Airbnb, Vrbo Share Details on Party Houses, Not Violent Crime

Airbnb, Vrbo Share Details on Party Houses, Not Violent Crime

(Bloomberg) -- Airbnb Inc. and Expedia Group Inc.’s short-term-rental unit Vrbo announced in June that they were partnering to share information about repeat “party house” offenders. What they didn’t agree on was sharing details about properties they’ve banned after violent crimes have occurred there.

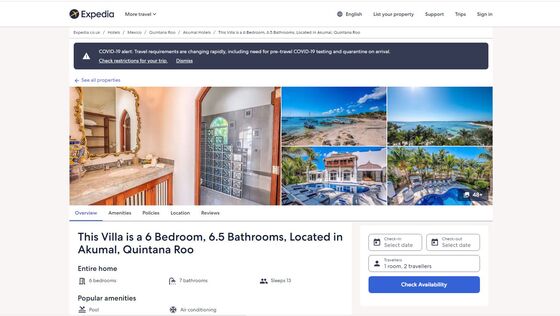

That became an issue this week after Expedia permanently barred a Mexican villa where a 35-year-old New York City high school teacher was found naked, bruised and near-death three years ago while on a summer vacation. The incident, first reported in a July 20 Bloomberg Businessweek story, led to an immediate lifetime ban of the villa and its host by Airbnb, the platform used to book the stay. But it was only after the story was published that Expedia became aware of what happened and removed the listing from its platform.

Unlike hotels, short-term rentals typically have no security guards or on-site support staff. It is up to the hosts who list their homes on the platforms to decide how they want to exchange keys with guests, who has access to the property and whether or not they want to install a smoke detector or put locks on bedroom doors. The lack of regulations has allowed short-term rentals to explode into the fastest-growing sector of the online travel market, collecting almost 30 cents of every dollar spent on hospitality today.

The platforms also aren’t required to share information about properties they blacklist, even when they take the extreme action of a permanent ban. So a property barred by Airbnb can still be listed on Vrbo or other platforms.

That’s what happened with the Villa Taj-Kumal on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula after Lauren Kassirer rented a room there in July 2018 and never made it home. The night before she was found, she texted friends to say she was afraid of a staff member at the six-bedroom villa where she was the only guest. She died at a Florida hospital 23 days later, never having regained consciousness. The cause of death was undetermined, despite bruises to her arms, inner thighs and genitals, and no one was arrested in connection with the case.

Airbnb quickly banned the villa, the host and other listings at the nearby Hotel Akumal Caribe, which owned the property. But earlier this year the villa popped back up on Airbnb under a different name. When Bloomberg notified Airbnb of the re-listing last month, the company removed it and said the host used “deceptive tactics” to post it through a third-party property-management firm.

Earlier this week, when Bloomberg notified Expedia about what happened at the villa, the company also removed the listing from its platform. “If we are made aware of a crime or safety issue that occurred during a stay booked on another platform our policy is to investigate and take appropriate action, including removing the property from our site and relocating any upcoming traveler bookings,” Dave McNamee, a spokesman for Expedia, said in an email.

That’s not good enough for Eli Kassirer, Lauren’s father, who decided to speak publicly about his daughter’s death for the first time in the recent Bloomberg story. “It’s scary to contemplate the fact that this listing might still be active,” Kassirer said. He said he fears other young adventurous travelers might book a room at the villa “without knowing the dangers that could be waiting there.”

Kassirer is calling for short-term-rental platforms to share information about banned properties. “I would hope there would be some way of monitoring and permanently de-listing any places that are deemed unsafe,” he said.

Any effort to do that would have to be voluntary because there’s no regulatory authority in the U.S. that can force short-term-rental companies to do so, said Arun Sundararajan, a professor of entrepreneurship at New York University’s Stern School of Business who has written books on the sharing economy. “Right now, every platform has its own process -- and its own blacklist,” he said. Sundararajan said a self-regulating industry consortium could enforce transparency across platforms and get the companies to share information about banned properties to prevent dangerous listings from hopping across sites.

The party-house agreement between Airbnb and Vrbo, its closest industry rival, is an example of that. With bars and nightclubs shut last year by Covid-19, some promoters booked homes on short-term-rental platforms to host events with live DJs and bottle service. The parties infuriated neighbors, spread the virus and, in some cases, resulted in fatal shootings.

Both companies tried to address the issue independently. But, they said in a joint statement announcing the Community Integrity Program in June, repeat offenders delisted by one platform can pop up on another. “One platform alone can’t solve this problem,” the companies said. “It requires an industrywide effort.”

The program is expected to begin in the U.S. later this year. Representatives for both companies said they have systems in place to guard against hosts re-listing banned properties on their own sites but have no immediate plans to expand the party-house program to include sharing information about listings that become crime scenes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.