Tesla Does Some Going-Private Stuff

Tesla Does Some Going-Private Stuff

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Programming note: Money Stuff will be off for the next three weeks while I take a break and work on some other things. There may be a newsletter here and there, but regular service will resume after Labor Day.

Tesla Funding Watch 2018.

Well there’s no news. I mean, there’s news; there are tons of articles about Elon Musk’s vague proposed buyout of Tesla Inc., and many of them contain new and interesting information. But none of that information is along the lines of “when Musk said ‘funding secured’ for his deal, he meant that he had sufficient committed financing from _____.” So, three days after Musk tweeted that he was considering taking Tesla private at $420 a share and had secured funding for the buyout, we still don’t know if he was … kidding? And this is not a great sign!

Tesla Inc’s board has not yet received a detailed financing plan from CEO Elon Musk, and is seeking more information about how he will take the U.S. electric car maker private in a proposed deal worth $72 billion, people familiar with the matter said on Thursday.

While Tesla’s board has held multiple discussions about Musk’s proposal, which first became public on Tuesday, it has not yet received specific information on who will provide the funding, one of the sources said.

Ahhhhhhhhhh what. What were the “multiple discussions” about? I feel like if someone comes to you and offers to buy something for $80 billion, one of your very first questions should be “wait do you have $80 billion?” There are lots of other interesting questions that are worth discussing in this weird quasi-buyout quasi-proposal, but that really is critical. Don’t get me wrong, lovingly crafting the governance and securities-law details of a hypothetical buyout that allows public shareholders to continue to participate is, in certain circles, considered a good time, but I am not sure it is the best use of the board’s time, unless they think it is more than hypothetical. “The sequence of events suggests that ‘the board review has been very, very informal.’”

In any case the board is definitely doing some things:

The Tesla board of directors plans to meet with financial advisors next week to formalize a process to explore Elon Musk's take-private proposal, according to people familiar with the matter. ...

The board is likely to tell Musk, the Tesla chairman and CEO, to recuse himself as the company prepares to review his take-private proposal, according to these people, who asked not to be named because the conversations are private. The board has told Musk that he needs his own separate set of advisors, one of the people said.

Tesla's board will likely develop a special committee of a smaller number of independent directors to review the buyout details, the people added.

I mean, of course. When the chief executive officer and chairman of the board of a public company approaches the rest of the board with a proposal to take the company private, his position with respect to the company immediately changes. He is no longer working on behalf of the public shareholders. He has his own plan, one that creates a fundamental conflict of interest between him and the shareholders, and it is the job of the rest of the board to make sure that those shareholders get a fair deal. Of course the board will hire advisers to consider his proposal, and tell him to hire his own advisers, and demand that he recuse himself from the board’s deliberations, and form a special committee of disinterested directors to consider his proposal and negotiate on behalf of shareholders. Those are basic demands of decent corporate governance; that’s how every management buyout goes; that’s the bare minimum.

That is just what you do—if the CEO has come to you with a real going-private proposal. But if he comes to you and says “I would like to take the company private for $80 billion” and you say “where are you getting the $80 billion” and he holds out a handful of beans and says “THESE ARE ENCHANTED” and starts to dance a jig, forming a special committee seems premature. If that’s what’s going on—if this fully funded going-private transaction is in fact an elaborate Twitter trolling operation—then you don’t need to form a special committee to negotiate the terms. You do need to hold a board meeting without the CEO present. But the topic of the meeting will not be what to do about the buyout proposal. It will be what to do about the CEO.

Of course if this fully funded going-private transaction is in fact a Twitter trolling operation—if Musk announced a buyout proposal, and caused the stock price to shoot up on huge volume, but never had a real funded plan in place to take Tesla private—then the Securities and Exchange Commission will also be very interested, and will have its own meetings to consider what to do with Musk, and the tone of those meetings will be a lot less friendly than the tone of a Tesla board meeting. Here is a funny article about how “The SEC Is Intensifying Its Probe of Tesla,” funny in the sense of, like, the inquiry here is doubtless intense, but it is not complicated. (Also in the sense that the SEC is “examining whether Musk’s tweet about having funding secured to buy out the company was meant to be factual,” which, I didn’t realize that it was optional for a CEO’s public statements about fundamental change-of-control transactions to be factual.) Here’s how I’d do it:

SEC (calls Tesla): So where is the financing coming from for this going-private transaction?

Tesla: Funny story actually, we don’t know. But you could call Elon?

SEC (calls Musk): So where is the financing coming from for this going-private transaction?

Musk: It is coming from my good friend Gandalf the Grey! Would you like a bean?

SEC: Ah. Do you have a phone number for Mr. the Grey?

Musk: He lives in the moon!

Like, I don’t know, in 24 hours of regulatory inquiry, you either see a financing termsheet or you don’t. If you do, then there’s no need to intensify anything. (As Dan Primack tweeted: “These growing leaks about SEC investigations into Tesla suggest that the company didn’t just say: ‘Sure. firm X and firm Y agreed to fund elon's bid.’”) If you don’t, then you start using words like “securities fraud” and “market manipulation.”

