A Warning Sign on Italy's Euro Membership

A Warning Sign on Italy's Euro Membership

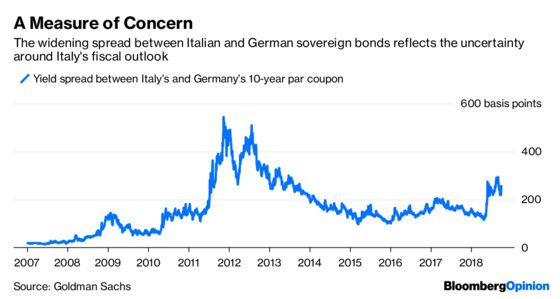

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Italian government bond yields hit four-year highs this week, which is hardly surprising after the country’s unexpected proposal for a bigger-than-expected budget deficit. At the 10-year maturity, the widening spread to German bonds shows the anxiety around the fiscal outlook:

But we mustn’t forget the other investor concern expressed in the spread: That of the government’s ambivalence toward Italy’s euro membership and its potential “Plan B” to reintroduce the Lira. It would certainly be useful to assess how markets are pricing this risk, especially given the possible contagion impact on other euro-zone countries – and the euro itself.

When looking at the spread, there’s obviously a lot of overlap between how it reflects the risk of a debt restructuring and that of a re-denomination of Italy’s currency. A sovereign default might very well create pressure to break away from the euro. So teasing them apart is challenging. But sovereign Credit Default Swaps (CDSs), an insurance policy on bonds being paid out in full, provide some clues on the relative importance of the two threats. They indicate that parts of the financial markets are becoming more eager to protect themselves against a so-called “Ital-exit.”

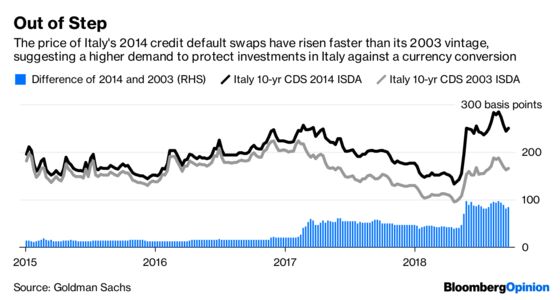

The 2003 vintage of sovereign CDS contracts promises to pay back the face value of government bonds in the event of a debt restructuring. The 2014 version offers additional protection against the risk that the defaulted bonds may also be converted into a currency other than the euro. So the price difference between 2014 and 2003 CDSs with the same maturity shows the extra insurance premium investors are willing to pay for protection against a currency re-denomination.

The price of the two CDS vintages usually moves in lockstep. After all, they both cover the same risk of default. Since last April, though, the price of the 2014 CDSs has risen faster than its counterpart (see the chart below,) suggesting a higher demand to protect Italian investments against a currency conversion. Indeed, about half the increase in the cost of insuring exposure to Italian government bonds in recent months appears associated with the risk of a return to the Lira.

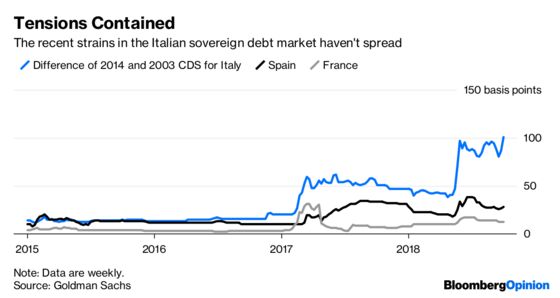

It’s not the first time that “convertibility risk” has resurfaced in the euro area since the 2011-2012 sovereign debt crisis. Just before the French presidential elections in 2017, investors worried that a Marine Le Pen victory would call into question the country’s monetary union membership. The sovereign CDS market reflected this concern, with the price differential widening between 2014 and 2003 CDS vintages on French debt, a similar phenomenon to the one seen in Italy recently. That, in turn, was reflected in bond yields across the entire single currency area, particularly in the southern European countries.

This time, though, the Italian tensions have had limited spillovers so far. Yields on 10-year Spanish government bonds, for example, are close to the same levels as they were in the first quarter at about 1.5 percent. Indeed, the pricing of different CDS vintages in Spain and other European Monetary Union countries – shown in the chart below – suggests a euro breakup is not considered a significant threat outside Italy.

Supporting this view, Goldman Sachs economists have constructed an index of systemic risk in the euro zone based on how sovereign bonds have moved at certain times. The risk index, which ranges from zero to 100, stands at about 9. In the run-up to the second round of the French election, it was in the low 20s.

So is there a rational reason for why Italy is not creating more shockwaves abroad, or is the market being too complacent?

One simple explanation could be that sovereign CDSs aren’t all that representative of concerns among the broader investor community. The weekly notional volume of sovereign CDSs on Italy, cleared on the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation, is about 2 billion euros. That compares to roughly 20 billion euros of Italian bonds traded on the MTS electronic platform every week.

There are technical differences too between the 2003 and 2014 CDS vintages, which might make the 2014 instruments more attractive in times of stress. Reading too much into CDS pricing could, admittedly, be a risky proposition in itself.

And it’s true that the political conditions prevailing in Italy are unlikely to be replicable in other euro area countries, which are for now governed by moderate, pro-European forces. Moreover, there are financial “fire-breakers” that didn’t exist during the 2011-12 crisis, which would offer precautionary credit lines and central bank bond purchases to a euro-zone country hit by the financial shockwaves originating from, say, a downgrade of Italian debt to “junk.”

Meanwhile, “Ital-exit” still ranks low as an issue among the country’s voters, who are absorbed by migration and income redistribution. So all in all, much of that increasing premium for Italian government bonds seems largely related to the fiscal stance, the confrontation with the rest of Europe and the specter of rating downgrades.

And yet it would be unwise to dismiss entirely what those CDSs tell us. Yes, there are technical factors that warn us against interpreting them too broadly, but that was also the case before the French election, when they offered a reliable guide about risks to the euro zone’s unity.

Should pressure on Italian bonds intensify and European institutions try to contain any spillover by isolating the country’s financial system, it’s far from certain whether public opinion there would turn against the government or Brussels. Accounting for 15 percent of the euro area’s GDP, and with more than $3 trillion of external liabilities, Italy remains a systemic fault line in global markets.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Francesco Garzarelli is an advisory director to Goldman Sachs International.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.