The $1 Trillion Buyback Hysteria May Be Overstated. Here's Why

The $1 Trillion Buyback Hysteria May Be Overstated. Here's Why

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been impossible to miss all the yelling about how stock buybacks are inflating the longest rally in U.S. history.

America’s 500 largest companies are poised to spend almost $1 trillion removing shares from public markets this year, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Apple Inc. recently announced plans to repurchase an extra $75 billion of its stock. And everyone from presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders to Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman’s former chief executive officer, has opined on the impact these purchases have on companies, the market and society.

There’s certainly a lot of cash at stake, but buybacks are not solely responsible for the bull market. First, the billions spent on them are about 1% of all the shares that change hands on U.S. exchanges every year. It’s a big and visible source of net demand, but a small portion of overall trading. Second, a handful of companies are responsible for most of the dollars -- this is not a free-for-all. And third, stock repurchases have probably not come at the expense of investment.

“The narrative that buybacks are evil and are the only thing propping up the market is overstating the case,” says Ed Clissold, chief U.S. strategist at Venice, Florida-based Ned Davis Research Inc. “The other part of the story is that companies have been profitable and investors have gotten more comfortable since the financial crisis being in equities, and that seems to be far more important.”

Cash Cow

Buybacks involve a company gradually bidding for stock in the market or giving shareholders an option to tender their stakes. By removing stock, a company theoretically improves its earnings per share, and can buoy its valuation.

Typically they’re deployed if a company decides that other uses of its cash -- such as strategic acquisitions or business investment -- won’t yield a sufficient return. The problem comes, or so the argument goes, when everyone’s doing it.

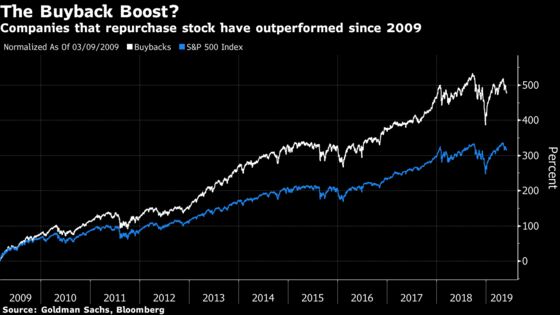

Spending on share repurchases jumped more than 50% to $819 billion in 2018, and is set to climb to $940 billion this year, according to Goldman. That’s a big one-way bet on the stock market, with repurchases boosting valuations to the tune of about 19% over the last eight or so years, according to a study by Ned Davis Research. (The firm subtracted the value of repurchases from the benchmark’s dollar return.)

That sounds like a lot, but the S&P 500 has climbed 166% during the same period and is up 12% this year alone. And that’s if the money used for buybacks just disappeared; the market would be just 2% lower if companies reinvested their extra cash instead of repurchasing stock, the firm says. Yardeni Research Inc. concluded in a March report that buybacks have no significant impact on earnings per share, and a gauge of shares outstanding has fallen just 0.3% a year during the last decade.

Embedded in arguments that repurchases explain the bull market is the idea that if companies weren’t buying, nobody would be. And indeed, on a net basis, subtracting buying from selling, corporations are perhaps the single biggest source of demand for equities. On the other hand, the sprawling U.S. stock market sees an enormous volume of shares go back and forth among buyers and sellers each day. When they represent as little as 1% of value traded, how pervasive are companies in setting prices?

More than $80 trillion of equity trading takes place in America every year, data compiled by Bloomberg show. About 51.5% of that is high-frequency firms, according to Tabb Group data, with the rest divided among groups like hedge funds, retail clients and quants. Buybacks are included in a category of long-only investors that also includes mutual funds and ETFs that together make up 12% of volume. And regulations minimize the impact of repurchases on share prices by limiting when and how much a company can trade.

“It’s mind boggling, but it’s just what the U.S. market does every day,” said Phil Mackintosh, chief economist at Nasdaq. “The equity markets are just so liquid and a lot of people don’t quite appreciate it.”

Who’s Who?

Initial public offerings, which are forecast to raise $100 billion in 2019, and secondary placements further offset some of the buybacks. Goldman found corporations’ net demand for U.S. equities to be about $509 billion last year, with pension funds and mutual funds among those on the other side of that trade. But far from portending a sell-off if corporate money eventually dries up, those sales could reflect portfolios rebalancing after a long rally, according to Ned Davis’s Clissold.

The net number also disguises which companies are actually undertaking buybacks. The financial and technology sectors dominated last year, with virtually no activity in energy, real estate, communication services or utilities among corporate clients of Bank of America Merrill Lynch, which sees a similar trend in 2019. Indeed, 20 companies accounted for more than a third of cash spent on repurchases last year, and almost 70% of their growth, Goldman said in a March report. Apple alone accounted for 14% of the rise in buybacks.

“It is more of a large-cap U.S. story,” says Steven Wieting, global chief investment strategist at Citigroup Private Bank. “If you look at buybacks relative to market cap, there will be less concentration.”

To be sure, arguing buybacks aren’t doing much to lift stocks may do more to buttress than debunk the view that they’re a societal waste. Why blow so much cash if the rewards are uncertain? After all, claims that repurchases benefit people who are already rich tend to be secondary to the critique that the money would be better spent elsewhere -- particularly when a lot of it stems from federal tax cuts.

“When corporations direct resources to buy back shares on this scale, they restrain their capacity to reinvest profits more meaningfully in the company in terms of R&D, equipment, higher wages, paid medical leave, retirement benefits and worker retraining,” wrote Sanders and Senator Chuck Schumer for the New York Times in February.

The duo propose banning buybacks -- which have only been permitted for the last 37 years -- unless a corporation has already invested in its staff.

But Ed Yardeni, chief investment strategist of Yardeni Research, says that’s exactly what buybacks are being used for. Rather than returning money to shareholders, they offset stocks distributed to a company’s employee stock plan, he wrote in a March report.

Other Uses

Repurchases can, however, also mean a bonus for a company’s directors, something that’s drawn the ire of politicians. “A lot of corporate executives are incentivized to improve the price of the stock,” says Tabb Group’s Larry Tabb. “If I as a manager have a stock option, the best incentive for me would be to buy the stock back because that improves the price of my options which then ends up in my pocket.”

Yet companies do seem to be plowing money back into their businesses when it makes sense. Growth investment has won the most corporate cash for the last three decades, and companies increased capital expenditure and research-and-development spending 13% in 2018 to $1.1 trillion, according to Goldman. AQR Capital Management found in a paper last year that investment activity has steadily increased over the last 30 years.

Buybacks may be an easy target but they’re just one way in which companies can use their cash when that’s the best return on investment, says Mike Ryan, chief investment officer for the Americas at UBS Global Wealth Management.

“While everyone’s saying it’s just financial alchemy, I would say it’s probably a prudent deployment of excess cash,” he says. “Buybacks are a function of corporate treasurers making decisions on how they want to deploy capital. If you ask me whether I think this market has been artificially held up by buybacks, I don’t.”

--With assistance from Vildana Hajric.

To contact the reporters on this story: Rachel Evans in New York at revans43@bloomberg.net;Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.