’08 Autopsies Ask the Wrong Questions

’08 Autopsies Ask the Wrong Questions

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bloomberg Opinion marks the 10th anniversary of Lehman’s bankruptcy with a collection of columns from around the world. Read more.

It’s been a decade since the collapse of Lehman Brothers Inc. triggered the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, and many market participants are still asking the wrong questions about that once-in-a-lifetime (hopefully) event.

There are two main schools of thought explaining financial crashes. One looks for reasons why asset prices got so high in the first place, and sees the bust as a painful but necessary correction. The other asks why the fallout was so bad after prices fell. Both approaches miss the important question: What happened between the peak and the trough?

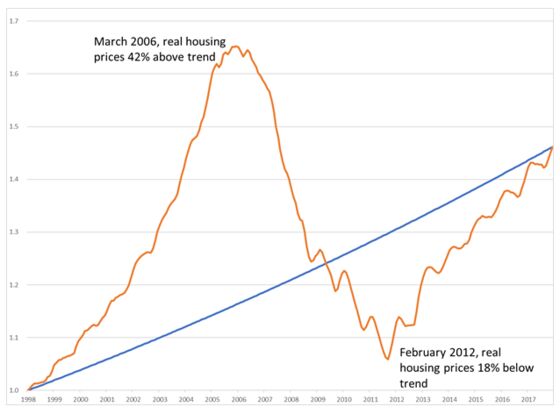

The graph below shows real national housing prices over the last 20 years, with the blue line representing the trend of 1.9 percent increases per year. Prices peaked in March 2006 at 42 percent above the trend. Many explanations have been offered. Between 2006 and 2012, prices didn’t just return to trend, they plunged 18 percent below it, and took much of the financial system and the economy with them. Some blame too little or too much stimulus, Wall Street greed or regulatory mismanagement, among other things.

As someone who lived through the crisis as a Wall Street risk manager, I have a different view. The crisis constituents were evident early in 2006. By then, eight years of rapid increases in real housing prices had stalled at the same time many financial products tied to the real estate market were predicated on a continuing increase in such prices. Subprime mortgage delinquency rates soared. More worrisome, an unprecedented number of prime and subprime mortgages were not even making their first payments.

The number of mortgage fraud cases investigated by the FBI had almost doubled between 2003 and 2006 to 818, the Associated Press reported in early 2007, making the category one of the fastest growing types of white-collar crime in the U.S. at the time. Commercial real estate deals were running into cash flow problems, and already highly levered companies were borrowing ever more money at increasingly looser terms, not to buy assets, but to pay interest on existing debt and dividends to private equity owners.

It was well known which sectors of the economy were troubled, but not how big the crisis would get. There are always problematic sectors in finance, and the financial system cannot shut down over hypothetical scenarios. Early 2006 had more than the average amount of worries, but not an historically extreme level.

Still, you might expect that precautions were taken in the known problem areas: tightening mortgage lending standards and fighting fraud, reducing the issuance of vulnerable securities, cutting financial institution leverage, lowering interest rates to protect banks and the economy, increasing loss reserves, etc. Perhaps not in early 2006, but certainly sometime over the next two years as things worsened dramatically.

Here’s what happened in the two years after the problems surfaced:

• Commercial banks increased their assets by more than one third, from less than $9 trillion to more than $12 trillion, and almost all the assets that would prove toxic in 2008 were among the additions

• Loan loss reserves were cut by 8 percent

• Financial institutions raised dividends 70 percent and engaged in aggressive stock buybacks — consuming equity capital that would be desperately needed after September 2008

• In the seven years from 1999 through 2005, $233 billion of asset-backed collateralized debt obligations were issued that ultimately resulted in $103 billion of losses. In just two years, 2006 and 2007, another $408 billion were added, resulting in $316 billion of losses

• The Federal Reserve raised interest rates four times between January and June 2006, from 4.25 percent to 5.25 percent

• At the start of 2006, Lehman’s balance sheet was composed of liquid assets in the process of being resold to clients. The firm then switched its strategy to holding large sums of illiquid assets, particularly leveraged loans, commercial real estate, private equity investments and riskier pieces of CDOs it could not sell. Everything that killed Lehman was bought in 2006 and 2007. Although the new businesses accounted for 90 percent of the risk, they were excluded from the stress tests and position limits the firm used to manage and report risk.

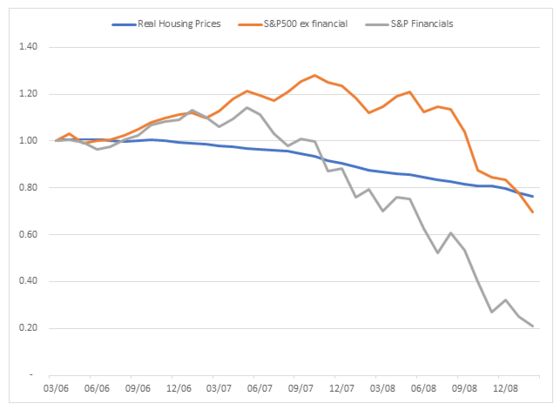

I could go on, but it should be evident that whatever the ultimate cause of the financial crisis, its size was determined by decisions made after the problems had become clear in early 2006. The chart below is another way to see this. It shows real housing prices steadily declining while financial stocks continued to rally for more than a year, rising as much as 14 percent by May 2007, before equity investors figured out that the housing crash might be bad for banks. It took another five months before non-financial stocks peaked, gaining 28 percent by October 2007, before investors began to suspect a financial collapse might cause problems for everyone.

Preventing bubbles is hard, especially without stifling innovation. It’s particularly hard for governments, who don’t see much to be gained politically by tempering the boom times and embarking on prudence. Once a crisis gets out of hand, all options are bad. What should be relatively easy is once things start going wrong to hold off on massive risk increases in the problem areas. If you don’t want to experience another 2008, figure out how to change 2006 – 2007 behavior.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Aaron Brown is a former Managing Director and Head of Financial Market Research at AQR Capital Management. He is the author of "The Poker Face of Wall Street." He may have a stake in the areas he writes about.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.