Silicon Valley Helped Kill Local News. Can Charity Bring It Back?

Silicon Valley Helped Kill Local News. Can Charity Bring It Back?

(Bloomberg) -- The City, a website covering local news in America’s biggest metropolis, debuted this month with a bank account some of its nonprofit peers could only dream of.

Backed by almost $10 million from philanthropies and individuals, the New York-based news organization has more than double the cash that nonprofit-pioneer the Texas Tribune had when it started 10 years ago.

Still, the City’s publisher is taking nothing for granted. A former investment banker, John Wotowicz is constantly looking for additional sources of funding. He’s planning to spend about $4 million this year, much of it on his 18 reporters. If the donations stop flowing, the City will run out of money by 2022.

“We have 2 ½ years of runway in the bank,” Wotowicz said recently in the City’s Manhattan newsroom. “That’s not 25 years of funding. Fundraising will continue to be a terrifically important part of our business.”

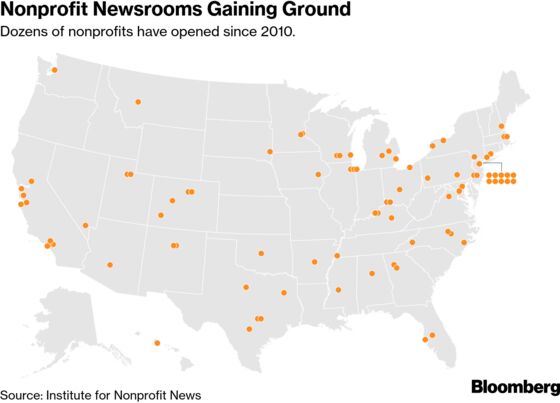

Such is life in nonprofit news—and perhaps a sign of things to come for American journalism in general—where the future is never guaranteed and the hustle for donors never stops. The City is one of about 200 nonprofit newsrooms nationwide whose 2,200 journalists try to make a living by greening so-called news deserts—large swaths of the country that have been left uncovered as one local paper after another dies.

Even New York and its brand-name newspapers, the New York Times and New York Daily News, have reduced local coverage over the years, a reality that opened the door for the City. But while Wotowicz hopes to achieve the financial security enjoyed by ProPublica or the Texas Tribune, many nonprofit newsrooms struggle to stay afloat, and some have been forced to merge or shut down.

“It’s like Indiana Jones outrunning the boulder,” Texas Tribune Chief Executive Officer Evan Smith said. “You have to focus on the business 24 hours a day, seven days a week, or you’ll get flattened.”

The Austin, Texas-based Tribune was one of the first nonprofits to spring up as America’s for-profit newspaper industry began to collapse in earnest. The idea of running a newsroom like a charity isn’t new. Some nonprofits, such as the Center for Investigative Reporting, date to the 1970s. But many arrived over the last decade, a period when newspapers shed almost half their employees, or 32,000 jobs, after readers and advertisers moved online.

The nonprofit model still has a problem, however. When it comes to raising money, there’s a disconnect between nonprofit journalism and the public. Many Americans don’t know there even is a local news crisis.

A recent Pew Research Center survey found that 71 percent of those polled believe their local media is doing well financially, while only 14 percent said they paid for local news access in the past year. Others have yet to conceive of journalism as a critical component of a free society, and may not think of a newsroom in the same way they do the Salvation Army or the American Red Cross. And then there are journalists, many of whom are uncomfortable asking for handouts.

“It’s difficult for journalists who spend their careers following the money to go, hat in hand, and say, ‘I’m a reporter. I’d like you to give me money,”’ said John Adams, founder of the nonprofit Montana Free Press. “It was something I wasn't accustomed to.”

A study published last summer by Duke University’s DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy found just how lacking the quantity and quality of local news is across America. Only 17 percent of stories presented by local outlets were based on events that actually occurred nearby, and more than half originated from media organizations based outside the community.

Alarmed by how the demise of local news threatens government accountability, philanthropies have been pouring money into possible solutions. Over the next five years, the Knight Foundation plans to double its investment in local news, to $300 million. Silicon Valley is opening its wallet, too—Laurene Powell Jobs, Craigslist founder Craig Newmark and EBay founder Pierre Omidyar have all contributed through their foundations to the American Journalism Project, which is raising money to fund as many as 35 local newsrooms.

Many of these donors have reached a sobering conclusion: In-depth reporting on such beats as education, the environment or local government will never be profitable and must adopt the National Public Radio model to exist. Even the for-profit Seattle Times is seeking donations from the community for investigative reporting.

“There’s an increasing awareness that the for-profit market is not going to supply journalism at the level we need it,” ProPublica President Richard Tofel said.

