Yes, Market Moves Are More Extreme. But It’s Not the Apocalypse

Data show bigger moves more common but far from extraordinary.

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. stocks posted the strongest rally in eight months on Wednesday, just a few days after the largest Bitcoin slump since February. That followed the biggest crude-oil drop for three years. In October, tech shares had their worst day since 2011.

Yep, it’s been a banner season for superlatives -- and up until this week they had mostly been negative.

There’s a growing consensus that extreme moves point to a paradigm shift: A new era where the Federal Reserve is no longer propping up markets, growth is topping out, U.S. protectionism derails earnings and rising rates upend developing-nation economies.

Alternatively, people may just need to get some perspective. Turbulence in today’s markets is a blip compared to the past decade.

There’s evidence to suggest that, rather than being assailed by a brutal new era of big moves, investors have simply spent too long cosseted by low volatility and one-way markets. In psychological terms, it’s known as the recency bias. Traders got used to tranquility, making the current ride seem rougher than it is.

“This always tends to happen when you introduce some fear into the equation, and generally when the market goes south, people’s fear escalates,” said Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Leuthold Weeden Capital Management LLC. “Their time horizons shorten.”

‘New Regime’

Drilling down into U.S. stock swings lays bare this trap.

Sure, the headline stats look brutal, the bears vindicated. The S&P 500 Index has notched four declines of 3 percent in 2018, more than in the prior three years combined, and entered two corrections. The gauge has clocked two separate months where market value declined by more than $1 trillion, for the first time since 2008.

But context is key.

The graph below shows how fast very big days are piling up in the S&P 500. Technically, it’s a rolling tally of single-session swings that are twice the 12-month standard deviation. In other words, the frequency of big moves relative to all the other moves of the past year.

Instances of outsized swings are at the highest in at least a decade, underscoring what most investors are well aware of: Many more above-average gyrations have started happening. The VIX index, which uses options to show expected price swings for the S&P 500, also helps bear this out.

So far, so scary? Perhaps not.

The next chart shows the same data, but instead of using the one-year standard deviation to set the threshold of a significant move, it uses a 10-year measure. For a day to stand out under this lens, it has to be big not just by recent standards, but by historical ones. The recent swings barely register.

Translation: Yes, stocks have been posting larger moves of late. But on a longer timeframe, they’re not particularly extreme.

“Volatility we’ve experienced in the past few years was pretty low by historical standards, and it was suppressed by the coordinated easy monetary policies across the world,” said Alex Bellefleur, chief economist and strategist at Mackenzie Financial Corp.

“We’re slowly returning to a more normal volatility regime. It’s unlikely that we go back to the lows, but there’s nothing abnormal about that.”

Rejecting Recency

For macro investors, an important takeaway is that the patterns above are replicated to a greater or lesser extent across multiple assets, according to Bloomberg analysis.

These include tech stocks, equities across developed and emerging markets, commodities, developing-economy currencies and corporate bonds, U.S. high-yield debt and leveraged loans.

And for some assets, even moves relative to recent history have been pretty muted.

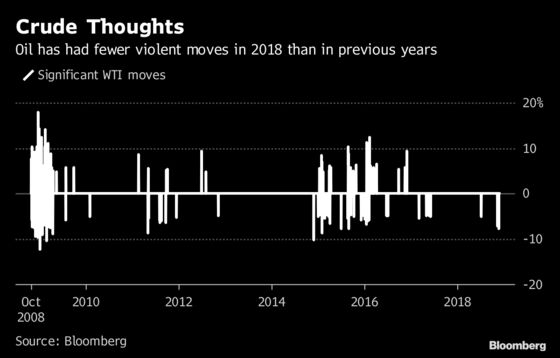

Despite all the hand-wringing over turmoil in the crude market in October and November, far more intense oil moves were registered in 2015. Back then, the Iranian nuclear deal, surging supply, falling demand and a strong dollar combined to almost halve the price of crude.

All this is not to say bigger price swings don’t matter. Idiosyncratic blow-ups can play havoc with the models used to manage risks by large investors. Meanwhile, the bears can point to the fact that, for most major assets, the trend is clearly toward more severe moves occurring.

That’s a message which won’t be lost on the Fed. At their latest gathering, policy makers showed they’re alert to the tightening financial conditions, noting the drop in equities, strengthening dollar and rising yields.

Yet in what amounts to a tacit rejection of recency bias, a number of members judged financial conditions remained accommodative “relative to historical norms,” minutes of the meeting said.

‘High-Strung’

Regardless, investors are hyper-sensitive to headline risk as they grapple with political dramas, a maturing business cycle and a year in which most consensus trades got killed. It’s a big reason the S&P 500 surged after a dovish tweak to communication from Fed Chair Jerome Powell on Wednesday.

“Markets participants are more high-strung amid the downturn in global equities, credit, EM and commodities,” Alvin Tan, a director of FX strategies at Societe Generale in London, wrote in a note to clients this week. “Tape bombs can shake things up in this febrile atmosphere, at least temporarily.”

--With assistance from Sarah Ponczek, Elena Popina and Luke Kawa.

To contact the reporters on this story: Samuel Potter in London at spotter33@bloomberg.net;Eddie van der Walt in London at evanderwalt@bloomberg.net;Vildana Hajric in New York at vhajric1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Samuel Potter at spotter33@bloomberg.net, Sid Verma, Cecile Gutscher

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.