The Poker Aces Playing a Key Hand in the $5 Trillion ETF Market

The Poker Aces Playing a Key Hand in the $5 Trillion ETF Market

(Bloomberg Markets) -- On City Avenue in the Philadelphia suburb of Bala Cynwyd, Pa., across the street from a TGI Fridays and California Pizza Kitchen, sits a bland building that looks like any other corporate office. The only notable feature is in the parking lot: a large oak labeled a “significant tree” because it survived the American Revolution.

And yet within that dull gray-brown edifice, away from the trading hubs of New York and Chicago, sits a crucial engine of the $5 trillion global exchange-traded fund market, one increasingly relied upon by investors ranging from hedge funds to individuals. What’s more, the little-known billionaires behind the operation have groomed a generation of canny market experts.

Like its headquarters, Susquehanna International Group LLP is hidden in plain sight. It keeps a low profile even though its fingerprints are everywhere in financial markets. In addition to ranking among the largest U.S. traders of ETFs, it’s a giant in options trading and has plowed into sports betting, private equity, and even Bitcoin.

Susquehanna, as well as other under-the-radar, closely held competitors created by its alumni, such as Jane Street Group LLC, grease the wheels of the ETF market, keeping the instruments inexpensive and easy to trade. As better-known Wall Street companies such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc. have stepped back from performing this function in recent years, regulators have started asking more questions about the stability of the market, which has become dependent on Susquehanna and its brethren.

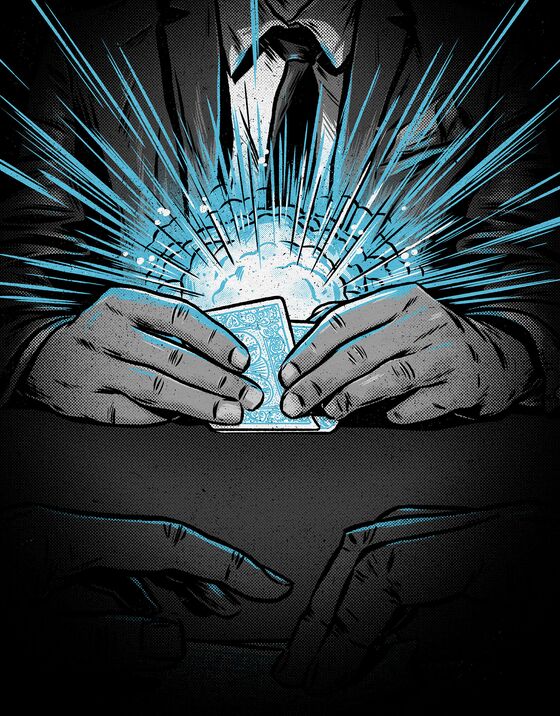

Susquehanna built its empire on poker. All six co-founders met in the late 1970s at the State University of New York at Binghamton, where they gathered to play cards before advancing to Las Vegas casinos. One of the six, Jeff Yass, had the insight that card skills could transfer to Wall Street. That bloomed into Susquehanna’s philosophy that poker provides the best training for the type of probability-based decisions in uncertain circumstances that are needed in markets.

Yass proved to be a preternatural trading talent. He was in his 20s when Izzy Englander, now chief executive officer and founder of Millennium Management, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, sponsored him for a seat on the floor of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange.

Yass persuaded his five college buddies to join him in Philadelphia. With Steve Bloom, Eric Brooks, Arthur Dantchik, Andrew Frost, and Joel Greenberg, he founded a firm in May 1987 to deploy their poker skills in the options markets. They named it after the 444-mile river that runs from near their alma mater in upstate New York through Pennsylvania, the home of their new venture.

“My friends and I took poker very seriously,” Yass said in an interview in the book The New Market Wizards: Conversations With America’s Top Traders by Jack Schwager, published in 1992. “We knew that over the long run it wasn’t a game of luck, but rather a game of enormous skill and complexity. We took a mathematical approach.”

Neither Yass nor his co-founders would comment for this story, according to Dave Pollard, Susquehanna’s head of strategic planning and special counsel. The following account is based on interviews with current and former employees and people familiar with the firm.

