The Mindless, Money-Minting Brazil Trade Is Now Officially Dead

In its place, something has emerged that’s rarely been seen here: a willingness to take on risk to juice returns.

(Bloomberg) -- It is called the Brazil Kit. And for two decades, investors adhered to its simple maxim religiously: load up heavily on local government bonds, sprinkle in a few other assets and rake in the fattest and most facile of returns -- 10% a year, 15%, sometimes even 20% or more.

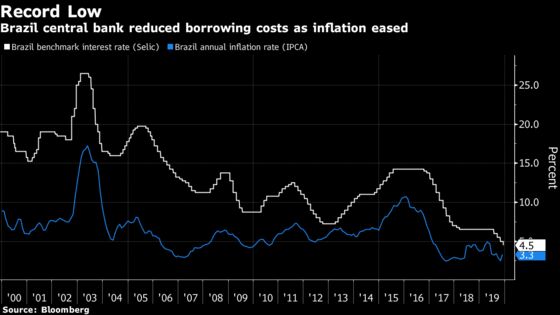

But today, after policy makers drove down the benchmark interest rate time and time again in recent years, to a mere percentage point above Brazil’s 3.3% inflation rate, the Kit is for all intents and purposes dead.

In its place, something has emerged that’s rarely been seen here: a willingness to take on risk to juice returns. Investors are suddenly poring through research reports and piling into hot stocks and dabbling in high-yield bonds. This sort of thing is nothing new across much of the world, of course, but in Brazil, it’s revolutionary.

So far, at least, it’s all working out great. Companies are selling unprecedented amounts of bonds to tap into the new demand. The stock market is hitting record highs on an almost daily basis. Brokerages are beefing up their equity-research staffs. And dozens of executives have departed top-tier financial firms in the past couple of years to start their own hedge funds, betting riches can be made guiding clients to more complex investments.

“It is a new world,” said Daniel Motta, the head of fixed income and equities trading at Goldman Sachs in Sao Paulo.

There are huge potential benefits for the sputtering Brazilian economy from this shift. By gaining access to the kind of financing they never had in the old Brazil Kit days, companies can more easily invest, expand and hire. There are dangers too. As Brazilians rush headlong into riskier financial products they know little about, some warn of the potential for a mania that could inflate asset prices, setting the groundwork for a sudden sell-off down the road that would burn the newbies.

“The growing number of individuals entering the Brazilian stock market is a risk, obviously,” said Fernando Siqueira, a portfolio manager at Infinity Asset Management. That risk, he said, is “somewhat” mitigated by the new research products that investors can tap.

Brazil’s benchmark interest rate, known as the Selic, is down to 4.5% after policy makers cut it for a fourth time this year on Dec. 11. For all the marvel at how low global rates are -- 0.25% in Israel, -0.5% in the euro area and -0.1% in Japan -- the Selic rate is arguably the most shocking of them all, the one that best epitomizes the new normal of easy money.

As recently as three years ago, it stood at over 14%. Go back a bit further and it clocked in above 20%, and further yet, to 1999, and it reached as high as 45%, a level that was some 40 percentage points above the going inflation rate.

There’s long been great theoretical debate about why Brazilian rates were so high, but an unmistakable component of it was the country’s hyper-inflationary past and the way that episode scarred investors. As those memories have faded, central bankers gained room to cut rates in a bid to shore up an economy that has been mired in near-zero growth for much of the past decade.

The impact of the rate declines has perhaps been most visible in the corporate bond market, where issuance surged from about 67 billion reais ($16.4 billion) back in 2016 to 165 billion reais so far this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Among the new faces borrowing for the first time is a struggling sugar-cane processor by the name of Usina Coruripe Acucar e Alcool SA. Its debt is rated Caa1 by Moody’s Investors Service, a level that is seven rungs below investment grade. Undeterred, investors snapped up 713 million reais of the six-year notes the company sold in November.

The debt offers floating interest rates and is collateralized. The senior tranche paid 3 percentage points above a local rate tied to the Selic and the subordinated notes paid 9 percentage points above the rate. At today’s levels, those rates come to about 7.9% and 13.9%.

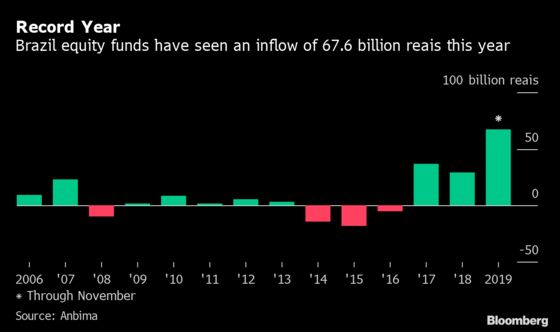

Meanwhile, investors have been pouring cash into hedge funds and equity mutual funds.

Hedge funds raked in over 200 billion reais in the past four years, more than five times the total received between 2006 and 2015. Equity funds took in 67.5 billion reais in the first 11 months of 2019, more than double last year’s haul and the most in a decade.

These flows have helped drive the stock market up 50% in the past two years. In dollar terms, its gain is 10 times that of the benchmark emerging-markets index.

Brazilian equity offerings have almost tripled this year compared to last, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, boosted by government privatizations that led to jumbo deals. And in just the past few weeks, a web hosting company, real estate firms and a burger chain announced plans for debut sales.

One IPO perfectly captures the mood and the moment in the market: last week’s $2.25 billion offering by XP and the 40% price runup over the three days that followed.

XP is the country’s largest stock brokerage and specializes in buying and selling shares for retail investors, a group that for the first time now outnumbers people in prison in Brazil -- 1.5 million to 800,000. Roberto Campos Neto, the central bank president, excitedly touted that factoid at a conference in Sao Paulo last month.

The figure, to be sure, still represents less than 1% of the population. (For some context, more than 50% of Americans invest in the stock market.) And while institutional investors -- mutual funds, pension funds, etc. -- invariably own some amount of stocks, it remains a paltry sum. Teresa Barger, the chief executive officer of Washington-based hedge fund Cartica Management, estimates that they have between 94% and 98% of their money parked in fixed-income assets, a figure she called “shockingly high.”

“That great rotation still has a long way to go,” said Barger, who oversees $2 billion of clients’ money, much of it dedicated to Brazil.

By all indications, though, there will be time for that shift to keep building.

While there have been periods in the past during which Brazilian policy makers cut interest rates only to reverse the move months later once inflation roared back, this time it seems like borrowing costs may stay low for longer. Today’s 3.3% inflation rate is the lowest in two decades, and not even the recent sell-off in the real -- which was triggered in part by the interest-rate cuts -- seems to be sparking concern that consumer prices are poised to surge any time soon.

“The migration of assets from fixed-income investments in Brazil to higher-yield and higher-volatility products has just begun,” said Reinaldo Le Grazie, a former central bank director who in November joined Panamby Capital, an asset-management firm that is starting a hedge fund in Brazil. The fund will invest about 40% of its portfolio in local stocks. “There will be plenty of opportunity ahead.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Aline Oyamada in Sao Paulo at aoyamada3@bloomberg.net;Vinícius Andrade in São Paulo at vandrade3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.