The Stock Market Feeds the Racial Inequality It’s Free to Ignore

Do investors not care about what’s going on in the streets?

(Bloomberg) -- Over the past few weeks, as outraged crowds marched through the streets of America to demand an end to systemic racism, the country’s stock investors were busy bidding up the market at a dizzying clip.

At its height, with curfews enacted and videos of protesters clashing with police all over social media and President Donald Trump threatening to send in troops, the froth in markets became so extreme that, when observed on a three-month basis, every single company in the S&P 500 had swung into positive territory. It was a breathtaking display of indiscriminate buoyancy with no precedent in recent times.

Now, a rally at this precise moment in time may make perfect sense to market veterans steeped in the arcane ways of Wall Street, but for the uninitiated who are observing the mania from afar, it came off as more than a little jarring. Do investors not care about what’s going on in the streets? Do they think none of this will ever affect them?

Next to any answer to that question is a harsh truth -- that stock investing, with the power of compounding wealth that it spits out over the years, is dominated by the affluent, and in America that overwhelmingly means White people. Not only does this divide foster the inequality that serves as a root cause of the uprisings, but it also makes it easier for the investor class to ignore the tumult caused by the killing of George Floyd.

“A market is not a democracy, reflecting worldly concerns about inequality or race. It is a dollar-weighted counting machine, where investors’ views are weighted by how much money they have to invest,” said Aswath Damodaran, a professor of finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University. “A divergence between public and market views can be driven by wealth inequality, and to the extent that wealth and race are correlated, it will look unfair on a racial basis.”

Past episodes of racial unrest in the U.S. were treated with eerily similar investor indifference. Watts in 1965; Rodney King in 1992; the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, six years ago. Harrowing as they were, they were just exogenous dramas in markets –- as immaterial as, say, the outcome of that year’s Super Bowl -- that failed to dent investors’ conviction that the future flow of corporate earnings and politicians’ approach to public policy and taxation would remain, by and large, intact. And they have consistently been proved right.

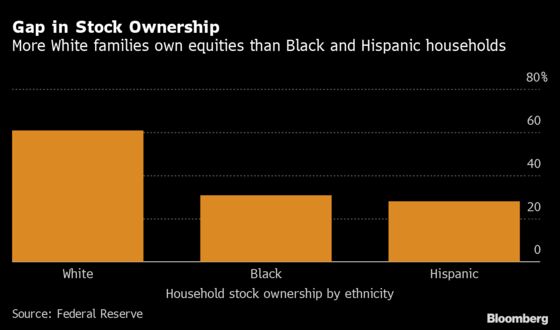

Lopsided ownership demographics are as big a fact of American markets as discrepancies in household income among races -- and each exacerbates the other. In the U.S., Black and Hispanic households own equities at about half the rate of White ones, according to Federal Reserve data. Research published by central bank staff shows trends in asset ownership have furthered wealth inequality, while analysis by the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute indicates disparate holdings have helped to inflate the already substantial racial wealth gap.

Data from the Fed shows about 52% of families held stock positions in 2016, while Gallup polls this year put the number at 55% of Americans. Breaking it down by racial makeup, 31% of Black households and 28% of Hispanic ones own equities either directly or indirectly, according to analysis published by the central bank. That compares with 61% of White families.

“We don’t have multi-generational wealth,” said John W. Rogers Jr., founder of Ariel Investments, one of the biggest Black-owned investment firms. “And so therefore, we don’t have grandfathers and grandmothers and aunts and uncles that have been teaching us about the markets as we grow up, and how to get comfortable in the wealth that can be created in the stock market.”

Disparities like these, mirroring gaps in income, allow divisions in wealth creation to expand, particularly in the post-crisis period, where over the last decade the S&P 500 has delivered annualized returns of almost 17% and some $25 trillion of value was added to the value of American stocks. Indeed, at times during the bull market, gains in U.S. shares exceeded gains in worker pay by more than any stretch in at least half a century.

The picture of inequality has been in especially stark relief in 2020, a year in which job losses caused by the coronavirus lockdown are falling disproportionately on American minorities while the stock market -- down more than 30% in March -- clawed back most of its losses. While optimism over reopening explains some of the exuberance, as big a factor was the Fed, whose frantic campaign to backstop markets has been manna for the investing set.

Against that backdrop, Raphael Bostic, the first Black Fed president in the central bank’s 106-year history, called on policy makers to take action to create more opportunities for minorities and the poor. In an interview with Bloomberg News, Bostic said he’s looking at a proposal for the Fed to target Black unemployment, which was still rising last month even as the overall rate began to decline from its lockdown peak.

A paper authored by Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick and Ulrike I. Steins and accepted for publication this year by the Journal of Political Economy indicates that after the Great Recession, the bottom 50% of Americans in terms of wealth distribution saw that wealth shrink by 15% of its 2007 level by 2016, primarily due to the drop in residential real estate value. The top 10% emerged relatively unscathed thanks to equity gains, and were the primary beneficiaries of that performance.

Meanwhile, there was an outsize negative impact on Black Americans.

“The financial crisis has hit Black households particularly hard and has undone the little progress that had been made in reducing the racial wealth gap during the 2000s,” the paper said. “The overall summary is bleak. The typical Black household remains poorer than 80% of White households.”

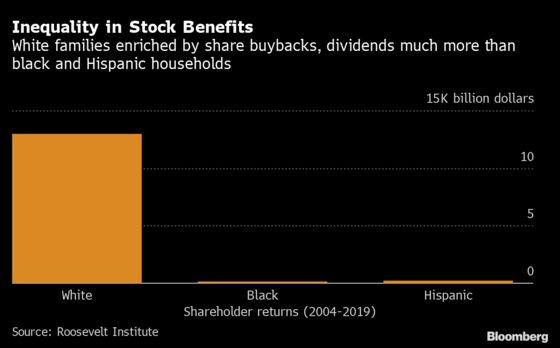

A working paper published this year by the Roosevelt Institute authored by Lenore Palladino, a fellow at the think tank and an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, found that the unequal distribution of stock ownership has played an increasing role in amplifying the racial wealth gap.

According to her analysis, shareholder payments in the form of stock buybacks and dividends that went to White families between 2004 and 2019 totaled $13 trillion, compared with $181 billion that went to Black households and $212 billion that went to Hispanic households in the same period.

“In the last decade we talked about the ‘one percent’ as a wealth group in society,” but the conversation often didn’t clarify the group consisted of wealthy White households, Palladino said in a phone interview. “And that’s a really important indicator of what’s going on in American politics today.”

According to Ariel’s Rogers, that sort of racial inequality in terms of economic opportunity can eventually reach a boiling point.

“All the problems that face our society all come back to the fact that we’re a capitalist democracy,” he said. “And if we’re not fully participants in the capitalist democracy, it just compounds and compounds and compounds and creates the kind of frustration that you’re seeing in the streets.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.