Of course securities plaintiffs’ firms are already looking for clients to sue Tesla.

What will happen here? One possibility is that Musk has $80 billion in committed financing that he has kept secret for Reasons, and he will eventually reveal who is providing it, and everyone will be like “oh right that guy, of course,” and then this will proceed to be just a very weird and interesting management buyout negotiation. Another possibility is that he was just kidding, just trying to troll short sellers on Twitter, and then this will proceed to be just a very weird and interesting securities-fraud investigation.

The intermediate possibility is that there is some sort of deep misunderstanding, that when Musk tweeted about “taking Tesla private at $420” and having “funding secured,” he didn’t mean what you and I and the SEC normally interpret those words to mean, which is that he would make a binding offer to buy any Tesla shares not owned by Musk and his financing partners for $420 a share in cash.He meant something more like: He would like to not be subject to the obligations of being a public company anymore, and it would be nice if there was a way to do that. After all Musk immediately followed up by tweeting about letting shareholders continue to own their shares in a “private” Tesla, which is not how going-private transactions normally work. There has been a lot of speculation about how that could be done, and I remain a bit skeptical, but the important point here is that if Musk believes that (1) there is actually a way to “go private” while keeping all of his existing shareholders and (2) most of his existing shareholders love him and would prefer to stay private with him, then he could rationally believe that he doesn’t need much financing. If no one will take the cash, then you don’t need any cash. Both of those things are kind of weird things to believe, but neither of them seems impossible for Musk to believe.

If I were Musk’s lawyer, and if he doesn’t actually have $80 billion of financing locked up, I’d be working on a termsheet for the board that (1) offers Tesla shareholders the choice between (A) $420 in cash or (B) shares in a new special-purpose-vehicle that will hold shares in a private Tesla (or whatever your plan is to let people hold on to their shares); (2) limits the cash consideration to, like, $5 billion, or whatever Musk can actually raise; and (3) has some sort of proration mechanism in case more people choose the cash than he can afford. Does this fit with the spirit of the going-private transaction that Musk tweeted about? No, absolutely not, not even a little bit. But it is … something. And then let the special committee reject it, and then quietly walk away and say “well no we were serious about the buyout proposal but it just didn’t work out.” Which is a much better position to be in than walking away saying “oh yeah sorry we were kidding about that.”

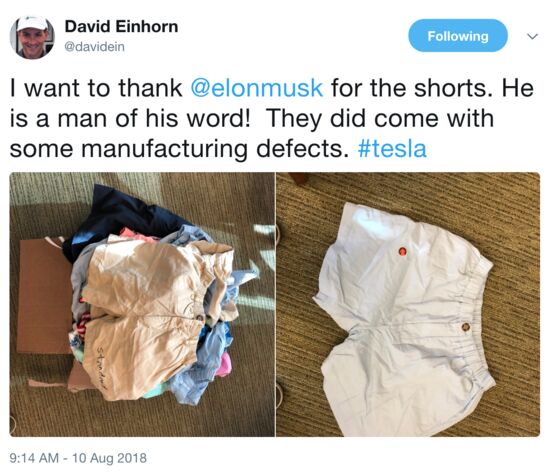

Elsewhere, hedge-fund manager David Einhorn is short Tesla, and Musk joked on Twitter last week that he would send him a box of shorts “to comfort him through this difficult time,” and today Einhorn tweeted:

So, first of all: Great tweet, just a tremendous burn. Second, though, one problem for Musk is that if he doesn’t go through with an actual deal, his much-publicized war on short sellers is going to be taken as evidence of an intent to manipulate the stock: You could easily believe that he wasn’t just randomly joking about going private, but that he was doing it in order to squeeze short sellers. This is not a great time for him to be pulling pranks on short sellers! I am looking forward to these shorts being entered into evidence at a trial. Unless Einhorn is also just trolling.

Banking fees.

Sujeet Indap wrote about an early proposed business plan for Ducera Partners, the boutique investment bank formed by some bankers who left Perella Weinberg Partners in 2015. (Perella Weinberg and Ducera are suing each other over those departures, which is why this business plan is public; my advice to people in secretive areas of finance is: Sue each other more!) “The spoils of being a partner at an investment bank” is the headline of his post; the highest-paid hypothetical partner hypothetically takes home about $7 million of the firm’s $30 million of hypothetical revenue. The lowest-paid makes $832,000, barely more than the $750,000 paid to directors, the next-highest-ranking employees. (In real life, Ducera made a $45 million fee on one deal in 2016, so this probably understates things.) In any case, if you want to see a back-of-the-envelope (well, back-of-the-book2.xlsx-spreadsheet) business model for a boutique investment bank, there it is.

