A Battle Over the Future of Energy Plays Out in New York

Stopping Pipelines Helps the Climate Tomorrow—and Creates Headaches Today

(Bloomberg) -- A skinny Brooklyn brownstone was ready for occupants in mid-August. The beds in each unit had comforters, the drawers in the kitchens had utensils, and the living rooms had baskets of toys for the children who were about to move in. “It looks like someone just stepped out to the street to go to the bodega,” Scott Stepp, director of development at Providence House, a nonprofit that provides housing for homeless mothers.

The homes had one problem: Providence House couldn’t get National Grid Plc, the local utility, to hook up the gas to the buildings. That’s because National Grid and New York state are fighting over an underground pipeline—and the future of energy.

National Grid, which provides gas to more than 20 million people, has been at loggerheads with state regulators over a plan to build a new project under the mouth of the Hudson River. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo is backing an ambitious push towards renewable energy sources and has opposed new pipelines for natural gas. Local environmental groups have also mounted an offensive against new fossil fuel infrastructure. National Grid, in response, has resisted turning on the gas for any new customers, including the homeless women and children, without pipeline approvals from the state.

This problem has the potential to play out in cities across the U.S., where the need for new and upgraded gas pipelines meets growing environmental pushback that makes it hard, if not impossible, to expand and improve existing systems. Natural gas was once touted as the greener alternative to oil, and a boom in domestic supply that drove prices down has prompted thousands of households to convert from oil heat. But facing an ever-warming planet, environmental groups and policymakers are pushing harder to move people away from gas and into options like electricity-based heating and cooking, which can help lower greenhouse-gas emissions.

“It really does illustrate the kind of inflection point that we’re at,” says Jackson Morris, eastern region director of the Climate and Clean Energy Program within the Natural Resources Defense Council.

To reach the Paris Climate Agreement goal of limiting global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius, many companies, states and countries plan to zero-out carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. With gas, Morris says, “you get some incremental reductions” in emissions when compared to oil heat, but not enough to make meaningful progress in slowing the pace of climate change. States like New York, Massachusetts, Illinois and California will need to transition to other energy sources, such as wind and solar, in order to meet aggressive emission goals. That’s why governments don’t want to support pipeline infrastructure for a fuel that they’re moving away from.

Planning for a greener tomorrow comes with costs today. In New England, a lack of pipelines now leads to annual winter price spikes. In the last two years, a Boston import terminal has received tankers carrying super-chilled, liquefied natural gas from Russia—a particularly perverse solution since the U.S. is currently a leading global exporter of gas. A lack of infrastructure makes it all but impossible to get enough gas from Appalachia to Boston. In New York, there are plans to transport gas by truck.

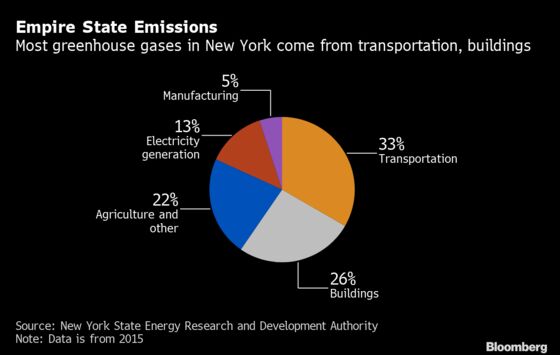

The situation in New York is underscored by the state’s new climate law, which set the nation’s most aggressive goal for getting nearly all electricity from emission-free sources by 2040. The plan also calls for an 85% reduction in economy-wide emissions from 1990 levels by 2050 and creates incentives to phase out oil and natural gas from home heating systems. Buildings account for 26% of New York’s greenhouse-gas emissions, the second-biggest source behind transportation.

But at the moment, New Yorkers are still heavily reliant on gas for energy—40% of statewide electricity comes from gas and 60% of household heat. A lack of good infrastructure is pushing utility companies to import supplies from overseas in a way that makes no economic sense, given it adds transportation costs that consumers ultimately pay. “And it’s bad for the environment,” says National Grid Chief Executive Officer John Pettigrew. His utility would prefer to upgrade pipelines and build new ones. “Lots of people are trying to jump to 2050, but we’ve got 30 years to work these challenges out.”

Environmentalists don’t want to wait. Groups like the Sierra Club and 350.org have been fighting new pipelines, and they’ve had a lot of legal success. Armed with experienced lawyers and record funding, the keep-it-in-the-ground movement has turned its attention to pipelines that require various federal and state permits that are easily litigated. But for this pipeline under the mouth of the Hudson, litigation hasn’t been necessary because state regulators are doing the delaying themselves.

A spokesman for Williams Cos., the company trying to build the pipeline, said in an email that the project is critical for the New York region’s economic growth and blamed delays in gas hookups on the state’s decision to reject a permit.

President Donald Trump has tried to prevent states from being able to block interstate gas lines. The White House announced an executive order in April aimed at short-circuiting state regulators who have held up gas lines by refusing permits. Policy analysts expressed doubt about how effective Trump’s measure would prove to be, and a month later New York rejected the water permit application from Williams.

Some state and local governments are forcing the issue. Berkeley, California, became the first city to tackle it head-on with a ban on gas connections to new buildings, and a handful of other cities such as Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco are considering similar laws. In New York, chaos erupted as opposition to new gas pipelines confronted rising demand from consumers who still want to cook and heat with natural gas.

National Grid projects a 10% increase in demand for natural gas from its customers in downstate New York over the next decade because of economic growth and homes that want to switch to gas from oil heat. Despite Cuomo’s environmental ambitions, the trend toward using electric-based heat and stovetops simply hasn’t taken off yet because it costs more. “We want to connect customers but the system hasn't got the capacity,” Pettigrew says. “Outside the pipeline, there are no long-term solutions.”

As it frantically searched for solutions so the homeless women could move in, Providence House looked into electrifying its buildings. But the retrofit would have cost an additional $200,000 and taken at least nine months. The nonprofit took its case to the state’s Public Service Commission, which monitors utilities in New York, and appealed to National Grid in order to get their gas turned on. It looks like the move is paying off: In late September, the agency ordered National Grid to turn on the gas. In one of the two buildings, homeless mothers are now on track to move in six weeks later than expected; the move-in date for the second home remains subject to a final regulatory approval.

Other New Yorkers are still waiting for gas, with winter looming. Politicians are pressing National Grid to connect more customers, pipeline or not. Last week, Cuomo demanded the utility start supplying gas to the 1,157 homes and small businesses left waiting, threatening the company with millions of dollars in penalties. National Grid said it planned to comply.

That still leaves a backlog of around 20,000 new customers waiting for gas. At Cuomo’s direction, regulators are expanding an inquiry into the utility company, questioning National Grid’s claims that it couldn’t supply gas for customers without access to a pipeline wasn’t scheduled for completion this winter anyway.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Emily Biuso at ebiuso@bloomberg.net, Aaron RutkoffLynn Doan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.