Juul Knows It Has a Popularity Problem

Juul Knows It Has a Popularity Problem

As the electronic cigarette brand has exploded in popularity over the past year — its sales now amounting to more than half of all e-cigarette sales — it has developed a terrible reputation in the public health community.

“This could be a highly addictive product for youth,” warned Adam Leventhal, an addiction scientist at the University of Southern California, in the Wall Street Journal a few months ago. The Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, as well as the Bloomberg Opinion editorial board, has called on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to regulate e-cigarettes in the wake of Juul’s popularity. “Juul swept through high schools across America without most parents even knowing it existed,” Matt Myers, the head of Tobacco-Free Kids, told the Journal.

Jonathan Winickoff, a professor at Harvard Medical School told the New Yorker that “if you were to design your ideal nicotine-delivery device to addict large numbers of United States kids, you'd invent Juul.”

The brief against Juul, then, is simple: whatever good it might do in weaning adult smokers off cigarettes is overridden by the grim possibility that its popularity — and its nicotine content — could result in young vapers becoming lifelong addicts.

Yet here was Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller, talking to me the other day, and making the case that teenage e-cigarette use was much ado about not a whole lot:

About 80 percent of e-cigarette use by teenagers is experimental, much more so than with combustible cigarettes. Second, the great fear of e-cigarette use by youths is that it will serve as a gateway to a cigarette addiction. But there is no evidence of that. Third, the science claiming that nicotine harms young brains is exceptionally weak — heck, Einstein was a kid smoker.

Finally, Miller noted, the statistics on youth smoking in recent years — years during which Juul became a “thing” in upscale high schools — were so good that tobacco-control officials should be throwing a parade. “I find it pretty reassuring,” he told me.

If you think this sounds like some kind libertarian crank, think again. Miller, a Democrat who at 73 is the longest-serving attorney general in the country, has serious anti-tobacco credentials. In the 1990s, he was one of the first to sue Big Tobacco, and then helped negotiate the $200 billion-plus settlement between 46 states and the five largest tobacco companies. He sat for years on the board of the Truth Initiative, a group dedicated to reducing smoking that was born out of the settlement. He is the rare official who talks to the principals on both sides of the highly contentious cigarette versus e-cigarette divide.

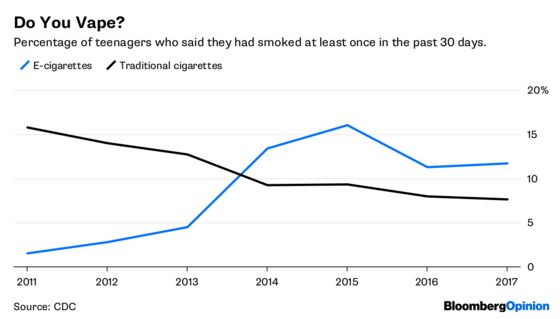

And if you look at the statistics, you’ll see that he’s completely right about what’s been happening to youth smoking. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2011, 15.8 percent of high school students smoked at least one cigarette in the 30 days prior to the survey — while only 1.5 percent tried an e-cigarette. Six years later, in 2017, 11.7 percent of high schoolers had tried an e-cigarette, but the number of cigarette users had fallen in half, to 7.6 percent. That last number is astonishing: It means we are closing in on the elimination of youth smoking. What an accomplishment that would be!

The drop in adult smoking is also encouraging. Between 1965 and 2006, adult cigarette use dropped from 45 percent to 20 percent. But then it seemed to stall, fluctuating between the low 20s and high teens — until it began dropping again in 2012. Last year, adult smoking dropped to 13.9 percent of the U.S. population. That, too, is an all-time low.

Although the public health community is loath to acknowledge it, the decrease in smoking correlates pretty straightforwardly with the increase in vaping. Which, as Miller sees it, is something worth rejoicing rather than bemoaning. Although he does not deny nicotine’s addictive power, he likes to point out that it is the lit tobacco in a cigarette that kills smokers — not the nicotine. If you can supply nicotine without tobacco, as Juul is doing, your product may still be addictive but it won’t be deadly.

