Trump Trade Czar Eyes Exit Hailing Tariff Power His Critics Hate

Trump Trade Czar Eyes Exit Hailing Tariff Power His Critics Hate

(Bloomberg) -- Robert Lighthizer has built a career on being a wily contrarian.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that President Donald Trump’s trade czar is going out tilting at a consensus among mainstream economists that Trump’s signature policies -- his tariffs on billions in imports from China and steel from around the world -- have been a failure by most metrics.

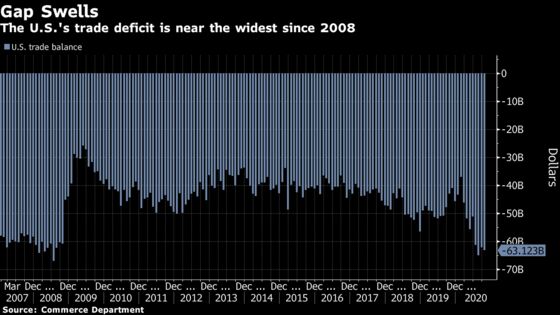

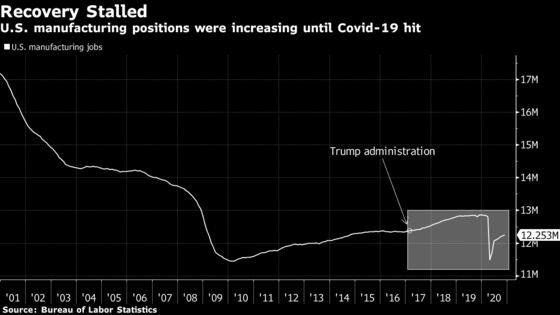

The U.S. is on track to end Trump’s presidency and a pandemic-affected 2020 with a trade deficit in goods and services larger than the one he inherited, Lighthizer’s critics point out. At least 100,000 fewer Americans were employed in manufacturing in November than at the start of Trump’s presidency.

Yet the U.S. trade representative, who is preparing to leave office in January believing he has overseen a sea change in American trade policy, particularly toward China, sees a different storyline borne out by the data.

Strip away the impact of this year’s pandemic, Lighthizer argues, and it’s clear the Trump trade doctrine has delivered. Five of the six quarters prior to the pandemic saw decreases in the U.S. goods and services deficit, he points out, though in the eight prior to that the trend went the other way. Before Covid-19 hit the economy in February, he adds, the U.S. had gained more than 500,000 manufacturing jobs on Trump’s watch.

Most importantly, though, those changes had translated into higher wages for American workers with the median household income in 2019 rising 6.8% from the year before.

“That’s the highest in American history,” Lighthizer said in an interview.

It may frustrate his critics but Lighthizer’s pushback is evidence that, as in its other forms, Trumpism’s trade legacy may be an enduring one.

President-elect Joe Biden and his aides have already signaled that in part by vowing a pro-worker focus as they rebuild the U.S. economy and a trade policy that will be a component of what they are dubbing a “foreign policy for the middle class.” Though what that means in substance remains unclear.

More clear is that Trump’s protectionist episode and the support it garnered him again in key industrial states like Ohio this year are likely to continue encouraging the Democratic Party’s own trade skeptics and progressives. Which is why the battle over the economics of Trump’s trade legacy matters and will shadow the work of Lighthizer’s likely successor, Katherine Tai, the senior congressional staffer Biden has chosen for the role.

It is in many ways a theological battle. Adam Posen, the head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, which has led the analytical charge against Trump’s trade policies since 2016, likens any statistical defense of them to those offered by climate change deniers, or vaccine skeptics. To critics like Posen, Trump and Lighthizer’s preferred tool -- the tariff, or import tax -- has just gone through a very public discrediting experiment.

To Lighthizer and his supporters, however, the mighty American tariff has finally been absolved of what protectionists have long argued has been the unfair taint hanging over them since the Smoot-Hawley era of the 1930s, which economists have long blamed for at least prolonging the Great Depression around the world.

Lighthizer argues none of the critics’ predictions of economic or financial market collapses and price surges that accompanied the rollout of Trump’s tariffs in 2018 and 2019 have materialized. “It’s an important lesson that these catastrophes that they predicted didn’t happen,” he says.

Nor have the steel tariffs that critics have pointed to as one cause in the industrial output recession that the U.S. suffered in 2019 really hurt manufacturers, he argues.

