Big Money, No Debt: The Blunt New Pitch for Blue-Collar Workers

Big Money, No Debt: The Blunt New Pitch for Blue-Collar Workers

(Bloomberg) -- Like other college prep schools, Bishop McLaughlin Catholic High School north of Tampa, Florida, touts its 100 percent college acceptance rate to burnish its image and recruit students.

This year it could fall short of that mark for the first time in a while. Instead of shooting for the University of Florida or another four-year college, graduating senior Cassian O’Neill is leaning toward installing water heaters and fixing leaky toilets as a plumber.

“I don’t want to sit at a desk all day and work on a computer,” said Cassian, 19. "I want to do more hands-on work, so I thought the best way to do that was being a plumber or an electrician or a welder. The amount of money plumbers are making is definitely decent and it can always go up because so few people know how to do that work.”

Indeed, the 40 plumbers at Superior Plumbing in Atlanta earn around $90,000 in wages and commissions -- about 70 percent higher than the region’s average income. Owner Jay Cunningham figures he could immediately fill 20 more plumbing jobs if he could find people with the right set of skills and a presentable appearance and demeanor. He blames the talent shortage on parental bias for college over the trades.

"We probably need to do a better job hammering in how much debt you’re going to have going to college," said Niel Dawson, who runs apprentice and training programs for Independent Electrical Contractors in Georgia. "From day one you’re earning money in an apprenticeship program."

Six-Figure Mechanics

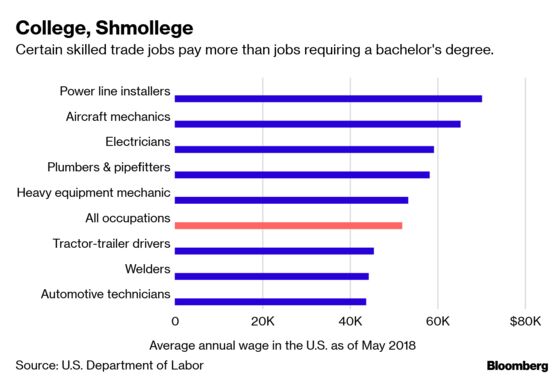

The 3.8 percent U.S. unemployment rate has exacerbated a skilled labor shortage that had been building for years. To turn the tide, American’s blue-collar industries are adopting a blunter recruiting approach by touting how new entrants can earn more than some college graduates, without incurring tens of thousands of debt. Specialized jobs including aircraft mechanics and heavy- equipment technicians can surpass $100,000, and industry groups and states including Michigan and Georgia are incorporating that into their advertising campaigns.

Georgia recently spent $3 million on a campaign to push its technical colleges and is touting its tuition-free grant program for 17 high-demand jobs, including commercial truck driving, electrical linemen and diesel equipment technology, said Matt Arthur, commissioner of Georgia’s Technical College System.

In Michigan, the state Department of Talent and Economic Development is behind a campaign called Going Pro that tries to create a buzz around the professional trades. Front and center on the campaign’s web page, www.going-pro.com, is a list of career fields and how much they pay -- mentioned even before a description of what each job does.

Electrical power-line installers and repairers earn $77,000, the site says. Plumbers and pipefitters earn $65,000.

“The biggest question that we get is, ‘How much money can we make?’,” said Sammie Lukaskiewicz, the agency’s deputy director of marketing and strategy.

Signing Bonuses

Trash hauler Waste Management Inc. offers $7,000 signing bonuses for certain mechanic jobs, and some competitors are offering up to $15,000, said Chief Human Resources Officer Tamla Oates-Forney. The company’s drivers meanwhile will earn $50,000 to $75,000 a year, she said.

Waste Management is also trying more creative ways to plug hard-to-fill jobs, including testing a new program to let workers steer landfill bulldozers remotely.

“You don’t have to be out at a sweaty, stinky landfill. You can be in a very pristine, pleasant environment,” Oates-Forney said. “It’s going to be more appealing, and we will be able to recruit veterans and also women who might never have thought about being in this type of industry.”

Major automotive players including Nissan North America, Manheim and Interstate Batteries are pushing young people to become auto technicians through an advocacy group called the TechForce Foundation. It’s urging repair shops to talk up their potential wages as much as possible and go way beyond traditional high school career fairs.

"You gotta get out there and start talking with them in middle school,” said TechForce director of national initiatives Greg Settle.

To be sure, a bachelor’s degree generally is more lucrative in the long run than a middle-skill job that requires some post-secondary education short of a four-year degree. Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce has studied the growth of what it calls “good jobs” -- those paying at least $35,000 or $45,000 depending on someone’s age -- over time and among people with different education levels.

Good jobs requiring bachelor’s degrees doubled between 1991 and 2016, while middle-skills jobs including many trades grew a more modest 29 percent, the center found. Good jobs requiring only a high school degree fell by 12 percent.

Tuition-Free

Soaring college debt, though, could tip the scales in favor of trade schools for at least some students. Student debt loads reached almost $29,000 on average nationally in 2017, with Connecticut students carrying more than $38,000 in debt, according to to the Institute for College Access and Success. While some trade certificate programs can cost as much as $45,000, many are covered in part by employers and others, like Georgia’s programs, are tuition-free.

Eight years ago, Hayden Bramlett was suffering through business courses at Valdosta State University in south Georgia. “It was like watching paint dry,” he says.

Today, the 28-year-old is finishing up a four-year electrician training program at an Independent Electrical Contractors campus in Atlanta. Meanwhile, he’s working for one of the Atlanta area’s bigger electrical, plumbing and air conditioning companies, earning more than $100,000 some years, he says.

If one is willing to work, the demand for electricians “way outweighs the people we have in this trade," Bramlett said. "I never knew this was an option. I was steered toward college. It feels good to know I could walk out the door and get a job.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Michael Sasso in Atlanta at msasso9@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anita Sharpe at asharpe6@bloomberg.net, Steve Matthews

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.