There’s No Path to a Fast Recovery in Venezuelan Oil

There’s No Path to a Fast Recovery in Venezuelan Oil

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The longest a human has held their breath is 24 minutes and 3.45 seconds, according to Guinness World Records. Even if every minute were three months, Venezuela’s oil industry won’t be back on its feet by the time you have to come up for air, no matter how the current political chaos plays out.

I’m not going to try to pretend I know how the situation in Venezuela will evolve over the coming days, weeks or months. Almost anything could happen: the quick ouster of President Nicolas Maduro; a protracted period of civil unrest; or the current regime digging in with the support of the military.

One thing I am fairly sure of, though, is that the damage inflicted on the country’s oil sector by years of under-investment and mismanagement, compounded by the exodus of large parts of the skilled workforce, will not be quickly, or easily, reversed. And it won’t matter who is in power, or how any transition comes about.

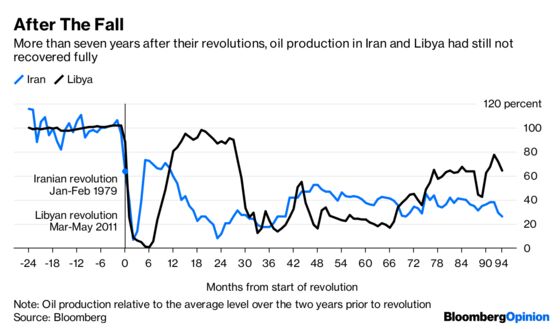

If you want a quick comparison of how things might evolve in the Venezuelan oil sector in the coming years, look no further than Libya’s recent past, or Iran’s experience after the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

In both cases there was an immediate slump in production to near zero, followed by a brief recovery, then years of a slow grind, with output levels around half what they had been before the revolutions. Seven years after the toppling of the previous regimes, output had still not recovered fully.

While there are differences between the situations in each of the three countries, there are similarities too. Iran’s oil industry was heavily politicized by the post-revolution government, with technocrats purged and replaced by political appointees with little, or no, industry experience. In Venezuela that has already happened. President Hugo Chavez purged technocrats who were critical of his socialist revolution. His successor, Maduro, installed Major General Manuel Quevedo, a military man with no industry expertise, to run the state oil company and simultaneously head the country’s oil ministry in 2017.

In Libya, competing local militias and a breakdown of government control over large parts of the country have hampered the recovery. Theft, hostage-taking and closure of pipelines and production facilities continue to delay rehabilitation of oil field and transportation infrastructure. Storage tanks have been destroyed and inward investment remains a trickle. While that kind of lawlessness hasn’t yet affected Venezuela, the country’s oil infrastructure is crumbling.

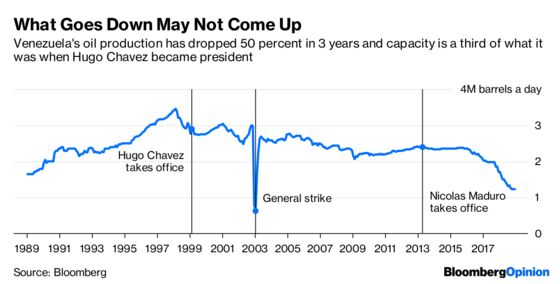

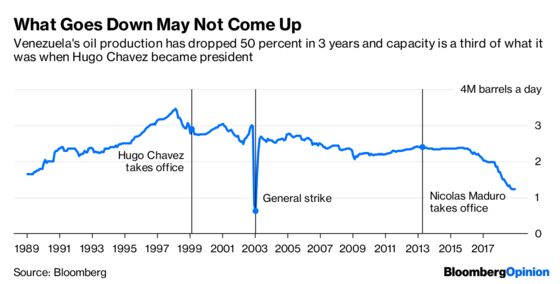

Venezuela has a mountain to climb to restore its oil industry to its former glory.

When Luis Giusti resigned as president of state oil company Petroleos de Venezuela the day before Chavez took office, in February 1999, the company he had headed for nearly five years was the envy of the rest of OPEC. It boasted production capacity of about 3.3 million barrels a day, up nearly 30 percent since the start of 1994. It had a network of overseas refineries to secure market access and was in the process of building two cokers at its domestic refineries to boost the production of high-value products from its heavy crudes. The parts of Venezuela’s vast portfolio of reserves that were not core to its operations had been opened up to foreign and domestic investors, and there were credible plans to lift production capacity as high as 6 million barrels a day.

Today, its production is roughly a third of what it was when Chavez took power. PDVSA’s overseas refineries have mostly gone and its domestic plants are running at as little as 20 percent of capacity. The joint ventures developing the heavy oil projects in the Orinoco Belt have, for the most part, failed to build the expensive upgraders required to meet ambitious output targets. They instead rely on blending smaller volumes of the tar-like crude they produce with lighter oil — itself occasionally imported from as far away as Algeria — to allow it to flow through pipelines to export terminals on the coast. That investment may pick up under more benign conditions, but even so it will take several years to bear fruit.

It will take more than just opening some taps to let the oil flow again. Cracked pipes, busted valves and worn gaskets have left a legacy of toxic spills. Much of that infrastructure may need to be replaced before production can increase.

The country’s older oil fields in and around Lake Maracaibo in the west of the country need constant supervision, but the engineers who understand the reservoirs have largely left, taking up jobs in neighboring countries, the U.S. or Canada. A change of government is only the start of what will be needed to bring them flooding back.

Giusti, who trained as a petroleum engineer, told me several months ago that he worries that there may also have been irreversible damage to the oil reservoirs in Maracaibo, and that production in western Venezuela may never recover.

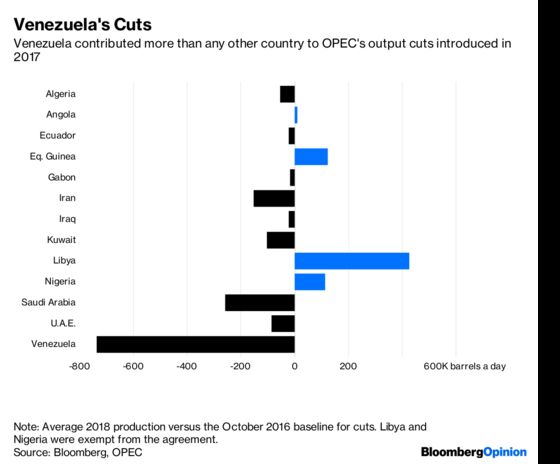

The collapse in Venezuela’s production over the past two years was a major part of the OPEC+ group’s success in cutting supply. It shouldn’t worry too much about a rapid rebound.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.