The Man Who Inherited Australia's Downturn Just Isn't That Fazed

The Man Who Inherited Australia's Downturn Just Isn't That Fazed

(Bloomberg) -- Josh Frydenberg mulled a tennis career before going on to study economics and law, earn degrees from Oxford and Harvard Universities, and vault up the ranks of the Liberal Party. His latest challenge: to graduate from retail politics to top economic official charged with arresting a downturn.

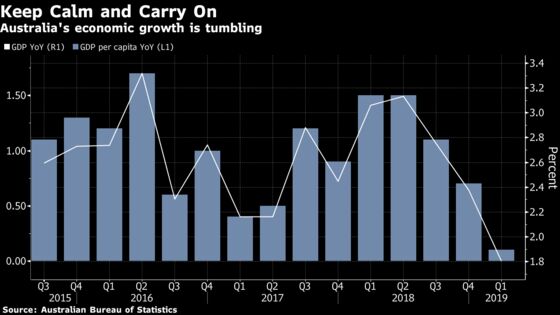

Since the 47-year old was sworn in as Treasurer last August, annualized economic growth has slumped to a meager 1.2% from almost 4%; the employment outlook has worsened with advertisements falling in eight of 10 months; and property prices tumbled even faster -- prompting households to slash spending.

That’s all put the economy on track for its weakest fiscal year since the last recession in 1991. Even the Reserve Bank, which rarely wades into political territory, is urging more government stimulus after cutting interest rates for the first time in almost three years.

But whether boxed in by his sunny disposition or pledges to deliver a budget surplus made ahead of the government’s shock re-election last month, Frydenberg appears unfazed. While he’ll push to pass tax cuts when parliament resumes on July 2 and ramp up infrastructure spending, that’s about it, leaving the heavy lifting of stimulus to the central bank.

“I’ve found the treasurer to be remarkably sanguine,” said Danielle Wood, an economist at the Grattan Institute, an independent think tank in Melbourne. “When you’ve got the central bank governor coming out and talking about perhaps moving to stimulatory fiscal policy as well as the need for more long-term structural reforms, I’d be hoping for a more substantive response.”

When the RBA reduced the cash rate to a record-low 1.25% two weeks ago, Governor Philip Lowe warned against over-reliance on monetary policy, arguing there were better options to revive growth and reduce unemployment. He said his preferred strategy was structural reform that fostered “a strong, dynamic business sector” to lift productivity and, in turn, raise living standards.

Following Lowe’s speech and signal that the RBA will likely ease further, Frydenberg was asked repeatedly for his reaction. The treasurer responded as he had during the election campaign, outlining the government’s plan of A$158 billion ($108 billion) in tax cuts, A$100 billion of infrastructure spending and incentives for small and medium-sized firms to invest.

But don’t expect a sugar hit. The vast majority of the tax cuts won’t hit until the middle of next decade, and the investment is over 10 years, diminishing its impact. At the same time, the government is winding back tax incentives for research and development that could uncover new growth drivers.

Frydenberg said Tuesday that the government would introduce its tax package in the first week of parliament.

In minutes of its June policy meeting a few hours later, the RBA said another rate cut “was more likely than not” given the amount of spare capacity in the jobs market and the economy. It also reiterated that lower rates “were not the only policy option available to assist in” reducing unemployment, in a thinly-veiled reference to potential government measures.

Accidental Treasurer

Since the Reserve Bank’s rate cut, Frydenberg’s Twitter feed has largely comprised smiling snapshots with a who’s who of global finance in trips to London and G-20 meetings in Tokyo.

Becoming treasurer almost by default in last August’s leadership upheaval that saw Malcolm Turnbull ousted from power, Frydenberg inherited an economy on auto-pilot as immigration and commodity exports underpinned growth. Pre-election polls also signaled he wouldn’t last long enough to confront the economy’s underlying problems.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s shock victory suddenly meant the challenge of turning this all around fell squarely on Frydenberg’s shoulders.

In an interview with Bloomberg News at the Group of 20 finance meetings in Japan, Frydenberg again referenced his plan and highlighted that Australia is in its 28th year of expansion, describing this as “a remarkable run, a run that will continue.”

He’s probably right: immigration, Chinese commodity demand and government spending make it hard for GDP to decline for consecutive quarters -- the local definition of a recession. When measuring economic growth per person, however, the numbers tell a different story.

“The long-term challenge for the economy is that it faced a per-capita recession in the second half of 2018 meaning that growth was driven by population,” said Joanne Masters, chief economist at Ernst & Young LLP in Sydney. “With participation already high by historic standards, future growth and improved living standards require improved productivity performance.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Michael Heath in Sydney at mheath1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Chris Bourke, Malcolm Scott

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.