Star Traders’ Stumbles Give Europe a Lesson in Key-Person Risk

Star Traders’ Stumbles Give Europe a Lesson in Key-Person Risk

(Bloomberg) -- Europe’s money managers have learned a tough message from the meltdown at Swiss investment firm GAM Holding AG and the travails of former star stock pickers such as Neil Woodford: A single person can bring down the whole firm.

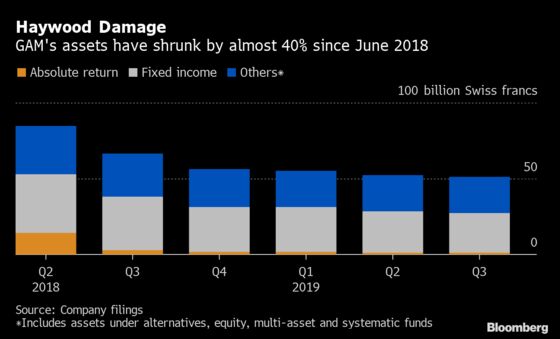

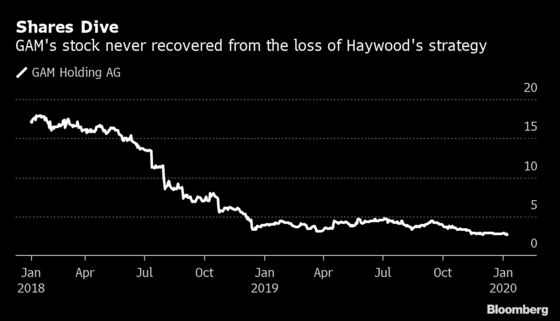

GAM lost almost 40% of its assets and three-quarters of its market value since it suspended Tim Haywood, who ran some of the firm’s biggest bond funds. Woodford, who froze his fund after veering into unlisted equities, has since announced plans to shutter his eponymous investment firm.

These and other fund scares in Europe have shaken the region’s asset management industry to its core, with firms from Invesco Ltd. to Fidelity International moving to limit their exposure to star stock and bond pickers. More than a year after the troubles at GAM started, they’re adding co-managers and beefing up governance to reduce key-person risk.

“It’s no surprise that we have seen many investment firms take action to minimize the impact of key person risk more recently,” said Peter Brunt, an analyst at fund researcher Morningstar Inc. “There is now a greater emphasis on governance within asset managers.”

Star managers have been around since the times of Fidelity Investments’ Peter Lynch or Legg Mason Inc.’s Bill Miller, and their investing prowess is still an advantage today for active managers seeking to fend off cheap index funds. But the risks became all too apparent when, in 2014, Bill Gross abruptly left Pacific Investment Management Co., the firm he built into the world’s preeminent fixed-income manager over four decades. Pimco suffered more than $300 billion in outflows following his departure.

“Key-man risk is one of several factors which we must consider when it comes to our responsibilities managing a fund,” said Mike Webb, chief executive officer of Rathbone Unit Trust Management in London.

‘Absolute Return’

Rathbone last year named a co-manager at four multi-asset funds run by David Coombs. In October 2018, shortly after the Haywood suspension, the firm already named a co-manager for its Rathbone Income Fund. While one manager will still have seniority in the co-structure, the idea is to commit more resources to the investing process and have a backup in place if needed, Webb said.

At GAM, Haywood wasn’t the only manager of the absolute return bond strategy at the center of the firm’s troubles, but he was it’s public face. His funds reached their peak in the years directly after the the financial crisis and GAM was capitalizing on his reputation to bring in assets. By the time of his suspension, Haywood oversaw GAM’s second-biggest strategy.

Because of his success, he enjoyed a large degree of autonomy, operating almost like a separate firm out of London, hundreds of miles away from GAM’s headquarters in Switzerland. With historically low interest rates limiting returns after the crisis, he used his freedom to venture further into riskier, less liquid holdings in search for an edge. That’s where the troubles started.

It was a strategy other fallen star managers also pursued, and which proved ill-suited for funds that promise daily liquidity to clients. H2O Asset Management, for instance, the London firm co-founded by bond maven Bruno Crastes, bought thinly traded debt tied to Lars Windhorst, a financier with a history of troubled investments. When Morningstar questioned the “liquidity and appropriateness” of such holdings and suspended its rating on one of the firm’s funds, clients pulled $8 billion in a matter of days.

