Tech IPOs Aren’t the Milestones They Once Were

Tech IPOs Aren’t the Milestones They Once Were

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Later Thursday, Lyft Inc. will most likely sell its first batch of stock as a public company. It’s a milestone for the on-demand transportation company, and it will officially kick off the great tech unicorn IPO barrage of 2019.

Depending on your perspective, this flood is either validation for the class of companies created since smartphones and cloud computing made new technology businesses possible or a sign that startups are rushing to catch the last innings of the decade-long U.S. stock market expansion.

All indications are that Lyft’s IPO will go swimmingly. On Wednesday, the company raised the price range for the public share sale, suggesting healthy investor demand. (Or it’s a sign that bankers know to lowball the initial price range so they can increase it later.) At the high point of Lyft’s estimated IPO share price, the company would have a market value of more than $20 billion, excluding the value of equity held by employees and others.

Right now, I think yes. Rock-bottom U.S. interest rates are not likely to go up soon, which makes investors hunt for higher risk-and-reward assets, including tech IPOs. After some wobbles last year, U.S. stock indexes have been on a tear in 2019. These are ideal conditions for companies with fast growth but typically ugly losses to pitch themselves. Lyft’s $911 million loss in 2018 sets a record for the widest loss of a U.S. startup in the year before an IPO. Uber will likely eclipse that record soon.

There will be a breaking point when investors balk at one or more of these IPOs, but I can’t predict what it will be or when.

But no matter how Lyft and the others do when they go public, changes in capital markets and technology startups in the decade after the financial crisis have made IPOs less momentous than they once were.

The defining characteristic of the superstar startups created after 2008 is that they have access to far more capital than prior generations — the scale of cash that used to be available only to public companies. That allowed private companies to think big and grow fast. Uber, Lyft, WeWork Cos. and many others could not have existed in their current form at any other time.

They don’t need IPOs to fund themselves or to reward investors. In fact, as the money going into young firms has been turbocharged, IPOs are no longer the outlandish investor windfalls of popular imagination.

Lyft has raised about $5 billion to fund its multiple business shifts and expansion. The IPO valuation looks to be about five times the amount investors had committed. Uber will go public at maybe five or six times its $20 billion in capital raised. Compare that with Facebook Inc., whose first-day public valuation was about 50 times the $2 billion in investments before its IPO. Google’s IPO valuation was more than 600 times the money raised in private funding rounds.

That’s not to say young tech companies aren’t worth the risk. Early investors in Lyft, for example, are receiving huge returns. Venture-capital firm Floodgate Fund LP bought shares of Lyft starting in 2010 at a $5 million valuation, the firm’s partners told Bloomberg Television, while Lyft’s IPO valuation will be about 4,000 times that figure.

Later private investors such as the mutual fund giant Fidelity Investments are thrilled to double their money on investments made in the last year or two. That’s a great outcome for Fidelity and one sign of the change in startup financing: It’s no longer confined to a tiny number of specialist investment firms in Silicon Valley.

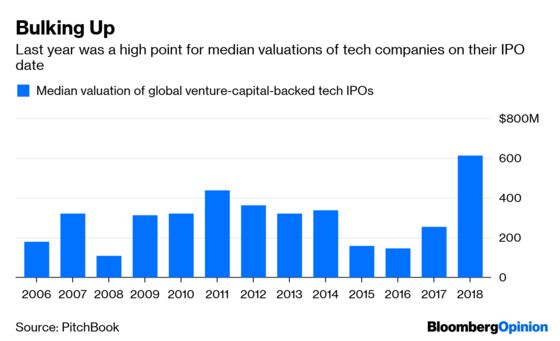

That increasing supply of investors means more cash is available to young companies to expand and stay private until they’re older and bigger and have larger market values — although not necessarily profits.

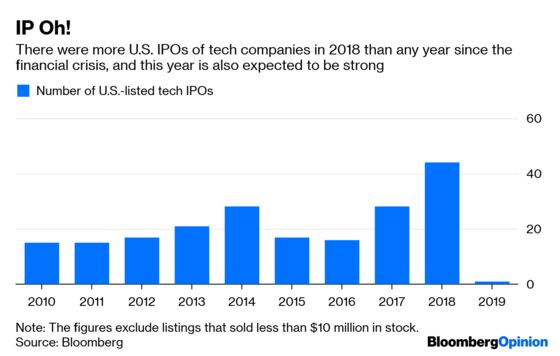

The median age of tech companies going public was 12 years in 2018 compared with four years in 1999, according to University of Florida finance professor Jay Ritter. Median valuations as companies go public are increasing too, PitchBook figures show. But about 16 percent of last year’s tech IPO class was profitable in the year before an IPO — the lowest share since the dot-com bubble.

Overall the changes in what it means to be a “startup” are making the IPO less of an occasion. It’s more like a company is choosing to enter a slightly different phase in which it may still be unprofitable for a while but is committed to self-funding, as my colleague Matt Levine put it on Wednesday.

IPOs do still matter, particularly to investors and as symbols of a commitment to maturation. We just need to think of them as less of a Big Bang and more of a modest transition.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.