The ECB Proves Central Bankers Are Bad Capitalists

The ECB Proves Central Bankers Are Bad Capitalists

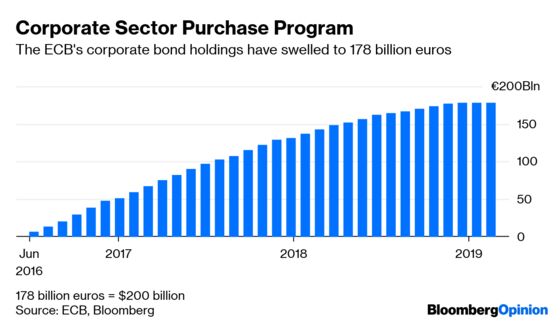

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The global synchronized economy recovery has turned into a global synchronized economic downturn. The outlook seems to be getting bleaker by the day, and major central banks are hinting that they may need to keep monetary policies loose. The European Central Bank has even suggested that it could start buying corporate bonds again. Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that because it’s becoming evident that central bankers make for bad capitalists.

Consider Germany’s AG Bayer, which agreed to buy Monsanto in May 2016 for $66 billion in what was then the largest all cash merger ever announced. The deal was controversial from the start as Bayer was going to need to raise billions of dollars. Traditionally, this means a company must go on a road show and explain its plan in great detail. Without evidence of a credible plan, capitalists will not part with their money.

But not the ECB. It just so happened that in June 2016 the central bank began a new effort to stimulating the region’s economy by purchasing corporate bonds under an initiative dubbed Corporate Securities Purchase Program, or CSPP. So how did the ECB decide which corporate bonds to buy? The CSPP set up the following simple rules to qualify:

- Incorporated in the euro zone and denominated in euros

- Non-financial, including any parent company (the ECB was already in too deep with the banks)

- Investment grade with a maturity between 6 months and 31 years

- No asset backed or structured securities

Nowhere in these rules were considerations such as coverage ratios, debt to equity percentages, use of cash, or management plans. The ECB left those issues to the credit rating companies. As long as a company kept its investment-grade rating, that was good enough for the ECB. The last time investors delegated investment decisions to ratings firms in this manner was mortgage securities in the early to mid- 2000s. This was before housing collapsed, leading to large defaults on mortgage securities and ushering in the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Lesson not learned at the ECB.

Bayer’s Monsanto purchase has been nothing but problematic. The company said last week lost a second trial over claims the weedkiller Roundup that came with the Monsanto deal causes cancer. Its shares have fallen to their lowest since 2012, although it retains an investment-grade rating for now.

The ECB has been very secretive about the CSPP program. It only publishes a list of company debt securities it holds, but not amounts. At last count there are 1,192 corporate issues totaling 178 billion euros ($200 billion). Bayer is on the list, but the amount of debt the ECB bought to finance the Monsanto deal is unknown.

The ECB should have known better. In September 2015, before the CSPP began, the ECB was buying car loans, asset-backed debt and securitized loans. This included the benchmark issuer of Volkswagen, which became embroiled in rigged emission tests in the U.S. for its diesel cars. How important was the ECB to Volkswagen? When that scandal hit, the ECB announced that it would suspend purchases of Volkswagen debt securities. The move hurt the company’s ability to raise money.

Or in January 2018 when the ECB was forced to sell its Steinhoff International Holdings NV debt after the company was downgraded to junk following accounting irregularities. The ECB’s cheap money, no questions ask program also financed, maybe supported, other troubled companies such as Arkema SA, Proximus SADP and Glencore Plc.

What does the ECB say about all of this? The central bank conducted a top down macro study last year that concluded:

Reassuringly, evidence of adverse side effects on corporate financing and market functioning as a result of the CSPP is rather scarce. In particular, the smooth implementation of the program, underpinned by the flexible pace of Eurosystem purchases and its adaptability to dynamics in the primary market, has safeguarded corporate bond market functioning and liquidity conditions. Overall, these findings back up the assessment of a successful implementation of the program under changing market conditions without having a distortive market impact.

In other words, the ECB is falling into the trap of mistaking brains with a bull market. Buying bonds when things are good will show good results. The question is, are they creating easy money distortions so companies can engage is questionable behavior? The ongoing saga of Bayer’s purchase of Monsanto thanks to the ECB suggests policy makers need to look deeper at the true costs of this program. If they do, they might not like what they see.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jim Bianco is the President and founder of Bianco Research, a provider of data-driven insights into the global economy and financial markets. He may have a stake in the areas he writes about.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.