What Climate Science Loses Without Enough Black Researchers

What Climate Science Loses Without Enough Black Researchers

(Bloomberg) -- Vernon Morris had often felt invisible in a profession defined by observation. As a climate scientist, he's encountered racist behavior at every level of his field.

Feelings of isolation marked his early days analyzing atmospheric ozone chemistry, with virtually no Black peers. Morris has weathered groundless police harassment, and repeatedly been mistaken for a janitor when working at NASA decades ago as a grad student. He was once stopped at a science conference, despite wearing a speaker name badge, as he made his way to the podium to give a speech. And Morris has felt the sting of everyday slights, such as when White scientists and students go out of their way to avoid eye contact.

“It’s that level of subtlety that we don’t want to call racism, but it’s the same,” said Morris, 58, founding director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center for Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology. “It’s the same substance that decisions are made on that exclude people of color.”

(About Morris’ experiences at NASA, the agency said it was unfamiliar with those events, and that “at NASA we have proven that unity, diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity are our strengths. We know we have more to do, and we’re committed to doing it.”)

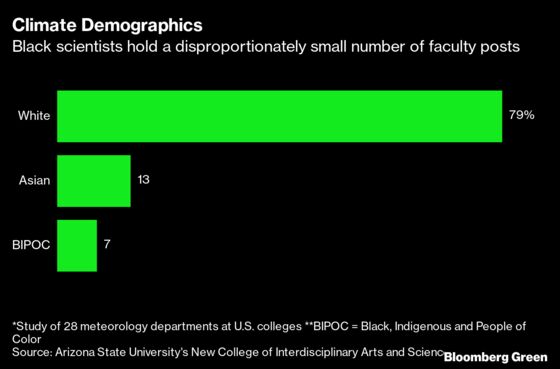

The geosciences, which includes climatology, is home to the least diverse population of PhD candidates among the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines, said Morris. The problem with U.S. climate science, Morris said, is the cohort of scientists publishing in science journals was produced by schools that perpetuate de facto social and class filters. That means many of those in the higher echelons of climate academia have limited interactions with Black and other people of color, he said.

And that not only “concentrates a culture, it concentrates a view, and it amplifies a segregated community of climate scientists,” said Morris, who is a professor of chemistry and environmental sciences at Arizona State University.

Such a narrow demographic limits scientists’ perspectives, and consequently their output. Research in critical areas has largely failed to address concerns of the larger population, Morris said. When scientists overlook communities in nations either rich and poor—when they don't monitor air and water continuously and don't watch storm patterns—they can't help save lives and boost livelihoods. In this way, racism also generates an incomplete picture of the world that can limit policymaking, leaving many millions of people facing disproportionate harm from growing threats.

Morris has been working to right these wrongs. He’s been encouraging students of color to enter a field that needs them—he was a founding director of the atmospheric sciences program at Howard University, and also started a networking group for minority students called the Colour of Weather. And last year, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Morris published a call to action signed by nine other scientists to push the geosciences to break structures that keep people of color from succeeding.

“Black faculty are subject to biased reviews of job applications, grant proposals, and promotion packages, as well as the refusal to mentor them in an appropriate capacity,’’ Morris wrote.

Calls to address racism are echoing around the profession. Susan Lozier, president of the American Geophysical Union, a large professional organization for Earth and space sciences, said that a change in mindset is needed. “The ivory tower is very hierarchical, there are so many layers that need to be unpacked,” she said.

Lozier said part of AGU’s new strategic plan is to connect scientists more with local communities and take on a “solutions-based” approach to science that would include global warming’s impacts, environmental justice and geohealth, which involves examining the effects of climate change on health.

Federal science institutions are taking steps to address disparities, especially since President Joe Biden’s first-day executive order elevating racial equality throughout the federal workforce and programs. The National Science Foundation said it formed a racial equity task force in November to help identify potential barriers to equitable access. NOAA said it created a “talent acquisition” unit to help market job opportunities within minority communities, and also is working on a similar initiative to boost senior executive recruitment next year.

