The $3 Trillion Thumb on the Bond-Market Scale

Managers of huge retirement funds, by most accounts, are in the midst of a big shift into bonds.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The $3.2 trillion corporate pension industry has quietly been throwing its weight around the bond market.

Managers of the huge retirement funds, by most accounts, are in the midst of a big shift into bonds. The move makes perfect sense, given that the plans are as well-funded as they’ve been in years. After all, equities remain close to record highs, so defined-benefit systems should naturally cash in and buy fixed-income assets, which more closely resemble their liabilities.

Plus, new tax legislation gives companies a further push to fund their pensions — they can lock in a higher deduction for those contributions through September. All the while, fees from the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. are making it expensive for corporate America to shortchange retirement plans. These are all positive developments for the health of these systems and for the retirees who may depend on the promised income.

What’s less clear, however, is whether this trend is healthy for bond markets.

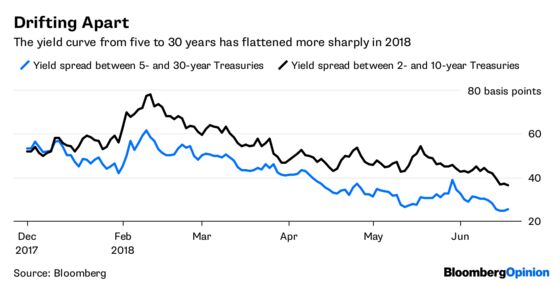

There’s good reason to believe that pension demand for long bonds is an unseen driving force behind the flattest U.S. yield curve since 2007. And if that’s the case, investors and Federal Reserve officials may be getting needlessly worked up about an impending recession.

Defined-benefit pensions, as the name implies, promise to pay retirees a set amount, usually based on a formula that takes into account age, salary and length of employment. To offset these long-term liabilities, the plans would ideally buy enough bonds with long maturities to match up principal and interest payments with payouts. The process, known as immunization, is far safer than counting on outsized stock-market profits or the performance of hedge fund managers. But it also demands a higher upfront cost and has less upside. Until now, pensions have had little incentive to reduce risk.

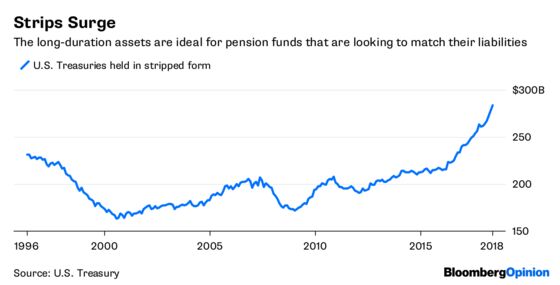

That’s changing, and it’s showing up in the market for Treasury Strips, a favorite of pension funds looking to match cash flows. Strips — an acronym for Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities — climbed almost $6 billion in May to a record $284 billion. They now command the largest share of the U.S. government bond market since 2014.

The longest bonds are the most likely to be broken into their component cash flows. The demand is keeping 30-year yields relatively contained around the highs of the past few years even as shorter-term notes reach the loftiest levels in nearly a decade.

Naturally, that difference is showing up in the U.S. yield curve. Heading into 2018, the gap between two- and 10-year notes was nearly identical to the difference between five- and 30-year Treasuries. But that hasn’t been the case for months. In fact, at one point a few weeks ago, the spread from two to 10 years was almost twice that of the five- to 30-year segment.

Simply put, the vast amount of money that pensions can pour into long bonds, and the limited time frame they have to seize on the tax policy, mean the yield curve might not be the existential threat to the U.S. economic expansion that some fear.

The question, then, is how markets will react in the coming months when the yield curve most likely gets even closer to inverting. Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic warned Monday that the flattening “is not something we can afford to be too cavalier with and think this time is different.” He added that the curve “could trigger its own response that would increase volatility in the marketplace.”

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell seemed less concerned last week after the Fed raised interest rates for the second time this year. “It makes all the sense in the world that the short end would come up. The harder question is what’s happening with long rates?” he said. “There may be a signal in that long-term rate about what is the neutral rate.”

But if you believe pensions are bringing forward much of their demand for fixed-income assets, that long-term rate may be artificially low. While buyers of shorter-dated Treasuries may demand a premium to clear the market, the process of matching assets and liabilities is largely price insensitive. The difference between 3 percent and 3.25 percent, when thinking in terms of three decades, seems inconsequential.

Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank, said that one reason to be worried about long-term yields increasing toward the end of 2018 is that pensions could pull back from the bond market. Others include concerns about the economy overheating and increased Treasury issuance to cover budget deficits.

Any sustained increase in long-term yields would have lasting implications. For one, it would make the Fed’s median 2019 and 2020 dots, at 3.125 percent and 3.375 percent, look more realistic. It would keep margins healthier at banks, which prefer a steeper curve because they generate income from the spread between long-dated loans and deposits based on shorter-term rates. It could finally bring “term premium” up from below zero.

That’s a lot riding on the actions of a few big pension funds. According to a report from Priya Misra at TD Securities, seven of the 100 largest defined-benefit pensions contributed more than $1 billion to their plans in the first quarter of 2018, the same as during all of 2016. So called risk transfers are likely to climb as well, she said. Earlier this year, FedEx Corp. transferred about $6 billion of its U.S. pension obligations to MetLife Inc., the largest transaction since Verizon Communications Inc. shifted $7.5 billion in 2012.

Throwing around billions of dollars can keep the bond market gliding in one direction and telling one story. But the pension frenzy doesn’t seem sustainable forever. And should the money slow down, traders may get a clearer signal from the yield curve about the economic outlook.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.