Vanishing Spreads Are Ringing Alarms in Risky Debt Markets

Vanishing Spreads Are Ringing Alarms in Risky Debt Markets

(Bloomberg) -- It’s rarely been a better time for borrowers with good credit to tap into the bond market. In fact, the same is true for borrowers with dodgy credit.

It’s not just U.S. Treasuries that are seeing near-historic low yields. Once-radioactive sovereign markets like Greece, high-tax U.S. states like New York and California, and corporate borrowers from investment grade to junk are being rewarded with yields that are barely above benchmarks.

With the record-long U.S. economic expansion on course to enter a 12th year, a swollen supply of investor capital flooding into markets is shrinking or eliminating risk premiums throughout the fixed-income landscape. It’s not that investors are oblivious to the eye-popping valuations. In fact, “bond bubble pops” was the second-most-cited risk in Bank of America’s latest survey of fund managers. Regardless, many investors ask, what choice do they have but to keep on buying?

“Things are frothy right now,” said Jude Driscoll, head of public fixed income at MetLife Investment Management, which oversees $586 billion in assets. “Risk assets are definitely priced at the tight end. In what world would you lend money to some of the profiles in high yield at 4%? That doesn’t make any sense to me from a historical basis. People are getting in because they don’t want to miss out.”

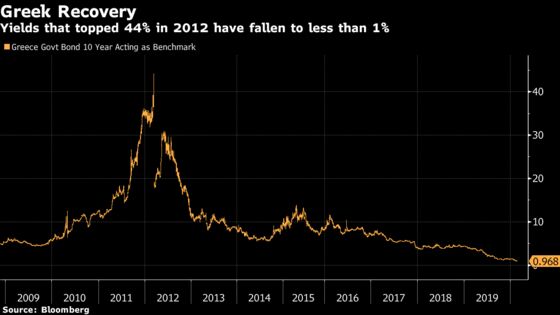

Sovereign bonds from some of the most-indebted European nations highlight how far the situation has gone. Ten-year Greek bond yields topped 44% at the height of the nation’s financial crisis in 2012. These days, they yield less than 1% and the spread above negative-yielding bunds is about 140 basis points. That’s near the narrowest since 2009, just before the country was thrown into a multiyear crisis that brought it to the brink of default. Italian 10-year yields have fallen from 7.49% in 2011 to less than 1% these days. Ireland’s 30-year rate reached an all-time low of 0.61% today. Even Ukraine, which skirted a default five years ago, has seen its sovereign yields drop to record lows.

Even though they may not be priced in, risks are increasing. Countries and companies are already reducing their expectations for how productive they’ll be in light of the spreading coronavirus, with Singapore planning its biggest budget gap in more than two decades, while Apple Inc. has warned it won’t meet sales expectations.

In credit, Kraft Heinz Co. became the largest fallen angel of the current cycle last week, losing two investment-grade ratings. Macy’s Inc. and Renault SA also just received their first high-yield ratings, reigniting fears that a slowing economy could tip more companies over the edge. UBS Group AG strategists led by Matthew Mish predict there could be as much as $90 billion of investment-grade debt downgraded to high yield this year, dwarfing a two-decade low set last year at just under $22 billion.

“It’s been a resumed search for yield, with Greece and Italy along for the ride,” said Richard Kelly, head of global strategy at Toronto-Dominion Bank in London. “You have less fears of systemic issues from the virus, but more acceptance that this means growth and inflation should be lower for longer.”

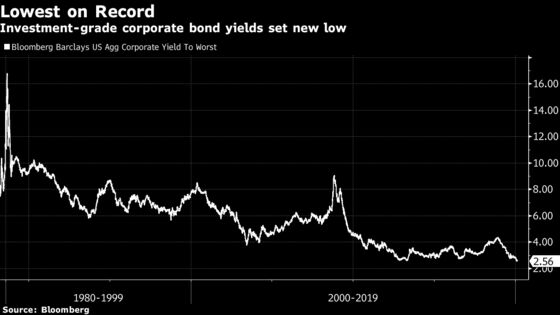

The hunt for yield shows no sign of slowing down, so rates and spreads may decline further. Flows into fixed-income assets nearly doubled last year to $1 trillion, according to data from Morningstar Inc., and bond funds are on track to exceed that amount this year. U.S. corporate investment-grade borrowing costs have never been lower, while high-yield rates are close to their lows.

