Amazon’s Self-Interest Opens Up Its Books a Crack

Amazon’s Self-Interest Opens Up Its Books a Crack

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I’ve chided Amazon.com Inc. for its useless financial “disclosures,” particularly around its annual Prime Day hoopla. But in Amazon’s April letter to shareholders, the company for the first time gave crucial information that allowed outsiders to work out the value of merchandise sold on the company’s digital mall and the chunk from businesses that use Amazon as a sales conduit.

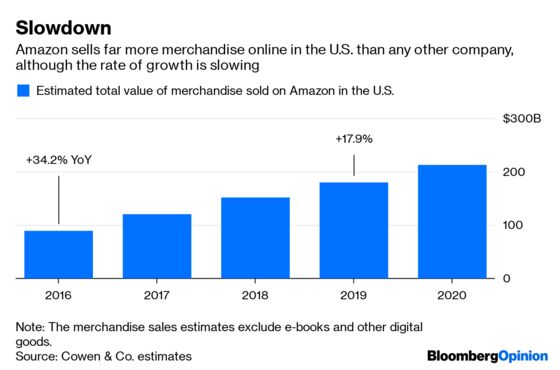

My first takeaway from these disclosures was that Amazon’s growth was slowing considerably. But those figures contained two other messages, one explicit and one implicit: that Amazon isn’t as big as people had thought and that it’s more of a middleman than a conventional retailer.

Those were sly rebuttals to growing criticism that Amazon is the big bully of online shopping. And the timing was fortuitous.

The disclosures spurred research firm eMarketer to drastically downsize its widely cited estimate of Amazon’s market share of U.S. online shopping, from what had been nearly 50% expected this year to 38%. I don’t know whether Amazon intended its shareholder letter to nudge eMarketer, but with regulators and politicians questioning the power of Amazon and other U.S. technology giants, it is a good thing for Amazon to appear smaller.

Amazon Chief Executive Officer Jeff Bezos also explicitly used the shareholder letter to talk up the small businesses that sell slacks or boccie balls on Amazon in return for giving a cut of sales and other fees to the e-commerce giant. Bezos disclosed for the first time that those merchants are behind 58% of the goods sold on Amazon. Bezos made his spin clear: Those merchants are kicking Amazon’s butt, as he put it.

That bolsters a point the company loves to make. Amazon in its view is not a killer of Main Street retailers but their friend — a place for them to reach hundreds of millions of eager shoppers with Amazon’s able help. This message does double duty with Wall Street. Investors are happy if Amazon becomes more of a sales conduit and less of a conventional retailer that buys blenders from manufacturers and sells them at a markup. Amazon is far more profitable as a middleman.

But the companies supposedly doing this butt-kicking don’t necessarily feel so mighty. The European Union’s anti-monopoly authority opened a formal investigation on Wednesday into whether Amazon unfairly uses its power to advantage itself at the expense of merchants and product manufacturers that rely on the e-commerce site for sales.

At a congressional hearing this week, legislators also peppered an Amazon executive with questions about whether the company uses data gleaned from its vast digital mall to decide what products to make under its own brands or to otherwise thwart competition, or whether it arbitrarily suspends merchants from selling on Amazon with little visibility into how to appeal the decision.

Whatever Amazon’s market size is, it doesn’t necessarily insulate the company from regulatory questions about its behavior— whether it has the power to set the financial terms and rules for merchants and brands that sell goods on its site, or change them at will, in ways that may advantage Amazon.

Amazon may emerge from this scrutiny relatively unscathed, although it did promise changes to seller terms on Wednesday to address issues raised by German and Austrian regulators. And regardless of the company’s motivation, it has revealed more about its finances in a way that helps people like me understand it better.

On Wednesday, I thought Amazon wasn’t disclosing anything useful about its sales during Prime Day, unless it’s useful to know that people bought more than 100,000 lunchboxes on a fake shopping holiday. But Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter pointed out on Twitter that he was able to roughly estimate both the total value of sales over Prime Day and the average amount spent on each item. Amazon’s previous disclosures about its total merchandise sales and the share from merchants aided those calculations.

It’s debatable whether Amazon’s Prime Day numbers were large. Based on Cowen analysts’ estimate that Amazon will ring up $344 billion in total merchandise sales this year, the company would average $943 million in sales in any given day, or $1.9 billion over the two days of Prime Day. Pachter estimated that Amazon racked up close to $5 billion in sales over the two-day sales event, or nearly three times the rough average. Impressive, although it’s worth asking whether some people bought an Echo speaker or bedsheets this week that they otherwise would have bought next week or last month.

And Amazon’s motivation for Prime Day seems to be landing more members for its Prime shopping club. Amazon said more people signed up for Prime during its fake shopping holiday on Monday than any previous day. Amazon put no numbers around this, of course. Given Amazon’s habit of financial obfuscation, I will continue to question how cherry-picked or nuanced its figures are.

Still, because Amazon has opened up a bit more with its financial disclosures — to suit its own strategic messaging — it’s easier for outsiders to paint a few more details on Amazon’s historically sparse canvas. And knowledge is power.

Coresight Research estimated Prime Day sales were about $5.8 billion in the U.S.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.