The reason I had called Miller was that he and Juul had issued a news release this week announcing an alliance of sorts. It said that Miller had formed a committee that would advise Juul on ways “to keep its e-cigarette products out of the hands of young people” — precisely what public health officials have been demanding. Miller’s group included several well-known e-cigarette advocates. But it was dominated by former attorneys general, men and women who, like Miller, had fought Big Tobacco, but who had come to believe that a different approach was now needed to end the scourge of smoking in the U.S.

That approach is called harm reduction: replacing something that causes significant harm with something that causes less harm. This is not an uncommon strategy in public health. Heroin addicts, for instance, are often given methadone as a substitute. With smoking, the idea is that while e-cigarettes may not be completely harmless — the jury’s still out on that — they are certainly safer than a lit cigarette. Many of the e-cigarette companies that have cropped up claim to be specifically targeting adult smokers.

This is especially true of Juul, which was invented by two product design guys, James Monsees and Adam Bowen, who began working on an e-cigarette because, as smokers themselves, they were dissatisfied with the cessation devices on the market. They came up with a product that more closely replicated the nicotine hit of a cigarette than competing devices. But they also wanted a device that didn’t tempt users to return to smoking. Thus, the shape of a Juul is rectangular — not cylindrical like a cigarette. Sleek and digitally rechargeable, it feels more like something Apple would make than Philip Morris. Its “pods” come in a variety of flavors — something all e-cigarette companies do — because that too creates a difference experience than smoking a cigarette. And so on.

The company, Juul Labs Inc., is also conducting a series of clinical studies aimed at nailing down exactly how effective Juul is at getting adult smokers to quit for good, and how much safer it is than smoking a cigarette. But all of these good intentions are overshadowed, in the collective mind of the public health community, by the way high school kids have embraced Juul.

Although you wouldn’t know from listening to the public health rhetoric, the company has actually gone to considerable lengths to keep kids from getting their hands on a Juul device. For starters, it has done very little marketing — and none aimed at youths. It insists that buyers of its product be 21, and has a sophisticated program to prevent underage sales online. It has a “secret shopper” program to make sure retailers are abiding by the age stricture. It has worked with the big Internet platforms like Facebook to reduce posts and photographs that might entice kids to use Juul. And yes, it has flavors, which many adult vapers like, but it does not make “cotton candy” or “bubble gum” or the like that are clearly aimed at younger tastes.

Although it’s hard to think of what else the company could do, it’s obviously not enough. Which is why Juul has turned to Miller and his group, in the hope that they might have fresh notions to help make Juul “uncool” among high school kids. If they could succeed at that, then maybe — just maybe — the public health community might finally be willing to accept the idea that e-cigarettes offer our best chance to eliminate smoking in the U.S. and save millions of lives.

My own view is that the simplest way to reduce the use of Juul in high schools is for the adults to follow Miller’s example and stop obsessing about it. Kids have always been drawn to the forbidden — and the more public health officials denounce Juul, the more they will want to sneak in a few vapes between classes. Besides, no matter what Juul — or the public health community — does, the company will never be able to eliminate high school vapers. Underage kids have no problem obtaining alcohol. They smoke pot and take other drugs. They can access cigarettes. Adult messages have reduced such risky behavior, but they haven’t eliminated it. The same is now true of vaping.

To Miller — and to me — replacing smoking with vaping is well worth the trade-off. That is obvious in the case of adult smokers. But I think it is also true of youths. Thanks to Juul and other e-cigarettes, the incidence of youth smoking has been cut in half. That means millions of young men and woman will avoid growing up with a cigarette addiction that they will struggle (and in many cases fail) to abandon later in life.

Will some of them become addicted to less harmful e-cigarettes? No doubt. But most of them won’t, and even those who do are not risking death the way a cigarette addict is. In any case, the most sensible policy would be one that discourages youth vaping while actively encouraging adult smokers to switch.

On its website, Juul says, “We envision a world where fewer people use cigarettes, and where people who use cigarettes have the tools to reduce or eliminate their consumption entirely.”

Should we really be denouncing a company with that goal? Or should we be encouraging it?

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.