Manufacturing jobs grew most robustly in 2018 when the tariffs first went in place and steel prices rose, he points out. And conversely that jobs growth slowed as steel prices fell in 2019. To Lighthizer, that is proof that a rescue effort for an essential industry could be done without major economic disruption.

“You have to have a steel industry,” Lighthizer says. “There is literally no evidence to support this notion that introducing the tariffs had a negative impact on manufacturing.”

Critics would argue the slump in steel prices that followed the initial spike and the softening manufacturing jobs market and industrial output in 2019 were evidence of an impact on demand. Prices rose and demand fell in response. Which meant that by the end of 2019 even U.S. Steel Corp. was announcing layoffs.

The tariffs levied on imports from China worth some $370 billion before they went into place have also had no negative economic effect, Lighthizer insists, despite credible studies pointing to the opposite.

Lighthizer contends the tariffs together with a “Phase One” trade deal signed with Beijing in January have helped rebalance trade with China and been part of an effective pressure campaign to shift supply chains out of China.

“The administration’s policy has put tariffs on things that they had taken advantage of us on. It has helped to block their anti-market industrial policy. It has done all of these things. Without question it has changed the nature and it has set up rules which no one else had done before,” Lighthizer said.

Lofty Promises

The deal he negotiated with China is often derided by critics as a dressed-up collection of unrealistic purchase commitments that Beijing has yet to live up to. It also failed to address fundamental issues like Chinese industrial subsidies.

Yet Lighthizer and his supporters argue the more important components include a mechanism to deal with bilateral economic disputes and new Chinese commitments on intellectual property. It guarantees greater access for U.S. financial services companies to the Chinese market. Its currency rules may prove important in the future. Beyond the commitment to buy more U.S. agricultural exports by Beijing were real changes in the regulatory barriers to those farm products, Lighthizer says.

“And they’ve implemented almost all of it,” he says.

The Trump administration has helped usher in an awakening around the world to the threat posed by China and its economic model, Lighthizer says, though he conceded that China’s own behavior in recent years has contributed to that.

The mainstream view before the Trump administration, Lighthizer says, was that “China was a force for good in the trade world. And that’s completely changed not only here but in Europe and Africa and South America.”

Had Trump won the November election and were Lighthizer staying on he would be continuing to press for change in the relationship with China. Lighthizer believes the Biden administration should use the leverage it has from the existing tariffs to build on Trump’s trade deal and avoid a return to the endless and usually ineffective “dialogues” that prior administrations got caught up in.

U.K. Negotiations

Lighthizer believes he might have been able to close a deal with the U.K. before a congressional deadline next year. But he is also not convinced about the economic value of such a deal. His U.K. counterparts seem to want a deal for other reasons including a validation of their post-Brexit place in the world.

Were he to continue in office Lighthizer also would be turning his spotlight to a growing trade deficit with the European Union, one driven largely by automobiles. And to the World Trade Organization, to which he still attributes many of the failings in the global trading system.

Lighthizer is now in discussions with his EU counterpart, Valdis Dombrovskis, over a possible solution to a long-running trade fight over subsidies provided to Airbus SE and Boeing Co. that has led to a new round of WTO-authorized trans-Atlantic tariffs.

But Lighthizer’s complaint is that the WTO system now often results in few substantial changes in practice.

That fits into the broader context of a discussion over new rules curtailing industrial subsidies -- and China’s in particular -- that many trade policy makers would like to see the WTO have. For now, Lighthizer says, the WTO is like a laughably ineffective on that front and the Airbus case is an example of it. He remains convinced some European governments will continue to find ways to subsidize Airbus as it competes with Boeing and wants to see countries like France and Germany forced to pay some sort of compensation.

‘Robbing Your Garage’

“It literally is like somebody is robbing your house,” Lighthizer says. “You go to court and have them stop robbing your house and they start robbing your garage.”

His skepticism is what drove a U.S. war on the institution’s appellate body, which Lighthizer crippled by blocking the appointment of new judges. He’d like to see a system of one-off arbitration instead and argues the appeals process until now has removed any incentive to negotiate new rules.

He also has flagged his desire to see the WTO engage in a global renegotiation of its members’ tariff schedules. Too many large developing economies benefit from high tariff walls negotiated when they first joined the institution, he says.

The answer for Lighthizer is a universal tariff level, a 10% flat tax for trade if you will. With a bit of wiggle room allowed for “some small amount of your goods because you have political reasons.”

Which really comes back to Lighthizer’s belief in the power of tariffs, the one that irritates his critics and economists most. The cure is simple, Lighthizer said: “Everyone ought to have the same tariffs.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.