Search for Yield

Neil Woodford, the famed U.K. stock picker, started veering more into unlisted and smaller quoted equities after he set up his own firm in 2014. When performance faltered and clients started to pull out, he was forced to freeze his LF Woodford Equity Income Fund because he couldn’t meet redemptions. In mid-October, he was ousted as manager of his flagship fund and announced he would shutter his investment firm.

More than five years earlier, Woodford had triggered a flood of redemptions at his former employer Invesco Ltd. when he quit as manager of the Invesco Perpetual High Income Fund, where he earned his reputation as one of the country’s best stock pickers. Now, his own firm had fallen victim to the same key-person risk, having been built entirely on the investing acumen of its founder.

The discovery that Woodford had ventured into holdings that were difficult to sell even spilled over to his former employer, Invesco. His successor Mark Barnett had the rating on two of his funds cut by Morningstar because he, too, had drifted into harder-to-sell assets. Barnett’s Invesco High Income fund suffered the biggest outflows in more than five years in November, the month Morningstar downgraded his funds.

Style Drift

Invesco swiftly moved to contain the damage. In late November, it shook up the leadership of its U.K. equities funds, appointing Martin Walker to work alongside Barnett. While both continue to run their respective funds, the two are now splitting management duties.

“There have been too many instances of control issues, style drift or just the departure of key staff that have rocked investors,” said Stuart MacDonald, who helps funds raise money as managing partner at Bride Valley Partners. “With various issues that have arisen with well known names in Europe, focus on operational due diligence should be of utmost importance” for investors.

Other firms that have acted to reduce key-man risk include Fidelity International. The firm, which is owned by management and members of the Johnson family that also owns Fidelity Investments in the U.S., introduced more co-managers at some of its stock funds last year in a conscious move toward more team-based investing.

Having co-managers “helps to address key person risk, an increasingly important topic for our clients,” said a spokesman for the company. “We firmly believe clients benefit from a strong and deep team of investment professionals to manage their portfolios.”

Even co-managers, however, are no guarantee that firm can avoid a run on funds should a key person stumble. At GAM, Haywood had two co-managers who stood by to keep running the funds, but the announcement of his suspension still triggered a run, in part because it wasn’t clear what exactly Haywood was accused of doing.

The decision and how it was communicated has since been a matter of much debate. Clients and analysts questioned why GAM only disclosed the issue eight months after the probe began, and why it didn’t give more details on what led to the suspension. Others, like Bluebell Capital Partners, an activist investor that took a small stake recently, say the company overreacted, given how sensitive any suggestion of wrongdoing by a key man is.

‘Kill a Fly’

“They used a bazooka to kill a fly in the boardroom,” said Giuseppe Bivona, co-founder of London-based Bluebell.

At H2O, Crastes took a different route, pledging not to freeze any funds. Instead, he marked down some holdings to fire sale prices, cutting their value by 50% or more even though the debt traded at much higher prices the same day. Crastes was effectively punishing investors for wanting out, something other firms typically avoid in the interest of treating all clients the same. In the end, H2O contained the crisis, but its owner, Natixis SA, has since moved to strengthen governance at its asset management arm.

GAM, meanwhile, was trying to do right by its clients but it was losing the battle for investors’ trust. During an analyst call on July 31, 2018, analysts pushed Chief Executive Officer Alex Friedman to explain what had prompted Haywood’s suspension. The CEO refused to go beyond the company’s statement. When analysts pushed him again, he fired back, saying he had disclosed as much as he could.

A year after Haywood’s suspension, GAM finished liquidating his $7 billion Absolute Return Bond Fund. Clients received all their money back, even with a small profit, validating the decision to freeze the fund to avoid a fire sale of assets.

For the CEO and his firm, however, the damage had been done: Friedman was replaced in November 2018. GAM unsuccessfully tried to sell itself and is now facing calls from activists including Bluebell for a review of parts of the business and a reshuffle of the board.

“It caused a lot of collateral damage and in this case the collateral damage was the shareholders,” said Bivona.

To contact the reporters on this story: Nishant Kumar in London at nkumar173@bloomberg.net;Patrick Winters in Zurich at pwinters3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Shelley Robinson at ssmith118@bloomberg.net, Christian Baumgaertel, Dale Crofts

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.