The New Hedge Fund Manager Flies Economy and Stays in Hostels

The New Hedge Fund Manager Flies Coach and Stays in Hostels

(Bloomberg) -- Brant Rubin started a hedge fund last year only to find it wasn’t the easy path to riches it used to be.

He’d quit his job buying into European internet companies for London’s Luxor Capital in 2017 to set up his own shop and raised almost $50 million from family, friends and a couple of former clients. Then, reality struck. The fundraising didn’t cover his overhead and his corner of the market was falling out of favor with the forces he had to answer to: potential customers and European financial watchdogs imposing onerous new rules.

“It’s not as lucrative anymore,” said Rubin, 39, who’s had little luck raising additional capital from the more than 100 investors he’s approached because they tend to avoid startups. “Burning money is uncomfortable, particularly as we don’t have unlimited money to burn. But I believe in our business.”

So Rubin and like-minded financiers are following the same rules that entrepreneurs the world over routinely follow: they’re tightening their belts. In the case of the Columbia Business School graduate, he avoids $500-a-night hotels in favor of hostels when traveling to court potential clients. He flies budget airlines like Norwegian Air and opts for subways instead of Uber.

He and his two colleagues at Vor Capital have an office above a casual steakhouse in Covent Garden, a more bustling, tourist-heavy area of London than the posh Mayfair district favored by older, established hands.

Rising costs and shrinking returns have blown up the calculus for hedge fund startups, mainly by driving up the amount of assets funds need to break even. Whereas a few years ago it was possible to cover bills with the fees earned on $50 million under management, now many require at least $200 million, according to Simmons & Simmons, a law firm representing three quarters of the U.K.’s largest hedge funds and half of America’s biggest managers.

Getting there is a lot harder, too: The average startup size for new funds tumbled 72 percent to $28 million since 2000, according to Singapore-based data provider Eurekahedge.

“Investors flock to two or three large launches every year, leaving the rest to slog through managing modest assets, waiting to either prove themselves or praying for a better asset-raising environment,” said Vaqar Zuberi, head of hedge funds at Geneva-based Mirabaud Asset Management, which oversees 9 billion Swiss francs ($9.03 billion).

Large institutional investors like pension funds and insurers generally won’t even look at a hedge fund until it has a three-year track record of returns and manages more than $100 million.

In the interim, entrepreneurs are finding a lot can go wrong. It took less than two years for Stephen Hull and Kevin Connors to shut down their London-based hedge fund, Ibex Capital, after losing a big client this month, according to a letter to investors seen by Bloomberg. That happened even though the seasoned duo’s resumes include stints at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Moore Capital Management and Brevan Howard Asset Management. Connors declined to comment when reached by e-mail.

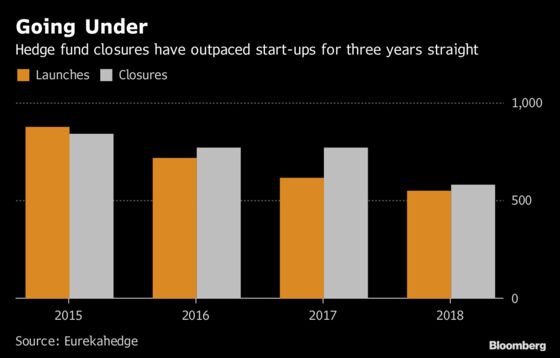

The headwinds for new funds are adding to pressures in a part of the industry already in retreat. In the past three years, more hedge funds have closed than opened, including 580 going out of business globally last year, versus 552 launches, Eurkeahedge data show. Compare that with the heyday of the 2000s when it was common to have more than 1,000 annual startups, and it’s clear that years of dismal hedge fund performance have undermined the entrepreneurial spirit.

With hedge fund returns sometimes lagging even the lowest-cost index funds, people are less willing to reward even established managers with the 2 percent management fees and 20 percent performance fees that used to be the industry norm. Those figures fell to 1.43 percent and 16.93 percent, on average, last year, data from Hedge Fund Research show. Even so, outflows from hedge funds have reached almost $100 billion since the start of 2016, according to eVestment.

But there’s always someone who believes they’re building a better mouse trap. Hedge funds can be more aggressive than traditional mutual funds—for instance, they can bet stocks will fall—and many new managers are convinced they have something unique to offer. They just have to tweak the business model.

Take Jeff Henriksen, part of a three-person team setting up Thorpe Abbotts Capital in Virginia. It’s based near University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, ranked among the 10 best business schools by Bloomberg Businessweek. The trio are in early talks with Darden to hire students instead of more seasoned analysts to do research, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

“We pay the interns, but not as much as we’d have to pay to hire analysts,” he said. “You have to be creative.”

To get around tough fundraising conditions, former Bridgewater Associates executive Alexander Campbell developed a technology that aggregates economic indicators, which he’s selling to get closer to his $100 million start-up target for Black Snow Capital.

Others are bypassing the tradition of opening up shop in prestige neighborhoods to be down the street from some of the industry’s best-known players like Millennium Management, which oversees $35 billion, or Rokos Capital Management, managing about $8.2 billion.

Both have London offices in Mayfair, the area sandwiched between Oxford and Regent Streets, Piccadilly and Hyde Park, where renting office space for six people typically costs about 150,000 pounds ($195,000) annually, according to Dale Gabbert, a partner at Simmons & Simmons. That falls up to 30 percent if you set up shop in areas like Soho or Covent Garden and by more than half in the city of Oxford.

“If you’re good at managing money, you don’t have to be in a super swanky office in Mayfair,” said Gabbert, adding that of the 15 start-up hedge fund clients the firm worked with last year in London, only four have offices there. “There is a clannish aspect to the industry and people want to be seen. But at the end of the day, institutional investors don’t care where you are.”

In Europe, opting for downmarket office space is becoming more of a necessity than a choice after last year’s so-called MiFID II banking regulations forced funds to pay for research that used to be free and install expensive software to, for one, report equity trades by the minute. Hiring a compliance officer can cost 100,000 to 150,000 pounds annually.

Irene Perdomo is making it work. She started Devet Capital four years ago with just $750,000 out of a spare room in a house in Wimbledon, the London neighborhood known for its tennis tournaments. Now the former Barclays and Noble Group commodity trader and her partner, ex-GLG Partners portfolio manager Leonardo Marroni, are managing over $100 million from the same space. They either go and meet clients where they are, or invite them over.

“There’s a lot of biased information about people trying to sell you things, and a lot of it you really don’t need when you’re starting out,” she said.

For Rubin, who made a 10 percent return last year by putting money in niche European internet firms, the forced frugality does have its advantages. One of his trading convictions is Dublin-based Hostelworld Group Plc, a small business similar to Booking.com or Expedia.com. He books his own accommodation at hostels like Generator Stockholm, which has more than 2,700 reviews on the site.

“We’re trying to get a better understanding of the business and the hostel traveler, which ties in nicely with our limited budget,” Rubin said. “We’re killing two birds with one stone: Doing research and saving money.”

--With assistance from Melissa Karsh and Mark Burton.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sree Vidya Bhaktavatsalam at sbhaktavatsa@bloomberg.net, Daliah MerzabanChitra Somayaji

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.