Why China’s Starting to Shake Up Interest Rates

The PBOC has recently preferred to try to let the financial sector play a bigger role as the middleman to raise money.

(Bloomberg) -- The People’s Bank of China is liberalizing its interest-rate system in another milestone in landmark reforms started four decades ago to boost the role of markets in the economy. The overhaul might help lower the cost of borrowing for companies and households in the short term, as the U.S.-China trade war and domestic forces weigh on the economy.

1. How did it work before?

Most central banks govern the price of money in an economy via the rate that banks are charged to borrow cash over short time periods. In China, that approach had been divided into two steps. First, the PBOC guided prices for funding in the interbank market via its reverse repurchase agreements and medium-term lending facility. Then, it set the benchmark rates that were used to price mortgages, business loans and other commercial lending -- the one-year and five-year lending rates. That was a relic of the command economy and the PBOC wanted to change it.

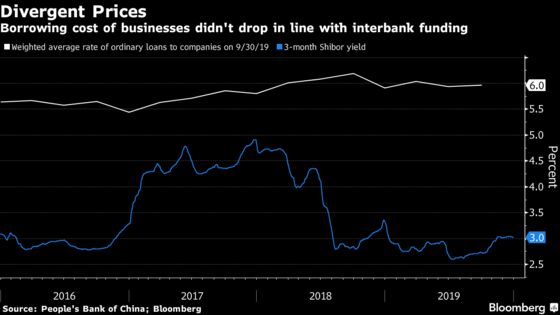

2. What was the problem?

The one-year rate is too blunt a tool for a modernizing economy that’s got a problem with excess debt. Cutting it slashes borrowing costs everywhere and risks fueling property and financial bubbles. Raising it risks choking growth and throwing borrowers into distress. The PBOC wants the financial sector to play a bigger role as the middleman for channeling money to enterprises in need. To that end, the central bank provided more and cheaper funding to banks to help bring down inter-bank rates -- a move intended to reduce the cost of loans to enterprises and households. That didn’t happen, however, partly because the two-track system blocks the rates banks pay from being freely passed on to the public.

3. How does the new system work?

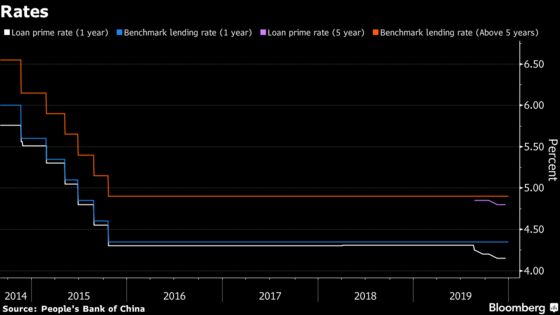

Starting in August, the PBOC replaced the benchmark lending rate with two new reference rates for bank loans, to be announced on the 20th of each month. Most of the new and existing loans will be priced with reference to the new system by August 2020, effectively scrapping the old one-year benchmark.

- The new loan prime rate, or LPR, is based on the interest rate for one-year loans that 18 banks offer their best customers. The banks submit the rate each month in the form of a spread over the interest rate of the PBOC’s medium-term loans. The intention is that banks mainly use this LPR as the basis for loans to households and businesses. It is set lower than the old benchmark rates and is expected to continue falling in 2020.

- The PBOC also introduced a LPR for loans longer than five years, accompanied by mortgage rules to safeguard against a massive expansion in home loans that could fuel another property boom. (China has seen a few.)

- PBOC Governor Yi Gang has said the benchmark deposit rate -- the interest banks offer to households or companies for deposits -- will be kept in place for now.

- Outstanding loans will be converted from the old benchmark to the new one in 2020, between March and August. Banks will have to negotiate with clients on the pricing -- how many basis points to add or cut. While home mortgages will also be converted, the new borrowing cost must remain the same to “reflect the request to regulate the property market,” the central bank said. They can be repriced starting in 2021 at the earliest, and any adjustments after that must be at least a year apart.

4. How do other central banks do it?

Eventually, the PBOC wants to influence the economy and financial markets via the price of its short-term loans in the open market -- an approach similar to other central banks. The Federal Reserve targets the cost of short-term interbank loans to control borrowing costs in the broader economy, raising it or lowering it to affect the cost of loans for homes, businesses and financial products. The Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of England have similar policies. In recent years, however, the policy-setting tools of global central banks have become more complex, with the advent of quantitative easing and negative rates in Japan, the European Union and elsewhere.

5. What are the difficulties?

China’s $45 trillion financial sector is mainly composed of banks, with two-thirds of the country’s financing provided through bank loans. When borrowing costs fall, policy makers will have to be on their guard for housing and stock market bubbles. Regulators will also need to ensure there are enough derivative products linked to the LPR to help hedge risks. Some 18.6 billion yuan ($2.6 billion) worth of LPR-based interest rate swaps were signed in August, the most since authorities started publishing the data in 2016.

6. How will we know if it’s working?

If all goes to plan and bank loans are increasingly priced with reference to the LPR, lending rates will fall and economic growth will get a boost. In practice, the cost of implementing such profound reforms could offset the benefits. Banks also may still see lending to state firms and local governments as safer bets than to small and private companies.

7. And the bottom line for banks?

Overhauling interest rates is a potential threat to bank profitability and the well-being of the banking sector. The government’s policy goals for 2019 included banks increasing lending to small firms by 30%, and for the average lending rate to be 1 percentage point lower than in 2018. Banks may have to bear some of the cost, and their net interest margin will probably decline. Banks also have to convert some of the 152 trillion yuan in outstanding loans to the new benchmark, which could squeeze profits further. On the other hand, banks stand to earn more if the changes stimulate demand. And borrowers could save nearly 50 billion yuan in interest payments from March to August, according to Huachuang Securities Co.

The Reference Shelf

- PBOC announcement of the new system and a Q&A about how it will work.

- What the U.S. Federal Reserve’s rate-cut signal means for China.

- Additional QuickTakes on China’s evolving monetary policy toolkit, its digital currency ambitions, and why its economy slowing to 6% matters for the rest of the world.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Daniel Moss says the PBOC shouldn’t follow the Fed’s path, Andy Mukherjee looks at the digital plans, and Nisha Gopalan sees a grim year for M&A.

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Yinan Zhao in Beijing at yzhao300@bloomberg.net;Tian Chen in Hong Kong at tchen259@bloomberg.net;Jing Zhao in Beijing at jzhao231@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeffrey Black at jblack25@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg