Tax Hikes, Not `Brexit Dividend,' Will Pay for May's NHS Boost

Tax Hikes, Not `Brexit Dividend,' Will Pay for May's NHS Boost

(Bloomberg) -- Follow @Brexit on Twitter, join our Facebook group and sign up to our daily Brexit Bulletin.

U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May’s big announcement of more money for the cash-strapped National Health Service should have been an easy political win. Instead she’s dug herself in a hole over how to pay for it.

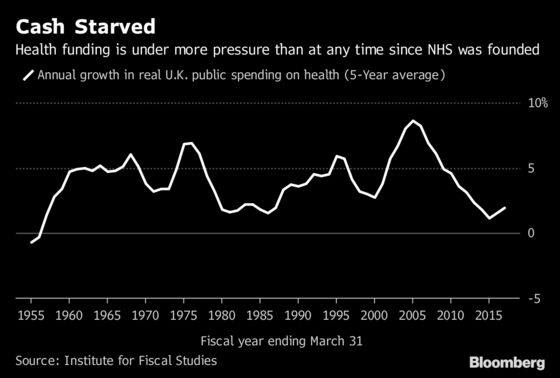

After the worst winter on record for the NHS, the much-loved institution is in dire need of fresh funds but a decade of severe spending restraint means the extra cash will almost certainly have to be generated by increasing taxes, something the Conservatives have traditionally been reluctant to do, though opposition to the idea appears to be softening.

Dodging the awkward question of who will pay, May promised an annual 20 billion pounds ($26.5 billion) for the NHS by 2023, funded by a Brexit dividend -- the 350 million pounds a week that Britain will no longer have to pay into the EU budget as a result of leaving the European Union.

“Some of the extra funding I am promising today will come from using the money we will no longer spend on our annual membership subscription to the European Union after we have left,” May insisted during her speech on Monday.

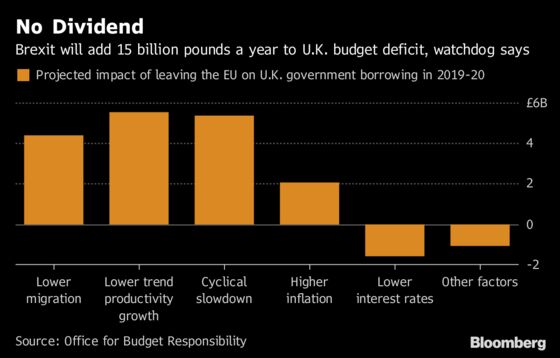

But that figure, famously advertised on the side of the pro-Brexit campaign bus back in 2016, ignored the money that Britain gets back from the EU. Britain will also still be paying billions of pounds to the EU well into the next decade under its divorce settlement. And according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, Brexit will cost Britain 15 billion pounds in lost tax revenue, more than wiping out the benefits of reducing payments to the EU.

“There is literally arithmetically no money,” Institute for Fiscal Studies Director Paul Johnson told the BBC.

Even the self-declared Socialist Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell accused Theresa May of shaking a "magic money tree" to find the extra cash, saying the announcement was just a publicity stunt.

May quietly added the country would be “contributing a bit more.” meaning taxes would have to rise. That bit would need to reach an additional 1,200 to 2,000 pounds per household a year by 2033 to 2034, according to the IFS.

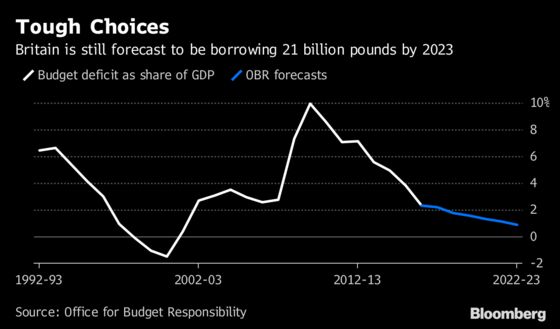

May’s announcement may be more about saving the Conservative party, but Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond will still have to come up with the cash. Without tax increases, Hammond would almost certainly be forced to abandon his plans to erase the budget deficit by the middle of the next decade. Even on current plans, Britain is still on course to be borrowing 21 billion pounds in the 2022-23 fiscal year, according to official forecasts.