To me the interesting thing about the spreadsheet is its simplicity. There is hardly any math. There are nine partners in the pro forma firm, and they advise on some deals (six a year, total), and companies pay for their advice, and they use about a third of those payments to pay for rent and Bloomberg terminals and junior banker salaries, and they take home the rest. The business model is just, we give you advice, and we send you a bill, and you pay it, and we keep the money. You know how much you’re paying, because we send you a bill; you know what you’re paying for, because it’s advice that we’re giving to you directly; and you presumably think it’s worth it, because otherwise you wouldn’t pay. There is no mystery, no balance sheet, no cross-selling, no conflicts with other departments, no derivatives that could blow up in the client’s face. If you were a managing director at a big investment bank—not so much Perella Weinberg, which is also pretty boutique-y—and you saw this spreadsheet, it might tempt you to jump, not because the money is so good but because the model is so simple.

Elsewhere in the spoils of investment banking: “Deutsche Bank Cuts Again. Not Even Fruit Bowls Are Safe.”

Notorious.

Here is a story about Christopher Rollins, a former sales-trading managing director at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (disclosure: where I used to work), who did some trades that somehow involved a “notorious European businessman,” and then those trades ran into settlement and compliance problems, and Rollins got in trouble and was eventually fired. He is now suing, claiming that he was just a scapegoat, and that the notorious client was brought into the firm, and vetted (or not), by quite senior Goldman bankers. It is hard to assess the truth of these allegations, or really even to figure out exactly what they are, but anyway they involve a big yacht:

Rollins’s story begins in August 2015, when two Goldman Sachs senior bankers, Michael Daffey and John Storey, allegedly met with a financier on board his 200-foot superyacht in the Mediterranean Sea. The financier, who’s not identified by name in the complaint, also had a jet and said he had more than $1 billion to invest, according to Rollins.

Here is Rollins’s complaint. Again it is all a bit confusing and I am not sure what to believe, but on general principle I am sympathetic. Investment banks consist of lots of different businesses. If you are a mid-level person in charge of one business, and a very senior person in charge of another business comes to you and says “here’s my guy, hook him up,” it is hard for you to say “sure okay but first tell me: Is he a crook?” If your colleagues—particularly your more powerful colleagues—have vouched for a client, it looks a bit disrespectful for you to start vetting the client from scratch. But then if the trades you do for the client go south, you will have a tough time blaming the colleagues who foisted him off on you.

Oops!

Yesterday I formulated a Ninth Law of Insider Trading, which is “if you are already under a federal ethics investigation about your ownership or promotion of a stock, don’t insider trade that stock.” But I had forgotten, as I sometimes do, that I had already formulated a Ninth Law, back in October 2017. That one was “If you are going to insider trade, do it in a company that is far away from a Securities and Exchange Commission office. Like, physically.” So I guess the one about ethics is the Tenth Law. This was pointed out to me by reader Mike Peattie, who emailed:

In today's Money Stuff you document a new Ninth Insider Trading Law, but since I often forget them, I've documented past Laws in a Google Doc.

So, one, great idea, I hope all of my readers keep spreadsheets of the important Money Stuff highlights, even the ones that are not legal advice. (None of them are legal advice.) Two, obviously I should be doing this; it’s particularly embarrassing when I can’t keep track of these laws. They are my laws, after all. In any case, here are all the Laws in one place:

- Don’t do it.

- Don’t do it by buying short-dated out-of-the-money call options on merger targets.

- Don’t text or email about it.

- Don’t do it in your mother’s account.

- Don’t do it by planting bombs at a company and shorting its stock.

- Don’t do it while employed at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Don’t Google “how to insider trade without getting caught” before doing it.

- If you didn’t insider trade, don’t forget and accidentally confess to insider trading.

- If you are going to insider trade, do it in a company that is far away from a Securities and Exchange Commission office. Like, physically.

- If you are already under a federal ethics investigation about your ownership or promotion of a stock, don’t insider trade that stock.

Also though Mike Peattie’s email suggests one more Law:

The Eleventh Law of Insider Trading is that if you are planning to insider trade, probably don’t keep a Google Doc spreadsheet of the Money Stuff Laws of Insider Trading. That will definitely show up in the SEC’s complaint against you. If you’re gonna insider trade, you have to keep track of these rules in your head, even at the risk of forgetting a few now and then.

I said it above but it bears repeating: None of this is legal advice. Probably put that at the top of your spreadsheet.

Things happen.

U.S. Judge Authorizes Seizure of Venezuela’s Citgo. Dell Still Has Some Explaining to Do on Its Deal Math. WeWork Gets Another $1 Billion From SoftBank. Pershing Square is up 12.7 percent year-to-date. Credit Market’s ‘ Eyeball Valuations’ Raise Investors’ Eyebrows. Viacom’s Redstone Jumps Through Big Disclosure Loophole. Cryptokidnapping, or How to Lose $3 Billion of Bitcoin in India. The OG Yield Curve Whisperer. “I’d check into a movie I had no intention of seeing just so I could use the bathroom,” says heavy MoviePass user. “I wanted something unique and different and for customers that love taking pictures,” says food-truck owner who is selling Spam wrapped in gold for $100.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matt Levine is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering finance. He was an editor of Dealbreaker, an investment banker at Goldman Sachs, a mergers and acquisitions lawyer at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, and a clerk for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.