And last year, NASA started a Justice, Equity Diversity and Inclusion Group within its Earth Science unit. It’s helping NASA work with historically Black colleges and universities on Earth-observation projects, which measure things like aerosols and precipitation. The group is also testing a new reviewing system to help root out implicit bias in selecting research projects. “Diverse people ask different questions and science is all about asking good questions,” said Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth Science group.

Diversity efforts are commendable, but they must break systemic obstacles for underrepresented students instead of focusing on building awareness about the benefits of it, said Gerald Torres, a professor of law and environmental justice at Yale University. “We have to be skeptical and make sure that these efforts aren't just a current fashionable policy position,” he said. “Durable diversity means structural change. Ideological change will then follow.”

Hurricane Katrina killed at least 1,200 people when it struck Louisiana in August 2005, causing more than $108 billion in damage. Morris said he was asked in its aftermath why residents of New Orleans and other high-risk areas didn’t leave town to escape disaster. He had to explain that many people already living in a vulnerable condition couldn’t leave.

White colleagues sometimes reveal their biases through naive questions, Morris recalled, and hurricanes are only the most extreme examples. Black and other marginalized populations have disproportionately suffered the consequences of old and new environmental hazards, be it so-called urban heat island effects—areas made hotter by buildings and roads retaining heat—in Chicago, St. Louis, or New York City, or hurricane-prone communities along the Gulf Coast and the Carolinas. A public-health study published in April concluded that people of color across all income levels and settings in the U.S. face harm from small-particle air pollution at a scale even greater than was previously understood. This week, researchers found that, in all but six out of 175 U.S. cities, people of color live in census tracts that are more susceptible to urban heat-island effects than non-Hispanic White people do.

The problem is also visible through a glance at what parts of the world are most saturated with scientific monitoring infrastructure: The temperate band that includes North America and Europe. While satellites have made progress in monitoring weather and dust storms of West Africa, there is still a legacy of neglect that hamstring African countries from understanding their weather.

“Africa is still the Dark Continent, to a large extent,” Morris said. “There’s been a hyper-focus on areas that are fundamentally more important to the scientists who were studying the problem.” Deeper collaboration between scientists in Africa and in rich nations would generate better data that strengthen climate models projecting future change.

To Gregory Jenkins, a professor of meteorology, atmospheric science, geography, and African studies at Penn State University, it’s become clear that writing journal articles for a narrow audience alone isn’t enough.

During the dusty and wet seasons in West Africa, “my phone will just go crazy,” Jenkins, 58, said, with calls from friends and colleagues seeking information that they can’t get elsewhere. Since October, he’s met Sundays on video conference with about 30 scientists from Nigeria, Senegal, Cabo Verde, and Angola to share forecasts as well as the effects of air pollution.

It’s that kind of commitment to helping people in areas without scientific infrastructure that university faculties should embrace, Jenkins said, as a way to make the academy more responsive to human need.

Jenkins’s trans-Atlantic collaborations are a contrast to the U.S., where he is tired of meeting after meeting where there’s only one Black person. “You just want to get out of there because it doesn’t feel normal,” he said. “I should not be the only one in here. Don’t tell me I’m the smartest person. I don’t believe you. Other people have been locked out of this system.”

Students of color are underrepresented in climate science in part because few have mentors, said J. Marshall Shepherd, a professor of geography and atmospheric sciences at the University of Georgia. More schools need to teach climate science and provide mentors throughout education, he said.