Ironically, it was Craigslist that long ago began the web’s siphoning of advertising dollars from newspapers, followed by Google and Facebook. Now these tech behemoths are dedicating hundreds of millions of dollars to help support local news.

Several nonprofit newsrooms have become sustainable. ProPublica, an investigative news site with about 120 employees, generated $30.2 million in revenue in 2018, up from $28.3 million the year before. Founded in 2008, it’s amassed $25.5 million in reserves, nearing its goal of setting aside a full year of expenses.

The Texas Tribune generated $9.1 million in revenue last year, up from $7.7 million in 2018. Of its projected $10.1 million in revenue this year, the site expects to get about $2 million from major donors, close to $2 million from corporate sponsors and about $2 million from events like its annual festival, Smith said. That helps pay for the largest reporting staff covering any state capital in the country.

Every month, two or three people reach out for advice on how to start a nonprofit newsroom, Smith said. “We try to save people elsewhere in the country from making the mistakes we made,” he said. “There’s a pay-it-forward aspect of this.”

But while ProPublica and the Texas Tribune have been success stories, many smaller outlets are scrounging for funds. EcoRI News, started in Providence, Rhode Island, in 2009, reports on environmental and social justice issues. With revenue last year of more than $200,000, it has just three employees and a desk at a co-working space.

EcoRI has funded its journalism in expected ways—from advertisers, events and grants. But it’s also been forced to get creative, albeit in ways that fit with its mission. In addition to accepting donations from a local church and choir group, the website has made money by collecting food scraps and Halloween pumpkins for composting, turkey carcasses to feed pigs, and Christmas trees to make mulch.

About 13,000 people subscribe to EcoRI’s email list, but only a small percentage of them donate, said Joanna Detz, the site’s executive director. The hardest part of nonprofit journalism is “getting people to pay for a product that they get for free,” said Detz, who started the site with her husband, Frank Carini, after he left his job as city editor of the Newport Daily News.

As hard as the struggle is for some, failure remains relatively rare so far. During the last four years, out of more than 200 nonprofits, only about 10 have shut down, said Sue Cross, CEO of the Institute for Nonprofit News, which provides support for newsrooms. Since the nonprofit model took hold, though, outlets such as the Raleigh Public Record, Oakland Local and the Chicago News Cooperative have shuttered or suspended operations. Others have been forced to merge with public media stations.

Most of those that do fail, nonprofit journalists said, do so because their founders don’t start with enough funding or lack business experience.

Adams began the Montana Free Press in 2016 after being laid off as a statehouse reporter for the Great Falls Tribune, which is owned by newspaper giant Gannett Co. He stopped publishing a few months later because he struggled to collect donations.

“I had no real experience raising money and was in over my head,” Adams said. “I was paying expenses with credit cards. I got to a point where I was financially broke.”

Adams relaunched the site in late 2017. After he was featured in the PBS documentary “Dark Money,” which used Montana to tell the story of how corporate money controls state politics, the site’s financial situation improved. “The donations started pouring in,” Adams said. Recently, he even hired a second reporter. But not every nonprofit news site can star in a blockbuster documentary.

The City launched April 3 at an especially dark moment for local journalism in New York: Over the past two years, the Village Voice closed after decades of journalistic decline, and the iconic Daily News fired half of its editorial staff. Even such up-and-comers as DNAinfo, a neighborhood news website, shut down.

During a midday visit earlier this month, the City’s newsroom was quiet. The walls were bare except for a few banners depicting the website’s logo: a pigeon. (A contest to name the bird generated over 4,000 entries. The winner was Nellie, after the pioneering journalist Nellie Bly.)

Most staffers were out covering beats that include local transportation, education and housing. The site that day featured articles on questionable spending by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, expensive park bathrooms and foreign students facing possible deportation after their school shut down.

Many reporters at the City come from for-profit news organizations, including the Daily News or NY1, a local cable news channel. Their salaries, Wotowicz said, are “very competitive.” Still, as a reminder that the website is a nonprofit, the staff recently held a meeting to decide how to decorate the newsroom. Their budget? Less than $1,000.

So far, the site has about 400 members who’ve donated between $1 and $2,500. Over the next two years, Wotowicz’s goals are to extend his reserves to last through at least 2024 and for its revenue to come from a wider variety of sources, including corporations.

New York can be a cutthroat place for journalists who battle for scoops, but Wotowicz, who has served on the boards of NPR and the Texas Tribune, said he hopes the City would see more competition, not less.

“This industry is in a post-competitive world,” he said. “The number of journalists on the street could increase fivefold and it still wouldn’t be enough to cover all that’s going on.”

--With assistance from Dave Merrill.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at drovella@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.