Even heavy issuance of corporate debt and Treasuries may not be enough to meet investor demand. While more than $1 trillion of investment-grade credit is expected to be issued this year, gross supply is forecast to be down slightly and net supply will be almost 40% lower than it was in 2019, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. All else equal, that should drive spreads even tighter, especially as high-grade funds continue to reap inflows from investors seeking income assets amid $13 trillion of negative yielding debt, Western Asset Management portfolio manager Kurt Halvorson said in a Feb. 13 blog post.

Companies have taken advantage of investor appetite to refinance debt, with some high-yield issuers like HCA Inc. and Post Holdings managing to set record-low coupons for their respective ratings and maturities last week. Exuberance in the high-yield market is letting even some of the lowest-rated issuers sell new debt. Husky Injection Molding sold a rare pay-in-kind toggle bond last week to fund a dividend to its private equity owner. So-called PIK notes are particularly risky because they give companies the option to defer interest payments.

Elsewhere in the junk markets, Zayo Group Holdings Inc. is shopping $2.58 billion of high-yield bonds to fund part of its leveraged buyout. The planned debt package includes $1 billion of unsecured CCC+ rated notes being marketed to investors at a yield of around 6.25%, well below the 10% average level for debt rated that deeply into junk.

Investment-grade companies are reaping the benefits as well, with deals from cuspy credits many times oversubscribed, often resulting in lower borrowing costs. FirstEnergy Corp. tapped the market Tuesday for the first time since spinning off its bankrupt subsidiary at a record low rate. Deutsche Bank sold a perpetual AT1 bond last week, the riskiest form of bank debt. It borrowed $1.25 billion at a 6% rate, lowering its funding costs by 75 basis points, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the peak, investors had placed orders more than 11 times the offering size.

Alarm bells are ringing. The BofA fund-manager survey found that owning U.S. Treasuries and investment-grade corporate bonds were considered the second- and third-most crowded trades, respectively, after U.S. technology and growth stocks. Its strategists have recommended owning less high-grade bonds as valuations are too tight. Still, what else is a fixed-income investor supposed to do but hunt for yield?

“What do you do with your cash?” said Luke Hickmore, investment director at Aberdeen Standard Investments in Edinburgh, where he helps run a number of bond funds. “Leaving it standing there makes no sense and the experience over the last 10 years is that there is no pain in buying bonds. Learnt behavior is that it is safe. Inflation is nowhere and central banks start buying every time yields go higher.”

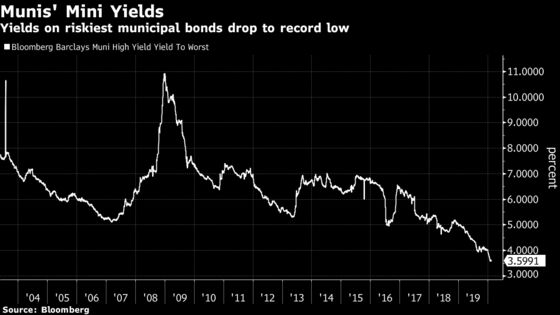

Heavy demand for tax-exempt income drove yields on even the riskiest municipal bonds to 3.58% on Friday, the lowest since Bloomberg’s records began in 2003. The influx has compressed spreads across the country and caused some debt in high-tax states like California and New York to yield less than top-rated benchmark securities. Municipal mutual funds have reported inflows for the 58th straight week on Feb. 13.

Investors keep adding to municipal bonds amid concerns about potential volatility in the equity market, according to Nisha Patel, a director of portfolio management at Parametric Portfolio Associates, which offers separately-managed accounts.

“Even at these yields, we hear all the time from advisers and clients that, ‘I don’t want to buy bonds,” she said at a Bloomberg News panel last week, “but I have to.”

--With assistance from Danielle Moran.

To contact the reporters on this story: Molly Smith in New York at msmith604@bloomberg.net;Claire Boston in New York at cboston6@bloomberg.net;John Ainger in London at jainger@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at ngammeltoft@bloomberg.net, Michael P. Regan, Jenny Paris

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.