Bill Gross's ‘Trade of the Year’ Misses a Key Fact

Bill Gross's ‘Trade of the Year’ Misses a Key Fact

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Less than 24 hours after Bill Gross confidently declared that his “trade of the year” was going to work out, European Central Bank President Mario Draghi dealt his wager a body blow.

The ECB surprised traders on Thursday by pledging to keep interest rates unchanged at least through next summer, sending the euro into a tailspin and spurring a rally in bunds. The 10-year German yield fell about 6 basis points to 0.43 percent, the lowest in more than a week. Treasuries rallied too, but to a lesser extent.

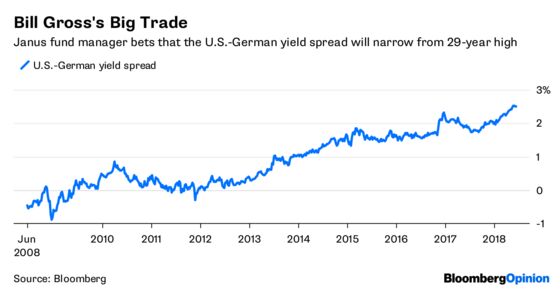

What that means, of course, is that the spread widened between 10-year U.S. and German yields — the opposite of what Gross is betting on in his $1.7 billion Janus Henderson Global Unconstrained Bond Fund. The gap reached 2.59 percentage points in late May, the largest since 1989. So even a hint of mean reversion would make that wager wildly profitable. But the fact that the ECB is holding its benchmark at zero for a long while, just as the Federal Reserve is planning to step up the pace of near-term rate hikes, suggests the divergence is likely to remain intact.

Reading the minds of ECB and Fed officials is a tough task, for sure. Yet even before the central bank announcements this week, a yearlong trend in global bond and currency markets should have made Gross wary of betting on the Treasury-bund yield spread.

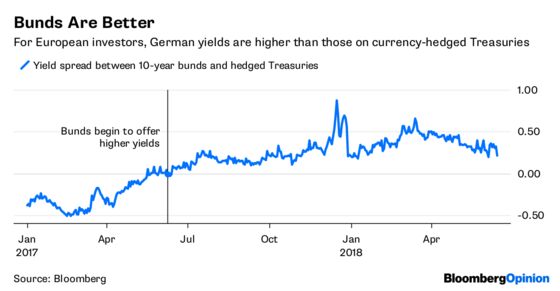

When looking back through history, there’s no denying that the current 10-year bund yield is low on an absolute basis. But, as the saying goes, everything is relative. And for the past 12 months, that German yield has been higher for euro-based investors than the 10-year U.S. yield, after hedging for currency risk.

That’s right: The 10-year Treasury yield, at 2.95 percent, is reduced to a measly 0.21 percent for Europeans after going through a hedging transaction called a cross-currency basis swap. While investors could buy U.S. bonds without protecting against currency swings, the wild move in foreign-exchange markets Thursday shows why traditionally risk-averse buyers want to avoid taking on that added volatility.

The math behind euro-based investors acquiring dollars to purchase U.S. Treasuries hinges on a few elements: the three-month London Interbank Offered Rate in each country, and the so-called cross-currency basis.

European investors pay dollar Libor (2.34 percent) and the basis (0.05 percent), while also effectively paying their local Libor because it’s negative (minus 0.32 percent). Even just eyeballing those costs, it’s clear the expense wipes out almost all of the 10-year Treasury yield. Suddenly, 0.43 percent on German bunds looks like a bona fide steal.

Anecdotes abound about how this dynamic is rippling across markets. Japan holds the least Treasuries since October 2011, even as the size of the market swells. Bloomberg News’s John Ainger reported last month that European insurers are also staying away, in part because of new regulations. UBS AG estimates that U.S. 10-year yields need to climb at least 30 basis points relative to German peers to become attractive. Achmea Investment Management BV said it requires spread widening more in the ballpark of 50 to 75 basis points.

Obviously, such a move would wreck Gross’s big trade.

“One of these days, and hopefully soon, that difference has got to be narrowed,” he said in a CNBC interview on Wednesday. “Investing requires patience. I think this is a trade that will work out.”

At least a few investors aren’t willing to wait. The unconstrained bond fund had $1.7 billion of assets at the end of May, down from $2.1 billion a month earlier, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. It has lost 2.94 percent in the past month and 3.71 percent over the past year, the data show.

Gross has put much of his own money into the fund, saying in a Bloomberg TV interview earlier this month that “my entire portfolio is on the line.” He called the press coverage of his bad day “ridiculous.” The net asset value of the fund has recovered, though at $9.04 it’s still below the $9.21 level from May 25, just before its steepest loss since inception.

The convergence that he envisions may yet play out. But after this week, divergence seems much more probable. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell was upbeat about the U.S. economy and is shifting the central bank out of its ultra-cautious mode. The ECB proved just the opposite, pledging to keep rates unchanged for longer than many anticipated to keep the markets sanguine about the end of its bond buying. Policy makers can’t go back on that now. By the time they consider raising their benchmark, the Fed might have hiked four or five more times.

It’s unclear what, if anything, will change the mind of Gross, who in April 2015 said bunds were “the short of a lifetime.” At the time, the 10-year German yield was about 0.1 percent.

But one thing’s for sure: whether you want to point to hawkish Powell versus dovish Draghi, or hedged Treasury yields, the idea that the U.S.-German yield spread “has to reverse,” as Gross said in his Bloomberg TV interview, just doesn’t seem to hold up.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.