Five months after Susquehanna was founded, the U.S. stock market crashed, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average suffering its largest ever one-day percentage decline. Susquehanna not only survived, but thrived. By October 1988 the firm had 100 employees, and it had brought in about $30 million in its first year, compared with $43 million earned by PaineWebber & Co., which had about 12,900 employees, according to a Washington Post story at the time.

Today, including those who work at its Pennsylvania headquarters, Susquehanna has about 2,000 employees in six other offices in the U.S., five in the Asia-Pacific region, and two in Europe. Options and ETF trading are the pillars of its business. It trades about 7 percent of U.S. ETF volume and more than $1.5 trillion in ETFs globally on an annual basis, according to a person familiar with the firm’s trading activity. In U.S.-listed options, Susquehanna handles about a quarter of total trades, the person said.

By all accounts, Yass is a workaholic. Legend has it that he’s been seen in a robe and slippers heading into the office to put on a trade. In contrast to hedge fund stars such as Citadel’s Ken Griffin or Bridgewater Associates’ Ray Dalio, the balding, bespectacled Yass isn’t widely recognized. He can be seen around the office in sneakers and jeans. He stays out of the headlines, other than occasional appearances among top donors to political candidates, especially those with a libertarian bent.

Susquehanna’s recruits, the majority of them straight from undergraduate programs, undergo rigorous training at poker tables, where they receive feedback on their strategy. Employees learn a specific approach to risk-taking. Traders who make losing bets for the right reasons are favored over those who get lucky betting against the odds.

The firm’s website touts its “entrepreneurial mindset,” gamer blog, and day-in-the-life portraits of a software developer and a quantitative researcher—more like a tech startup than a financial giant. Its Facebook page chronicles outings to baseball games and its no-limit Texas Hold ’em annual poker tournament.

“The basic concept that applies to both poker and option trading is that the primary object is not winning the most hands, but rather maximizing your gains,” Yass told Schwager in The New Market Wizards.

More than three decades ago, Susquehanna’s game-theory experts discovered they had an advantage in a rapidly expanding market. Options contracts give an owner the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a security at an agreed-upon price within a set time frame. Their popularity exploded in the 1970s and ’80s after a new model for pricing options was formulated, making them easier to trade.

Yass and his colleagues were quicker than old-school stock traders to understand the math behind these models, especially as increasingly complex products, such as options on an entire index, emerged.

In the early 1990s, a new instrument arrived: the ETF. The product offered exposure to the entire basket of securities in an index, similar to an index mutual fund, but traded on an exchange like a single security.

For traders with options expertise, particularly in so-called index options, testing out ETFs was a natural leap. Part of the product’s appeal was the flexibility it offered for hedging, arbitrage, and portfolio diversification.

An entire asset class bloomed from the original U.S.-listed ETF, State Street Corp.’s SPY, based on the S&P 500 index. Susquehanna had a front-row seat as one of the independent options brokers to take an early interest in trading the instruments and the securities that underlie them.

“If you aren’t an expert on option theory, it’s very difficult to be an expert in decision-making. So it’s very difficult to be competitive in anything where you have to make decisions,” Yass explained at a 2008 roundtable discussion celebrating the Chicago Board Options Exchange, according to a Wall Street Journal transcript of the event.

The niche began to attract bigger players in the early 2000s, with Goldman Sachs and Bear Stearns Cos. among the buyers of independent specialists. But the regulatory crackdown following the 2008 financial crisis curbed U.S. banks’ proprietary trading. Big Wall Street companies shrank from low-margin activities that required a lot of capital and technology investment. Independent companies such as Virtu Financial Inc. and Citadel Securities—two of the largest traders of U.S. equities—became dominant market intermediaries.

Susquehanna succeeded in making the transition to a technology-driven world as a veteran privately held, independent trader. Unlike other big market makers, it doesn’t rely on high-speed strategies. It specializes in ETF products that are more difficult to trade, according to people familiar with the firm. Each day it handles about $1 billion in creations and redemptions, the terms used to describe the process of bringing new shares of an ETF to market or trading them in for the underlying securities. Susquehanna trades about 100 million ETF shares per day.

The firm and its competitors seek profits in market anomalies, such as discrepancies between an ETF’s price and the value of its underlying components. As proprietary traders, Susquehanna employees deploy the firm’s own capital, enhanced with borrowed money, or leverage.

