Greek Bad Loans Are a Drag Even After Crisis Shrank Bank Sector

Greek Bad Loans Are a Drag Even After Crisis Shrank Bank Sector

(Bloomberg) -- Ιra Tsinara had a front-row seat in Greece’s bad-loans drama.

The 44-year-old spent half of her 20-year banking career handling non-performing loans at one of the country’s biggest lenders. When she first saw the extent of such exposure at the bank in 2006 -- just two years before Greece became the epicenter of Europe’s financial crisis -- she was shocked.

“I was surprised to find that there were loans that hadn’t been paid back for almost 20 years; they had not been written off either,” she said. “This situation was clearly not sustainable, but we didn’t have the appropriate tools, updated computer programs or the legal framework, to deal with it.”

Ira is now a housewife, having accepted a buyout package from the bank in 2016, but the problem she saw 12 years ago lingers on -- Greece’s banks are still weighed down by bad loans. That’s making them cautious about new lending, which the country’s cratered economy needs to grow again after its European bailout ended on Aug. 20.

Greece’s banking sector has shrunk, with nine banks now from 40 before the crisis. Four of these are considered systemic and have been recapitalized three times during the crisis. Still, the biggest drag on the financial sector remains its bad loans. At the end of March, the non-performing exposure of the banking system stood at 92.4 billion euros ($107 billion), or equivalent to half the country’s gross domestic product. The European Central Bank’s supervisory arm is pushing banks to slash it by 30 billion euros by the end of 2019.

Steps Taken

Granted, banks have taken steps to streamline operations and cut costs. Greek banks have cut their staff to 40,000 at the end of 2017, from 66,165 in 2008, according data compiled by Hellenic Bank Association. They closed half of their branches to 2,000 in 2017 from 4,087 at the end of 2008.

After the country’s three bailout programs over the past eight years, the banking situation has improved. Recent stress tests by the ECB showed all four systemic lenders had common equity Tier 1 capital ratios above the legal minimum of 4.5 percent for an adverse scenario.

During the crisis, the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund injected 31.9 billion euros in the four systemic lenders. The current value of the bank shares the fund holds is about 6.5 billion euros, and a report by the European Court of Auditors last year estimated that only a small part of the 25.4 billion euros in expected losses is likely to be recovered over time.

That burden the banks put on the public coffers behooves them to do more for the real economy, says Emilios Avgouleas, a professor of International Banking Law and Finance at the University of Edinburgh.

Still Constrained

“It is essential for Greek banks to adopt a new business model, demonstrating they can generate revenue and become more bold in lending to enterprises,” he said. “Lenders must contribute to the recovery of the economy, and this is the only way to justify sacrifices made by Greek people to keep them alive.”

Greece’s economy is expected to expand 2 percent this year, although that growth is coming after GDP shrank by more than a quarter during the decade-long crisis. “Reviving bank’s lending capacity is critical for supporting the economy,” the IMF said in its concluding statement of the 2018 report.

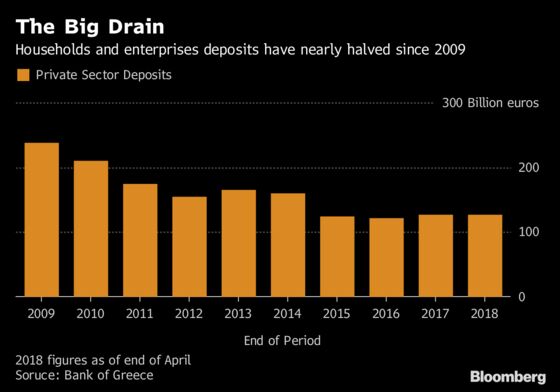

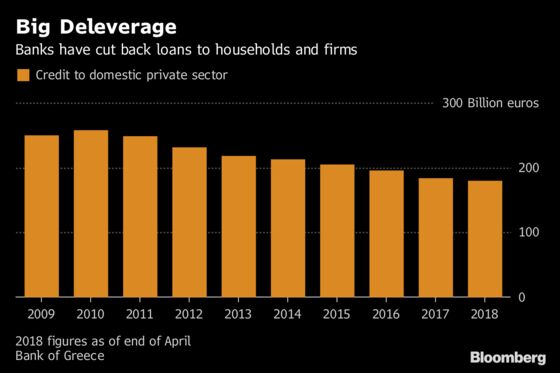

High non-performing exposures, which are still at more than 46 percent of the total loans, reduced deposits and squeezed liquidity continue to undermine the capacity of banks to lend to companies and households.

During the crisis, deposits at Greek banks fell by more than 110 billion euros. Lenders were forced to deleverage, shrinking assets to 259.7 billion euros by the end of 2017, from 418.6 billion euros in 2008, according data compiled by Hellenic Bank Association. Also, stuck with a junk rating since 2011, tapping markets was costly for banks.

In recent months, there have been signs of the environment improving. In July, Standard & Poor’s upgraded National Bank of Greece’s three-year covered bonds to the BBB- credit rating, four notches above the country’s credit rating. Deposits are beginning to rise, albeit at a very slow pace.

On the other hand, after the end of the bailout, the ECB ended a waiver that makes Greek bonds eligible for the central bank’s bond-buying program, depriving lenders of a cheap financing source. Greek banks reliance on ECB funding at the end of May stood at 11.3 billion euros.

Selling NPLs

To get bad loans off their books, Greek banks are selling them to funds. According to latest data published by Bank of Greece, the country’s banks have sold 6.9 billion euros of bad loans. They plan to sell an additional 4.7 billion euros by the end of 2019.

While this may be a quick solution, a more broad-based system is needed to help indebted companies and the economy to recover, said the University of Edinburgh’s Avgouleas.

“Selling NPLs at a very low price might help banks to meet targets but this isn’t the solution," he said. “Banks must cooperate with companies to work things out. They have to implement smart and flexible strategies to revive companies.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Christos Ziotis in Athens at cziotis@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sotiris Nikas at snikas@bloomberg.net, Vidya Root, Elisa Martinuzzi

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.