Zambia Default Sets Tough Tone for Talks With Bondholders

Zambia Poised to Be First African Sovereign Default in Pandemic

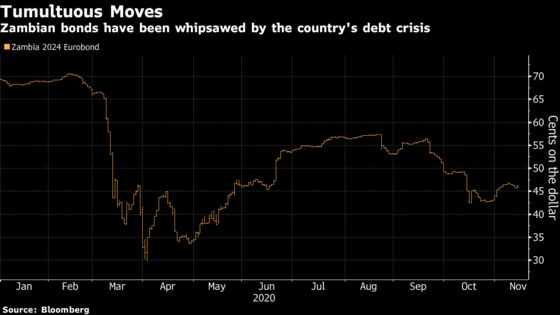

Zambia is squaring up for a bruising encounter with foreign bondholders after saying it can’t pay interest on one of its Eurobonds, making it Africa’s first sovereign default since the coronavirus pandemic struck.

A refusal by bond investors on Friday to grant debt relief to the government sets the tone for tough restructuring negotiations with a diverse range of creditors from pension funds in Europe to state-owned Chinese banks that Zambia owes almost $12 billion.

“A default could make an orderly and timely restructuring more challenging,” said Samir Gadio, head of Africa strategy at Standard Chartered Bank Plc in London. “A prolonged default may see some investors unwind non-performing bonds,” battering down prices that are already below half of face value, he said.

Holders of Zambia’s $3 billion of Eurobonds rejected a request to suspend interest payments for six months, and the grace period for an overdue $42.5 million coupon lapsed Friday, triggering a default.

That gives holders of all three securities the right to demand immediate repayment. While it’s unlikely they’ll take that route, Zambia could find itself locked out of international capital markets for years while it struggles to reduce its debt load and address fiscal challenges. General elections scheduled for August add another layer of complication.

“I would expect debt-restructuring talks for the Eurobonds to be very difficult and I would expect them to be protracted,” said Phillip Blackwood, adviser to Sydbank, which manages and advises portfolios with Zambia Eurobonds.

The default will make Zambia’s “financial conditions even tighter for a place where financial conditions have already been tight for quite a while,” said Gustavo Medeiros, deputy head of research at Ashmore Group, which holds Zambia’s dollar bonds. Local currency notes already have yields as high as 33%, and the kwacha has lost nearly half of its value against the dollar this year.

Equal Treatment

Zambia couched its request for an interest freeze as part of the Group of 20’s so-called Debt Servicing Standstill Initiative, an agreement between rich nations to suspend interest payments owed to them by poor countries. The government said it was asking all its foreign creditors, including private lenders, for the same relief.

China Development Bank last month agreed to defer interest payments. While that covered a small portion of the debt, it created a precedent that made it difficult to pay bondholders.

“The government is strongly committed to pursue a constructive and very transparent dialog with all its creditors,” Finance Minister Bwalya Ng’andu said Friday, adding that the state had no choice but to build arrears.

No Example

Bondholders, however, were concerned any relief they granted would be used to service debts to Chinese lenders, which account for more than a quarter of Zambia’s external liabilities. They also want more transparency and a credible economic recovery plan, preferably with the International Monetary Fund’s endorsement.

Other governments shouldn’t see Zambia as an example for how to approach debt restructuring, said Simon Quijano-Evans, an economist at Gemcorp Capital in London.

“Zambia can’t be used as a comparison to other countries, simply because it failed to approach the IMF over several years and failed to be transparent,” he said. “Other countries like Angola and Ghana did exactly the opposite and are thus in a much better position than Zambia.”

While the coronavirus pandemic added to Zambia’s woes, its debt problems started years earlier. The government borrowed heavily since 2012, ignoring warnings from the IMF of growing debt distress risks.

Some Eurobond investors, including Blackwood, argue that Zambia’s troubles only emerged in the years after it tapped international markets, and turned to China for funds. The nation sold its first dollar bond in 2012 and the last one in 2015.

“From Eurobond holders’ side, this is not about an unwillingness or otherwise to forgive debt,” he said. “It is clear to Eurobond holders that the debt problems escalated when the bilateral loans accelerated, after the Eurobonds were issued. The nature of those deals quickly caused problems for the country.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.