The Poison Pill, Long Hated by Investors, Gets New Love in Japan

The Poison Pill, Long Hated by Investors, Gets New Love in Japan

(Bloomberg) -- One of the corporate world’s most controversial takeover defenses is winning some unexpected fans.

The poison pill -- which dilutes the ownership of hostile acquirers -- has long been criticized as a tool to keep bad management teams in place and deny existing shareholders the right to profit from buyouts. But a takeover battle in Japan is now spurring endorsements for the tactic by corporate governance experts and influential proxy advisers, and even making some activist investors consider giving it support.

Tokyo-based Shinsei Bank Ltd. has asked shareholders to approve on Thursday its plan to use a poison pill defense against a proposed stake increase by SBI Holdings Inc. The argument in favor of Shinsei’s plan: It’s the best strategy to extract better terms for existing investors.

“Poison pills generally are not terribly good for shareholders,” said Jamie Rosenwald, a co-founder and portfolio manager at Dalton Investments, a $3.4 billion U.S. money manager that owns about 3% of Shinsei for clients. But if the aim is to secure a better deal for investors, that would be a “reasonable reason,” he said.

The defense measure’s chances of passing in Thursday’s vote were dealt a blow when people familiar with the matter said that Japan’s government -- which owns more than a fifth of Shinsei’s shares -- is poised not to support the proposal. Even still, the case shows how takeover defenses are evolving as companies become more sophisticated about the strategies.

SBI, led by a maverick financier named Yoshitaka Kitao, launched a rare unsolicited tender offer in September to increase its stake in Shinsei to about 48%, a level that would give it effective control of the lender without having to go through additional regulatory hurdles.

Shinsei said it would support the bid on two conditions: that SBI raise its offer and scrap a ceiling on the number of shares it will buy, so that all holders could tender. SBI refused to pay even one-hundredth of a yen more. Shinsei moved forward with the poison pill proposal.

Perhaps surprisingly, Institutional Shareholder Services Inc., the influential proxy adviser, said it was backing the defense plan, arguing it was being used to help shareholders. Shinsei “appears to try to leverage the pill as a tool of negotiation with SBI Holdings to extract better terms,” ISS wrote in its Nov. 7 report.

ISS also criticized the partial offer, which it said will disadvantage minority shareholders who are unable to tender their stock. It noted that the pill was intended only for SBI and would expire next year.

“There are two types of poison pill, those in place all the time and those introduced as one-time measures,” said Takeyuki Ishida, head of Japanese research at ISS in Tokyo. “In recent years, ISS has recommended voting against almost all of the first kind. For the second kind, we’ve seen about five or six of them in that time, and we decide on a case-by-case basis.”

Glass Lewis & Co., the other major proxy adviser, also supported the Shinsei pill, pointing to SBI’s partial offer as its chief reason.

“This is not a typical ‘Just say no’ takeover defense situation,” said Nicholas Benes, who heads the Board Director Training Institute of Japan.

“This may be one of the only cases in Japan’s history where a poison pill was used for the purpose that poison pills were designed for: to enable the target company to get negotiating power and time so as to get a higher price for all shareholders,” he said.

Even activist investors who seek to profit from such bids haven’t ruled out voting for Shinsei’s plan. Dalton, which has long waged campaigns at Shinsei, said in an interview this month that it was still debating it internally. Hong Kong-based hedge fund Oasis Management Co. said the bank’s directors would have to come up with “substantial value-creating actions” to get its support.

The poison pill was invented in 1982 by New York lawyer Martin Lipton, one of the founders of law firm Wachtell Lipton Rosen & Katz. It enabled boards of directors to level the playing field against the corporate raiders of the time, financiers who were in the habit of making hostile takeover bids.

A key moment in the takeover defense’s history in Japan was the contentious battle for Bull-Dog Sauce Co. in the 2000s. The Supreme Court in 2007 refused to block a poison pill instituted by the condiments maker against Steel Partners, an overseas activist investor that became well-known in Japanese business circles. The case led to criticism that Japan was closing ranks to keep out foreign investors.

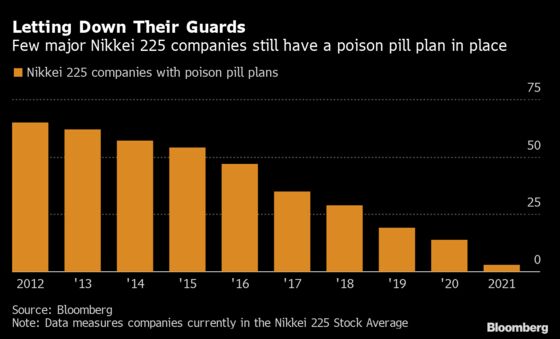

Japanese firms rushed to add poison-pill defences in the late 2000s following the Bull-Dog decision. Those moves came as Steel Partners and other foreign activists were seen as corporate raiders with little interest in Japan or its companies. The high-profile arrests of controversial entrepreneur Takafumi Horie and homegrown activist investor Yoshiaki Murakami also worsened perceptions of hostile takeovers and shareholder activism.

The tide turned for the defense measures after the corporate governance overhaul instituted by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe starting in 2014. Japan’s new rules for companies, introduced the following year, frowned on takeover defense measures, saying they “must not have any objective associated with entrenchment of the management or the board.” Throughout Abe’s term, many companies scrapped such defense plans.

But over the past couple of years, there have been some high-profile cases where poison pills, particularly one-time defenses, won investor and court support. Shibaura Machine Co., then known as Toshiba Machine Co., successfully used the measure to thwart a takeover bid by Murakami last year. ISS also supported that plan.

Just last week, the Supreme Court dismissed an effort to block Tokyo Kikai Seisakusho Ltd.’s poison pill. The maker of printing presses had excluded its prospective acquirer, which held 40% of its shares, from a shareholder vote on introducing the measure. The decision may be an important precedent for takeover defenses in Japan.

Attention now turns to how enthusiastic Japan’s new prime minister, Fumio Kishida, will be about Abe’s shareholder-friendly corporate governance overhaul. He has different views about capitalism, saying that some of the country’s reforms have widened the gap between rich and poor.

So it’s perhaps fitting that, in the case of Shinsei and SBI, the government may ultimately decide the poison pill vote.

It’s the largest shareholder of Shinsei in return for a bailout it gave the lender in 1998. It holds the shares through two affiliated bodies, Deposit Insurance Corp. of Japan and one of its units.

The government plans to either vote against the poison pill or cast a blank vote, people familiar with the matter said, asking not to be identified discussing private information. Calls to DICJ and Shinsei went unanswered Tuesday, a public holiday in Japan.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.