The Market Knew About the Press Release Hackers Before the Cops

The Market Knew About the Press Release Hackers Before the Cops

(Bloomberg) -- Can stock traders tell when something fishy is going on in the market? Researchers who studied scandals in which hackers used inside information to profit from earnings announcements say: yes.

To see how sensitive markets are to hidden influences, three professors set out to measure how quickly traders picked up on the activity of crooks who used stolen data to front-run earnings releases in about 800 companies. Very quickly, was their conclusion, published in an April 3 paper, “Retail Insider Trading and Market Price Efficiency: Evidence from Hacked Earnings News.”

Being professors, the authors were less interested in crime and punishment than whether the market is efficient enough to sense when something unusual is happening -- namely, that someone with inside information has started to buy. They were seeking to test academic theories that say retail investors like the hackers don’t have enough juice to sway stocks.

“It is surprising to us that a group of potentially 100 smaller, relatively sophisticated but certainly not institutional investors, were able to move prices, ” said University of Toronto professor Pat Akey, who wrote the paper along with colleague Charles Martineau and Vincent Gregoire of HEC Montreal. “That a smaller group of hackers was able to have a distinguishable and large-in-magnitude effect, we think, is quite novel.”

The background: from 2010 to 2015, criminals breached newswire servers to access earnings announcements before they were published. They used brokerage accounts to trade off the information -- taking long and short positions, using options and other derivatives -- hours before it was released. They also sold the data to other individuals on the black market, all in all booking profits of more than $100 million. Many of them are going to prison.

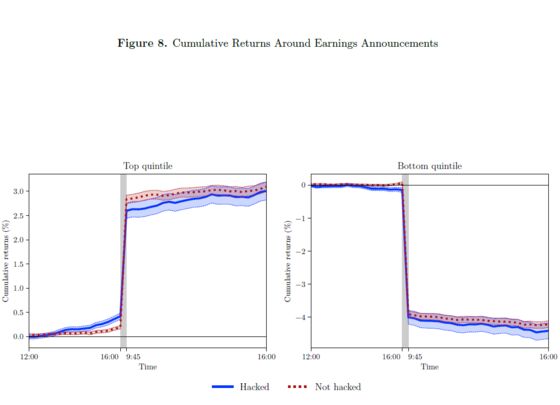

Among the researchers’ findings was that in the hours before earnings were officially released, the direction of prices in hacked stocks was nearly twice as likely to predict whether the company missed or beat estimates than it usually is.

Criminals trade on stolen data and are able to sway a price -- so what? But for researchers peering deeply into the market’s electronic’s innards, the episode was a laboratory to examine a question that has occurred to anyone who has watched a single fat-finger trade ignite a volume frenzy in which hundreds of thousands more shares change hands. How much trading does it take to convince others something is going on?

Through a certain lens, the entire stock market can be viewed as a system for identifying investors who know more than everyone else. High-frequency computers prowl orders trying to suss out real buyers and sellers from the day’s usual back-and-forth flotsam, looking for orders that might permanently change a stock’s price. The authors found it doesn’t take a whole lot to get their attention.

“In classical microstructure models, trades from retail traders (or noise traders) do not impact the fundamental value of the stock,” the authors wrote. This time, however, they did. “Most of the traders involved in this illegal trading scheme were retail traders who were members of the hacker’s extended families or of their social circle. They frequently traded using their personal brokerage account.”

To test whether or not stocks can suss out informed trading, the authors compared a group of firms that the hackers had early earnings access to -- determined by publicly available court documents -- to companies that were not breached. Besides measuring the accuracy of the pre-release drift, the researchers tested to see if hacked stocks moved less once the earnings results officially came out. They did: post-release moves were about 15 percent smaller when the information had been stolen.

“We are not able to say with certainty that markets observed this as insider trading,” Akey said in an interview. “What we can say is it’s likely that they recognized there was a large uptick in abnormal volume, and they may have believed that somebody was trading off of information they didn’t have.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.