Short of looking under the sofa cushions, these are the places he may find it.

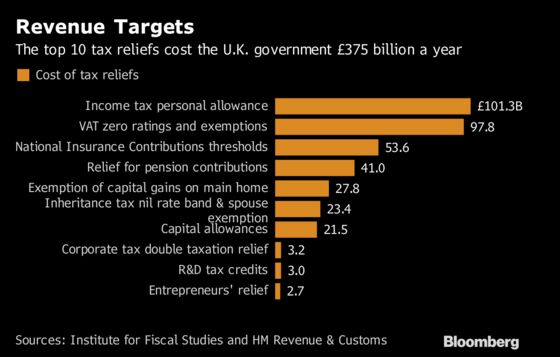

1. Income tax

Income tax accounts for more than a quarter of total revenue, and raising the levy might not be as unpopular as Hammond may think. Two thirds of voters said they would be willing to pay one penny more in the pound in income tax to help the NHS, according to a YouGov survey. That extra penny would raise about 5 billion pounds, according to the IFS. Though on the flip side, taxes on earnings can discourage people from getting jobs, it says.

2. National Insurance

In 2002, then Chancellor Gordon Brown announced a 1 percent hike in national insurance contributions, a payroll levy, to help finance a 6.1 billion-pound increase in health spending and it was a popular policy. If Hammond raised the main rates of employee and self-employed NICs now, along with the employer rate, by 1 percent, he could raise about 9.9 billion pounds, the IFS says.

3. Corporation Tax

Since 2010 the government has slashed corporation tax in an effort to boost investment. The opposition Labour Party has promised to reverse these cuts -- a move that could raise about 18.6 billion pounds if it doesn’t discourage investment, the IFS says.

4 Personal Allowance

Hammond could reverse some of the recent increases to the personal tax-free allowance, which is the threshold at which people start having to pay tax on their earnings. Lowering the allowance by 1,000 pounds could raise about 5.8 billion, while reducing the basic-rate limit, at which people start paying a higher amount of tax by the same amount could raise 400 million pounds.

5. Rich People

Wealth taxation could be another option for Hammond, according to David Willetts, the Conservative peer who was a universities minister and now chairs the Resolution Foundation think tank. It wants to see a change to inheritance tax to even out the country’s widening gap between rich and poor and the inter-generational divide. The Foundation has called for inheritance tax to be replaced with a new system that can more fairly distribute wealth throughout the country.

6. Borrowing

Finally, Hammond also has the option of leaving taxes as they are and increasing borrowing instead. The chancellor has already promised a spending review in 2019 that is expected to look at loosening the public purse strings to fund the NHS. Though on Monday, bonds had barely moved, suggesting traders don’t see this as a realistic option and may be awaiting more detail from May.

Drop in the Ocean

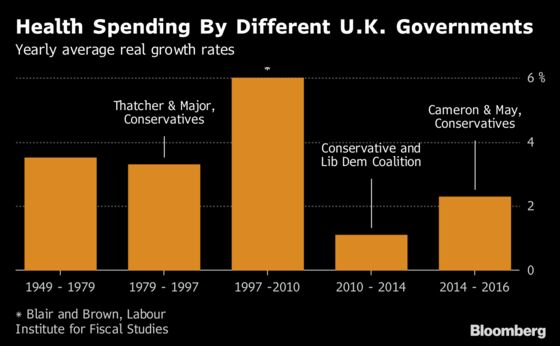

Whichever way Hammond manages to come up with the cash by the autumn Budget announcement, most experts think the pledge simply isn’t enough to pull the NHS out of its black hole. The boost is the equivalent growth of about 3.4 percent a year, which is about the same amount that the Margaret Thatcher and John Major governments gave. Neither of those Tory prime ministers were known for being big financiers of the NHS.

“An average 3.4 per cent increase in NHS funding would be welcome but historically unremarkable, a little less than the long-run trend of 3.7 per cent,” said Tom Kibasi, director of the IPPR think tank.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jessica Shankleman in London at jshankleman@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Flavia Krause-Jackson at fjackson@bloomberg.net, Andrew Atkinson

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.