One Risky Birth Shows How Venezuela’s Diaspora Strains Its Neighbors

One Risky Birth Shows How Venezuela’s Diaspora Strains Its Neighbors

(Bloomberg) -- Days before her baby was due, Raquel Reyes began bleeding. The hospital in La Fria, Venezuela, lacked staff and incubators and sent the 18-year-old away. She tried Venezuela’s parallel Cuban-run medical service, founded when oil money was plentiful, but the building was abandoned and without electricity.

“There wasn’t even one doctor,” she said. “Everything was dark, and at that moment there was a blackout, so we decided to go to Cucuta.”

So began a trek to the Colombian border town to bear her first child. Afflicted by abdominal cramps and starting to panic, Reyes passed along dirt tracks controlled by armed gangs, then crossed a river in a small wooden boat, eventually reaching Cucuta and the maternity ward.

In hospitals, classrooms and migrant shelters, Venezuela’s neighbors are picking up the tab for the nation’s economic implosion. Millions have fled the regime of President Nicolas Maduro in the largest mass emigration in modern Latin American history. About 200 people an hour leave the country, and, if things don’t change soon, the exodus soon will exceed the 6.3 million refugees created by the Syrian civil war.

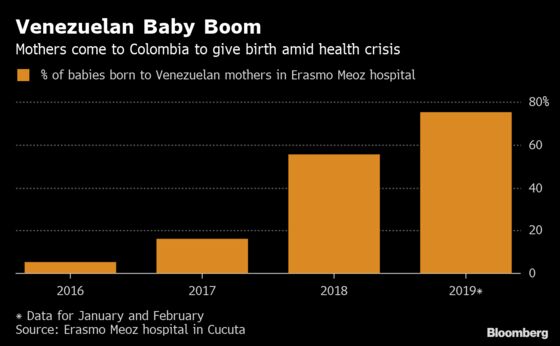

In Cucuta, 75 percent of newborns in Erasmo Meoz hospital during the first two months of this year were born to Venezuelans. That’s up from 5 percent in 2016, according to doctor Norberto Garcia, head of its maternity unit. The hospital’s debt has ballooned to about $14 million, from $1 million before the crisis, he said.

“We see many more Venezuelans arriving every day, and we have to spend resources, medicines and personnel, but we’re not getting the money we need to maintain the institution,” Garcia said.

The Venezuelan diaspora may swell to about 8 million by the end of next year, from 3.4 million now, according to the Organization of American States. That’s creating a new underclass across South America: From Panama City to Buenos Aires, desperate Venezuelans hawk candies at traffic lights, sell their bodies on the streets, pick coffee and deliver packages. Some have even joined Colombia’s Marxist guerrillas, who fill a vacuum of authority in the lawless border region.

“The situation is already overwhelming the Colombian government,” said Sergio Guzman, director of Colombia Risk Analysis, a Bogota-based consultant. “The hospitals in Cucuta have already spent their budgets for the year and then some.”

Even Chile, the region’s richest economy, is feeling the strain. A year ago, when migration was much lower, the government estimated the cost of health care and education for migrants at more than $260 million per year. President Sebastian Pinera’s administration tightened visa rules, but this slowed the flow of people only temporarily.

Chile, Ecuador and Argentina host a total of 620,000 Venezuelans. Peru has 700,000. But Colombia, which shares a loosely controlled 1,400-mile (2,250-kilometer) border with Venezuela, bears the brunt.

At least 1.2 million migrants and refugees have arrived there, and thousands more come every day, according to a report last month by the Organization of American States. The United Nations last month set up what appeared to be the first camp in the border region—technically it’s an “Integrated Assistance Center”—to provide food and shelter for Venezuelans who’d been living rough near the crossing at the town of Maicao.

As well as providing services for migrants, Colombia finds itself helping tens of thousands of Venezuelans who cross the border when they have a medical emergency. Every weekday at dawn, thousands of children cross to attend Colombian schools, because the education system has collapsed, too.

It all costs money. Colombia last week increased deficit targets, allowing it to take on debt for services Venezuela can no longer afford. In truth, Colombia can’t afford them either. Credit-rating companies already were breathing down its neck, and Bank of America wrote in a March report that the nation may face a downgrade as soon as this month.

Health care is among the most expensive services. In Venezuela, malnutrition has become endemic, common medicines are unavailable at any price and curable diseases nurtured in the tropics are beginning to spread.

The Colombian government has provided more than 900,000 vaccines to Venezuelans in the past year and a half, according to the Ministry of Health, mostly to children under age 5. In the government’s worst-case scenario, the number of migrants in Colombia will increase by multiples, and health officials fear the spread of malaria and tuberculosis, aggravated by the lack of communication with authorities on the other side of the border.

Many of those fleeing are young and, like Reyes, of childbearing age. As recently as 2012, a baby had a better chance of surviving in a Venezuelan hospital. By 2017, its chances were twice as good in Colombia, according to the World Bank. While infant mortality jumped 76 percent in Venezuela during that time, to 26 per 1,000 live births, in Colombia it’s fallen to 13 per 1,000 live births.

Venezuelan pregnancies are risky due to a lack of prenatal care and malnutrition, Garcia said. Five of the six mothers who died during childbirth in the hospital last year were Venezuelans.

Babies born in Colombia don’t automatically become citizens. But many mothers hope to stay long enough to make their children eligible for Colombian nationality, affording a better chance in life—reversing the situation that applied for most of history, when migrants would flee poor, war-torn Colombia for peaceful, oil-rich Venezuela.

Reyes’s son, Jahaziel, was born March 26, weighing six pounds. The ward was clean and well lit. The baby had healthy red-mottled cheeks and wore a onesie covered with baseballs. Raquel Reyes returned to Venezuela three days later.

“They took great care of me and gave my little boy all his vaccines,” she said. “Practically all their patients are Venezuelan, and may God bless them for all the help they’re giving us.”

Colombia didn’t charge her a single peso.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephen Merelman at smerelman@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.