that, it's going to get rough.”

Until pretty recently, these companies haven’t had to justify their shelf space. Now they’re being forced to adopt a new mindset. And when Amazon really starts in with Whole Foods, what then? For some of these lumbering giants, it is indeed going to get rough.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.