Amazon Flexes Its Well-Defined Muscle on Its Own Labels

Amazon Flexes Its Well-Defined Muscle on Its Own Labels

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In my medicine cabinet, I have a jar of petroleum jelly from Walgreens that looks like the iconic Vaseline container. You probably also own store-brand versions of familiar items — also called generics or “private label” products.

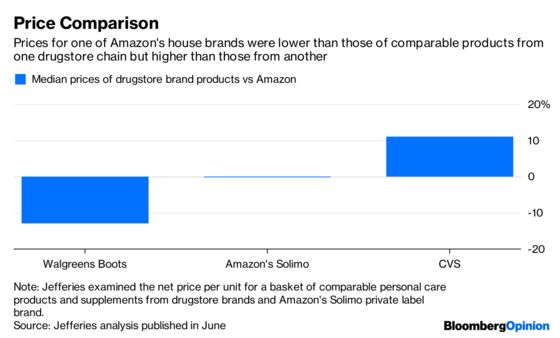

The pull tends to be lower cost, but Walmart, Macy’s and other big retailers have been seeking to create private-label products with a unique appeal beyond price. Think about the devotion for Costco’s Kirkland line, or Trader Joe’s store brands.

Amazon.com Inc. appears to be trying both conventional generics and private-label brands with their own identity. It’s straight from the old retailer handbook, but Amazon’s twist feels both savvy and a little icky.

The company has amassed more than 100 in-house brands, by some estimates. The Amazon line ranges from AmazonBasics for lower-cost versions of batteries and motor oil to the wannabe brands such as Rivet furniture, Daily Ritual clothing and Happy Belly pantry products. In recent days, Amazon got dragged into court over whether it improperly copied a West Elm armchair. An Amazon spokeswoman has declined to comment on the suit.

Private-label products can be legal if they don’t confuse consumers, but that doesn’t clear Amazon for making strikingly similar-looking furniture. Broadly, like nearly everything involving Amazon, its approach with private-label brands is both potentially great for shoppers and an opportunity to grab even more power for itself.

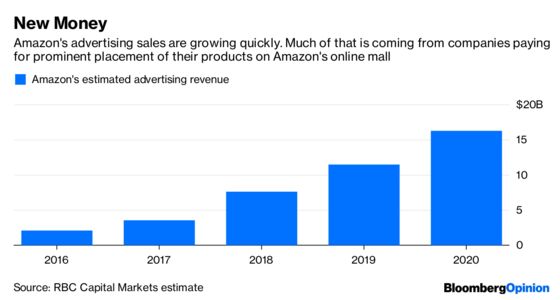

I did a search Wednesday for “Solo cups” on Amazon’s website, and the results came back with a prominent placement at the top of the page for Solo products — it was a paid advertisement from the company — and right below that Amazon took out its own ad for its plastic cups, which are less expensive. RBC Capital Markets analysts conducted 100 product searches on Amazon’s mobile app and found that one in six results were from companies that were paying Amazon to show up high in search results.

It feels like a good deal for shoppers, but it’s understandable if Solo doesn’t feel happy about Amazon selling a similar version and nudging people to buy it. (In a statement, a representative for Solo’s parent company said people chose its products for the quality and brand affinity and that private-label items provide shoppers choice and value.) Search for “dish soap” on Amazon’s website, and the first results you may see are paid placements for known brands plus a prominent lineup of Amazon’s own varieties of soaps.

Yes, conventional retailers do this, too. Walmart and Kroger can put their store brands in eye-catching spots on shelves, for example, and they charge big brands to stock their wares in prominent locations. But that brings me back to why it feels different when Amazon does this in the digital realm.

Amazon has more data on what people shop for than anyone else and can lure people to its own brands with house ads and software-generated product suggestions online and through the Alexa digital assistant and prominent online placements like in the Solo and Dawn examples. And those brands may feel compelled to pay Amazon for ads to ensure their products remain front-and-center when shoppers go looking for them. Amazon loves to say it only thinks about what’s best for shoppers, but is it good for shoppers to have top product listings dominated by companies that pay Amazon for prominent placement and Amazon’s house brands?

Walmart still takes a bigger chunk of total U.S. retail spending, but Amazon is rising fast, and that contributes to anxiety about the company employing the old retailer strategies with Amazon’s muscular twists. European anti-monopoly regulators recently started to make inquiries about Amazon’s private-label products.

An analysis earlier this year from Cowen & Co. estimated that Amazon’s store brands can generate 25 to 40 percent market share in a unique item within the first six months of sale, thanks in part to Amazon’s ability to push its own products. The Cowen analysis also said that if one of Amazon’s private-label products has weak sales or poor customer reviews, the company will let the product wither. That’s a classic Amazon tactic.

Amazon’s underlying opportunity in private label and beyond may be its ability to erode the allure of all brands. If I can’t find a West Elm chair or my favorite vitamins on Amazon, I might want that specific product enough to hunt for it elsewhere. Or maybe it’s good enough to buy Amazon’s version, which might even be produced by the same manufacturer. If Amazon can make itself the most essential place to shop, then only its brand matters.

In more recent searches, Solo's ad has been replaced by one for Hefty's brand of plastic party cups.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.