There’s the Legend of Paul Volcker and the Man I Got to Know

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has described his own initial encounter with Paul back in the early 1990s.

(Bloomberg) -- One evening about two years ago, I was at Paul Volcker’s Manhattan apartment when the phone rang. It was Ray Dalio, the billionaire hedge fund manager, inviting Paul and his wife, Anke, to join him at the ballet on some future date. Soon after, Paul said that he and Anke had to leave for Brooklyn. They were attending a wake for his barber.

I walked home that evening, as I did after every meeting as we worked on his memoir, thinking about what a truly remarkable man he was. Of course, he was best known for his great public accomplishments: He was the point man at the Treasury Department in 1971 who managed the dollar’s untethering from gold; he quelled the double-digit inflation that took root in the U.S. in the late 1970s; he helped guide the country’s response to the 2008 financial crisis.

But what struck me, again and again, was how he treated people.

In the last three years of his life, I had the privilege of getting to spend time with him. A publisher had recruited me to help him write his memoir. The idea was that I would interview him at his home and office over the course of a few months and somehow shape the transcripts into a narrative. That wasn’t quite what happened.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has described his own initial encounter with Paul back in the early 1990s, just a few years after Volcker’s eight-year tenure as chairman. “I was frightened of even meeting him, I was so intimidated by this global figure,” Powell said. “And he couldn’t have been nicer and more interested in helping me and supporting me.”

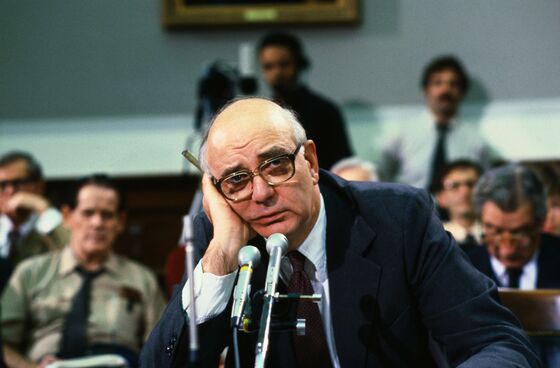

That was my experience, too. At 6-feet, 7-inches, with a world-famous scowl, Paul could be a forbidding presence. I was anxious when I went to his Rockefeller Center office for the first time, braced for stern questioning or withering judgment. So the surprise was how much he smiled, and how as he told stories, he chuckled -- a lot.

He took me on without hesitation, and gave me some homework: A copy of “Changing Fortunes,” his 1992 book with Toyoo Gyohten, and a set of compact discs with hours of interviews he’d conducted for the Federal Reserve’s oral history project. He didn’t tell me to read the three biographies -- William Silber’s from 2012, Joseph B. Treaster’s from 2004, and William R. Neikirk’s from 1987 -- but of course I did.

With so much already out there, why write a memoir? It was the summer of 2017. A few years earlier, he had founded the Volcker Alliance to help make government more effective. The biographies were tuned to particular episodes: his role in severing the dollar’s link to gold; his conquest of inflation; the management of financial crises. This book would cover all of that, briefly, but focus on his life’s true mission, which was creating a civil service so competent and responsive that it could restore the public’s trust in government.

That was a calling he had inherited from his father, an engineer who became the first non-partisan town manager in New Jersey, in Cape May and then in Teaneck. Paul revered his father, and told stories about his heroic feats. When local politicians tried to meddle, Paul Sr. took them to court and won. He served as the town engineer for free, and cut his own pay during the Depression. He made Teaneck famous as the lowest-crime town in America. It was picked as the U.S. Army’s model for occupied countries after World War II.

His son lived up to that example -- on a global stage.

His mother made an impact, too. In his office, Paul kept a framed copy of a letter, dated Nov. 15, 1929, about two weeks after Black Tuesday, that she had written to her own mother. It reads, in part:

“As for what I think of the stock markets, I haven’t bothered much about it. I have expected a drop from the inflated values for a long while and while most stocks are below their real values now the pendulum will undoubtedly swing back to normal again. Of course people who bought on margin mostly got stung. Gambler’s luck, and anyone is foolish to gamble if he’s using money he needs for it.”

Not a long way from that last sentence to the Volcker Rule!

During our interviews, Paul often defied my expectations. He had criticized the high bonuses and trading-centric culture of firms like Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which he thought undermined any focus on their customers. So when President Donald Trump was said to be considering naming former Goldman Sachs executive Gary Cohn as Fed chairman, I was surprised that Paul approved. The Fed relied too much on academic economists; it needed someone with Wall Street experience, he said.

Another time, I asked for his view of Modern Monetary Theory, which posits that a government with its own central bank and currency can and should keep spending until the economy is running at full employment. Surely the greatest living inflation fighter would recoil at such a prospect? But instead he simply pointed out that MMT hadn’t really been tested.

It wasn’t just his thinking that was surprising. At 90, Paul was still taking the bus to the office and back home, always happy when strangers recognized him and said hello. He relished spending time with people from all walks of life.

One day, Paul handed me a sheaf of pages he’d written: an initial draft of a preface. He was recovering from an operation, had some down time and had started writing. I encouraged him to continue. His assistant, Melanie, typed up his often indecipherable handwriting. Soon he was back in his office, sitting at his desk, writing out his life story on legal pads. On some days he’d stay at the office writing for hours after Melanie and I had left him.

His powers of concentration were extraordinary. I became accustomed to sitting silently in his office, waiting as he finished absorbing whatever he was reading. He brought that focus to anything he decided was worth his time. A devoted home cook, he studied the New York Times’s weekly food section so carefully that at least twice he showed me minor errors he’d found in the recipes.

He loved words and pulled out his dictionary or thesaurus during several of our discussions. (He wrestled in particular over which adjective best described James Baker, settling on “wily.”) Transcripts of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings he chaired from 1979 to 1987 show the careful deliberations he conducted over how to convey the committee’s meaning to the markets.

So of course he was a great letter writer. At his alma mater, Princeton University, I spent a few days reading through the papers he had donated, including copies of letters he’d written to important people like Milton Friedman, Alan Greenspan, Henry Kissinger. But also the four-paragraph response to a schoolgirl in Wyoming who asked which novel most influenced him (he named three: George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “1984” as well as “Oliver Wiswell” by Kenneth Roberts) and the thank-you letters to each Federal Reserve typist who worked overtime preparing materials for the Fed’s momentous announcement of a new approach on inflation in October 1979, one that focused on limiting the supply of money rather than on setting its price.

The aloof, scornful, fearsome character that was often portrayed by cartoonists during and after his tenure as Fed chairman probably helped him in winning the respect and trust of global policymakers and financial markets. His influence became so great that it was sometimes said that the dollar had moved off the gold standard and on to the Volcker standard.

But at root, Paul was a public servant -- someone who truly believed in the honor of serving others. His scorn was reserved solely for those who corrupted institutions or put their own selfish interests above the good of society.

To contact the reporter on this story: Christine Harper in New York at charper@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Anne Reifenberg

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.