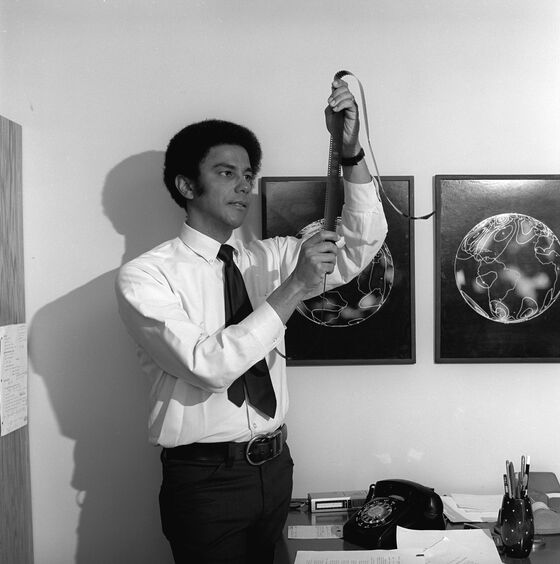

Climate scientist Everette Joseph likes to share the moment decades ago when he first saw Warren Washington, a man who he’d previously known only from a byline on research papers. Joseph had spent years reading works by Washington who, back in the 1960s, developed models that laid the groundwork for understanding climate change today.

It was at an event featuring top climate modelers that Joseph attended in the early 1990s, when Washington was introduced to the audience. Joseph looked up at him, and thought “Oh. My. God.”

“He looked like me!” said Joseph, director of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, a major U.S. climate research hub that trains undergraduates from historically underrepresented communities every summer. “I was really stunned.”

Washington rose from designing some of the earliest atmospheric models, in the 1960s, to advising five presidents and earning the National Medal of Science in 2010. He was the second Black student to earn a meteorology PhD in the U.S. Later, a national champion for recruiting people of color into the profession, Washington, 84, knows its history as well as anyone. “I just try to ignore those kinds of very negative experiences,” he said. As he helped jump-start climate science, he also worked on ways to open the profession to Black people, speaking at Southern schools and pressing key organizations to change. “Everyone recognized very early on that there was a lack of diversity,” he said.

Like Joseph, Jenkins at Penn State counts Washington as his mentor. So does Shepherd at the University of Georgia.

Shepherd, 51, was elected to the National Academy of Sciences this year. He’s spent a good part of his career helping younger Black scientists find their way. But he bemoans how scholarships aimed at turning students from marginalized groups into climate scientists often come too late. They need to be targeted at school age, he said.

And he said the role can often feel tokenized. “When people look at your scientific career, a lot of Black scholars get typecast inadvertently as mentors and outreach people,” he said. “And they get short-circuited by that typecast, so they don’t ever evolve to high-level scientists.”

ASU’s Morris says power structures need to change. “It’s all the gatekeepers, the distinguished professors, the deans, that’s where the entrenched attitudes are,” he said. “And that’s why policies addressing class and inequity are important. That’s how you disrupt entrenched power. That’s where you’ll get the biggest bang for the buck.”

How do you change policy? Some of these researchers are applying their training to figure it out. A National Science Foundation-funded initiative ginned up in the final months of 2020 may recommend some ways.

Vashan Wright, a 31-year-old incoming assistant professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, started building the Unlearning Racism in Geoscience (URGE) program last summer and fall while working at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. It’s an interactive workshop created to generate concrete policies that can address the field’s lack of diversity and its consequences on scientists of color. URGE drew several thousand participants from the geosciences by the end of its 16-week curriculum this month.

Over the next few months, participants in the virtual program will hone policy proposals that they’ll take back to their departments or institutions and present as ways to change destructive practices. These proposals might include anything from mandatory antiracism training, to funding or staffing consequences for repeat offenders of racist bias or harassment, to collaboration guidelines for conducting fieldwork with local communities. And after that, Wright and colleagues will assess how the program did. That analysis is central to understanding what sets URGE apart—and why it may be replicable to the private sector. URGE is harnessing the best of science—inquiry—to identify policies that limit the worst of science: racism. “Without each piece, it would have been just another ‘book club’ full of people talking with no action,” said Onjalé Scott Price, chief operating officer of Mizar Imaging, and a member of the URGE team.

Can small-scale action lead to broader systemic change? Wright’s research may offer hope.

“I am a geophysicist,” he said. He started out in geology in college, but wanted to attack the world with deeper quantitative skills. “I wanted to study how small-scale processes lead to big, observable Earth processes.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.