When Bonds Attack: Stock Valuations in a Rising Rate Environment

When Bonds Attack: Stock Valuations in a Rising Rate Environment

(Bloomberg) -- There’s no magic number, no button that gets pushed by Treasury traders that blows up equities. But as was demonstrated again by last week’s downdraft, pressure points can crop up in the interplay of the two markets that bear watching if you own stocks.

One relates to the partially hidden, not universally accepted, always-shifting relationship between bond yields and corporate earnings, a version of something known, sometimes, as the Fed model. Three times in 2018 it’s shown stocks getting to a particularly expensive point versus fixed income. And three times stocks have sold off.

Maybe it’s coincidence. The comparison doesn’t claim to be scientifically precise. And it’s hard to imagine it being a conscious obsession of equity owners coping with everything from Donald Trump’s trade war to surging oil prices. But as a way of gauging when signals from credit markets turn troublesome -- of understanding why “bond yields” get blamed for zapping equities -- you could do worse.

“It’s a purely rational mathematical response,” said Brad McMillan, chief investment officer for Commonwealth Financial Network, which oversees $156 billion. “When 10-year yields go up, the required return for everything else has to go up as well. And that means prices go down.”

Down they have gone, with the S&P 500 sliding 4.1 percent last week, the most since March. But with markets steady Monday and Tuesday, the selloff is looking more like a valuation adjustment -- a painful one -- than an instance of stocks divining a more dire message on growth or inflation from bonds.

A host of other factors are at play when bonds and stocks clash, among them the economic signals the two markets send each other and whether gains in one mitigate losses in the other. Still, the concept of relative value is usually in the background when people wonder about the staying power of the bull market in equities, by some measures the longest in history.

The model hit a relatively extreme reading into October, when 10-year Treasury rates surged and the S&P 500 began a tumble that over 11 days was worse than any full-month decline in seven years. More than $1 trillion of equity value was erased as tech stocks saw some of their worst selling since 2011.

At the simplest level, bond yields influence stock prices by offering a competing return. Anyone buying a Treasury at the start of last week was locking in 3.23 percent annually for 10 years. The question for investors becomes whether gains in shares will exceed that by enough to offset all the bouncing around they’ll do over the next decade.

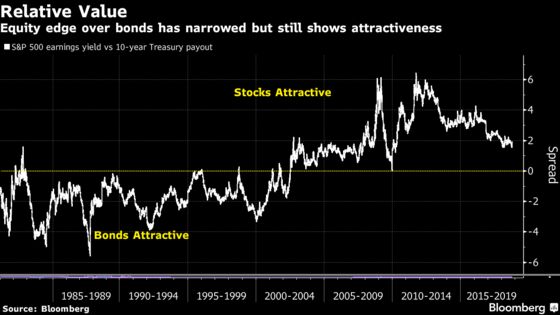

To make this call, analysts sometimes look at how much a stock “pays” in earnings, expressing it as a percentage of price and comparing it to the Treasury yield. On this basis, the S&P 500 pays about 5 percent in annual profit, comfortably above the 3.16 percent offered in 10-year Treasuries. Go back a week, though, and the gap was narrower -- only about 1.6 percentage points. Stock market routs in February and March began at roughly the same spot.

Note that the comparison gets less favorable when stocks rise or bonds fall -- it’s a valuation case. For adherents, this explains why a group like tech stocks trading at nosebleed multiples are more exposed to rising rates than the rest of the market. The Nasdaq 100, home to Apple, Facebook and Alphabet, saw its earnings yield slip as low as 3.8 percent before this week’s rout began. That was about half a percentage point more than fixed-income paid.

The comparison isn’t unanimously embraced by professionals. While viewed by many as a handy way of gauging relative value, corporate earnings and bond yields aren’t the same -- they move with different volatility and different sensitivity to inflation.

Even Ed Yardeni, the economist who coined the term “Fed Model” from a July 1997 report by the central bank, acknowledged its limitation given the Fed’s heavy involvement in setting interest rates nowadays.

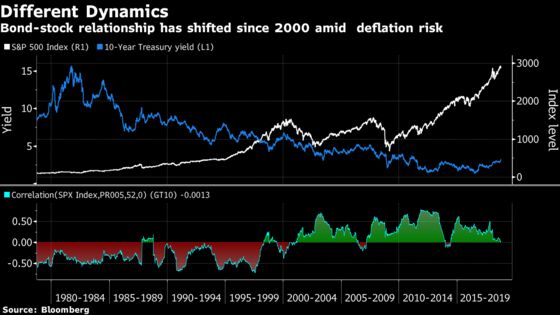

“The relationship worked very well prior to 2000. Not so well since then, as bond yields have been held down by the central bank,” said Yardeni, founder of his namesake research firm. “But it doesn’t mean interest rates don’t have any impact on stock prices, as we’ve seen recently.”

If you look at history since 2000, the bond comparison has a spotty record. Stocks appeared to be relatively cheap going back that far, yet equities also suffered one of the worst bear markets in history from 2007 to 2009.

Over the stretch, when yields rose, stocks also tended to rise, rather than falling as the Fed model would suggest. The pattern exists because deflation has dominated market concerns and therefore higher rates have been greeted as a bullish sign for growth by equity investors, according to Ned Davis Research.

That’s not to say that the model is broken. From the 1970s to 1990s, the relationship between the two assets played out just like it would have envisioned. And that’s because at that time, inflationary forces prevailed and higher yields tended to lead to lower share prices for fear of Fed tightening.

After this month’s concerted selloff in bonds and equities, the pressing question for investors is: has the market entered a new regime where higher rates hurt stocks?

It’s too early to worry about that, according to Goldman Sachs strategists including Peter Oppenheimer. While the decline in the S&P 500 reflected an adjustment to the quick increase in bond yields, at 3.2 percent, the level of 10-year Treasury yields is far from the 4 percent or 5 percent that has historically damaged equities, they said.

Thanks to the Fed’s efforts to keep interest rates at rock-bottom lows, income generated by S&P 500 companies hasn’t fallen below Treasury rates for 16 years. While the current advantage for stocks sat near its least bullish level since 2010, it’s still generous compared with the previous two decades, when equity valuations rarely beat bonds.

“If Treasury yields were to rise, that wouldn’t be inconsistent with where equity yields are,” said Brad Neuman, director of market strategy at Alger, which oversees $28 billion in New York. “Stock valuations are somewhat higher than history, but are reasonable relative to interest rates. We don’t see big catastrophe from higher bond yields.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Lu Wang in New York at lwang8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.