“These guys don’t make any money from increased exposure,” Phil Bak, CEO of Exponential ETFs, an issuer of ETFs, says of Susquehanna and its fellow market makers. “If they find an arbitrage opportunity, even if it’s a fraction of a penny, their job is to maintain that edge as much as they can.”

Yass and his co-founders have kept tight control of the firm, frustrating some employees who want an ownership stake or more influence. Susquehanna has sought to prevent defections with noncompete clauses and lawsuits.

Alumni have risen to the top elsewhere. Reggie Browne, a senior managing director at Cantor Fitzgerald & Co. who’s sometimes called the “godfather of ETFs,” spent eight years at Susquehanna. (Global Trading Systems LLC, one of the biggest U.S. stock traders, agreed to buy Cantor’s ETF unit in November.) Chris Hempstead worked at Susquehanna for more than nine years before helping to build the ETF business at KCG Holdings Inc. Virtu bought KCG in 2017.

Perhaps the most prominent group of defectors went on to start one of Susquehanna’s most successful rivals in 2000. New York-based Jane Street’s founders included former Susquehanna employees Tim Reynolds, Rob Granieri, and Michael Jenkins. It trades an average $13 billion in global equities every day and handles 7 percent of ETF volume worldwide, according to its website.

Jane Street has an ethos similar to Susquehanna, including an emphasis on undergraduate recruitment and puzzles. Its office displays an Enigma encryption machine used in World War II; the company’s logo even makes a subtle reference to an Enigma rotor.

Jane Street’s quantitative and algorithmic trading helps make markets more efficient, Matt Berger, global head of fixed income and commodities, said in an emailed statement. “Game theory is relevant at times but not the primary lens through which we view trading,” he said. “In contrast to how many people think about game theory, we focus on positive-sum interactions.”

Co-founder Reynolds, who was paralyzed in a car crash the year the firm was founded and uses a wheelchair, left Jane Street in 2012 to focus on philanthropy. Among other things, he funds programs that teach photorealistic painting to underprivileged students. The firm has no CEO and is managed by a group of partners. Reynolds, Granieri, and Jenkins wouldn’t comment for this story.

Regulators have started taking a greater interest in the role that firms such as Susquehanna play in the market. Concerned about volatility and a lack of transparency in the ETF market, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission approved a rule in 2016 that requires ETF issuers to disclose which firms they use to smooth trading in their products.

The growth in ETF market makers hasn’t kept up with the growth in ETF assets or trading volumes, according to James Simpson, former associate director of the American Stock Exchange’s ETF Marketplace and now president of ETP Resources LLC, a data and consulting firm specializing in ETFs. Unlike publicly traded firms, Susquehanna doesn’t disclose how much money it has to absorb losses and maintain orderly markets.

Regulators and market participants are concerned about how much capital these firms could put up in a stressful situation, Simpson says. Retail investors, attracted to ETFs because they’re easy to trade, may not realize how quickly that advantage could change, said Peter Kraus, former CEO of AllianceBernstein, in a September interview with Bloomberg’s Trillions podcast. “The liquidity of the ETF itself relies on market participants who actually trade them,” said Kraus, who now runs Aperture Investors LLC, an asset manager. “I don’t think investors actually understand that risk.” The Financial Stability Oversight Council, a government body charged with identifying and responding to threats to the financial system, has raised a similar concern, saying the ETF arbitrage mechanism is vulnerable to breakdowns in severe market stress.

If Susquehanna’s leaders are concerned, they haven’t shown it. Instead, they’re placing bets on new markets. The firm got involved in cryptocurrencies in 2014 when Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss sought help on a Bitcoin ETF they proposed to regulators, which hadn’t gained approval as of early November. Meanwhile, Susquehanna trades millions of dollars of cryptocurrencies, an asset some mainstream firms have deemed too risky.

And, as you might expect from a group of seasoned gamblers, sports betting fascinates Susquehanna’s co-founders. Its Dublin-based unit, Nellie Analytics Ltd., wagers on sports such as soccer, tennis, basketball, and football. In May the U.S. Supreme Court ended a federal ban on sports betting outside of Nevada, and Susquehanna has been posting job openings for sports traders at the Bala Cynwyd office. That could deal Yass and his firm yet another winning hand. —With Rachel Evans

Massa is a reporter on Bloomberg’s investing team in New York.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christine Harper at charper@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.