Argentina Is Playing a Risky Game in the Bond Market

Argentina Is Playing a Risky Game in the Bond Market

(Bloomberg) -- Struggling to staunch a run on the peso that has helped drive the economy to the brink of recession, Argentina is aggressively pushing investors out of some of the local debt notes they hold.

It is a risky gambit -- the opposite of the kind of measure a country would typically take at a moment of great financial duress. And yet Argentina finds itself pursuing the tack as part of a complex scheme aimed at shoring up investor confidence in its beleaguered central bank -- a step that policy makers believe is crucial to ushering in economic stability in a place long associated with default and runaway inflation.

If the gamble is to work, many of the investors who are being driven out of the notes they now hold -- popular short-term securities that were issued by the central bank at interest rates that reached 47 percent -- will have to be persuaded to plow their money into newer debt instruments being dangled by the government.

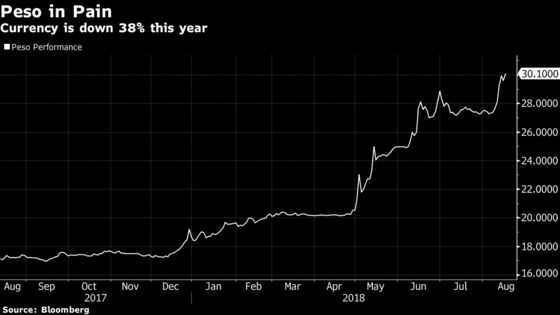

The catch: the new securities have maturities of as long as a year, more than 10 times longer than those on most of the old notes. And it isn’t clear who would want to tie their money up in the peso for longer periods of time in the middle of a full-blown crisis. The concern is that investors will opt to buy dollars with the cash instead, which would only add to the peso’s 38 percent plunge this year.

“It is highly risky,” says Walter Stoeppelwerth, the chief investment officer at Buenos Aires-based Balanz Capital. While the push to strengthen the central bank’s balance sheet makes sense, “they waited too long to undertake the process.”

The first major indication of whether this strategy will work out will be revealed later today when the government announces results of an auction of peso-denominated notes known as Letes that mature in 105 or 224 days. (One initial troubling sign came in last night when the central bank failed to sell another longer-term security, with investors opting for short-term notes.)

The peso weakened 1.3 percent Wednesday, closing at 30 pesos per dollar, even after the central bank sold $781 million through three foreign exchange auctions during the day.

Macri’s Arrival

At the core of the problem are short-term central bank notes known as Lebacs, which became popular investment instruments when the central bank jacked up rates in December 2015 just as President Mauricio Macri lifted currency controls imposed by his predecessors.

The notes mopped up excess cash in the economy and helped dampen inflation but became a growing concern for investors as the amount in circulation swelled to 976 billion pesos ($32.5 billion). They were structured in such a way that more than 500 billion pesos of the securities would come due in some months, creating market volatility as investors nervously eyed the rollover risk.

The situation was worrying enough that the International Monetary Fund demanded Argentina address it as part of a $50 billion credit line that largely had managed to calm local markets until the crisis in Turkey sparked a new wave of selling across the developing world.

So the central bank, led since June by former Finance Minister Luis Caputo, unveiled a plan Monday to phase out all of its remaining Lebacs by the end of the year and largely replace them with debt issued by the Treasury. The central bank will offer fewer of the Lebac notes for rollover in each sale until December, when the aim is to have eliminated them entirely.

Concern about runaway consumer prices and a rapidly depreciating currency has already prompted the central bank to jack up interest rates. Policy makers set the benchmark rate at a record 45 percent on Monday -- the fourth surprise increase this year -- and pledged to keep it at that level at least until October.

While a surge in dollar demand poses a risk of undermining the peso, the IMF credit line gives policy makers a big chunk of dollars they could use to meet demand and limit volatility. Argentina has $56 billion in reserves, more than double the level when Macri came into office. The speculation among investors is that authorities won’t mind some percentage of the proceeds from expiring Lebacs going into the foreign-exchange market, but the key is getting the right balance.

In its first auction since the announcement, the central bank rolled over 201 billion pesos in Lebacs on Tuesday, less than the 330 billion pesos worth of maturing securities eligible to rollover.

“It’s not a bad plan if they coordinate well between the central bank and Treasury, but it’s not risk-free,” said Carlos de Sousa, a senior economist at Oxford Economics in London.

For policy makers to claim success, they’ll need to sell the equivalent of $11 billion of securities to absorb liquidity over the next few weeks -- or about two-thirds of the amount of Lebacs maturing -- De Sousa said.

“If it’s less, it would be worrisome because there would be substantial excess liquidity,” De Sousa said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Carolina Millan in Buenos Aires at cmillanronch@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Courtney Dentch at cdentch1@bloomberg.net, David Papadopoulos, Brendan Walsh

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.