Saudi Prince’s Cultural Revolution Comes to Scotland

Saudi Prince’s Cultural Revolution Comes to Scotland

(Bloomberg) -- In the Scottish Highlands, where rugged mountains collide with the Atlantic, Lewis Gibson reaches into a bucket of brown pellets and scatters a handful into the gray salt water of Loch Leven. Under the surface, there’s a flurry of activity as thousands of salmon jostle for a snack.

“They can feed better on an overcast day rather than a bright blue sunny one,” says Gibson, 30, as drizzle and 13 degrees Celsius (55 degrees Fahrenheit) gave way to patches of sunshine.

The scene on a June day hardly feels like summer, and couldn’t contrast more with the arid heat of the Middle East. But if all goes to plan, some of the fish being bred at marine farming company Mowi ASA’s site in the sea loch between Glencoe and Ben Nevis may end up being eaten in Saudi Arabia.

The kingdom is a frontier market for fish breeders that’s expanding rapidly after Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman included healthy living in his plan to transform Saudi society and the economy.

The aim is to change dietary habits in a place where lamb dominates and hypertension, heart problems and diabetes affect one in five people. “Social changes will help move consumption toward seafood,” said Ali Al Shaikhi, director general of the kingdom’s General Directorate of Fisheries, which is running a public awareness campaign.

Like the crown prince’s “Vision 2030,” the target is ambitious: To almost double per capita fish consumption to 13 kilograms (29 pounds) by the end of next year and then to 22 kilograms, the global average, by 2030. The fisheries department has started a certification program that brands fish from local aquaculture farms and sells the “trusted” product packaged for ease of use, said Al Shaikhi.

That’s an opportunity, says Jamie McAldine, the account manager at Mowi responsible for the Middle East who is based just north of Edinburgh. The company, which has 50 farms in Scotland and is by far the nation’s biggest salmon producer, is currently going through the paperwork with the Saudi government to become an approved supplier, he said.

“The process is a bit painful, but we’ll get there,” said McAldine. “As soon as we become approved, they’re ready to take the fish. We’ll be sending at least one order per week and hoping to build on that.”

Norwegian salmon is already there. The nation dominates the global salmon industry, accounting for about half the world’s production. Scotland makes up less than 10 percent, and many of its farms are owned by Norwegians. Mowi, for one, is listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange.

Norway started looking at Saudi Arabia four years ago and made inroads after a group of executives from salmon companies attended a food expo in Riyadh in November. There, they heard from Saudi officials about the focus on healthy living.

The outcome has been stunning. Seafood exports to Saudi Arabia, mainly salmon, grew by 74% in monetary value and 60% in volume in the first four months of this year compared with the same 2018 period, according to the Norwegian Seafood Council, a marketing board for the industry. Fifty Norwegian companies now sell to Saudi Arabia, up from a handful previously. “Saudi Arabia is growing very nicely,” said Ingelill Jacobsen, manager for emerging markets at the Norwegian Seafood Council.

McAldine said it was common for Norway to blaze the trail in a new market. Mowi’s Norwegian business has already been selling there. But Scottish salmon—smoked or fresh fillets—is considered a premium product, he said. It’s the U.K.’s biggest food and drink export after whisky.

The Scottish government decided five years ago to push fish into new markets in Asia and the Middle East, according to John Carlill, senior international trade specialist at Scottish Enterprise, a business agency.

The model market for salmon is the United Arab Emirates, where imports from Scotland have soared in recent years. UAE sales more than doubled in the first four months compared with the same period of 2018, to 2.1 million pounds ($2.7 million), U.K. customs figures show. By comparison, Saudi sales were a mere 172,400 pounds, little changed from a year ago.

In the 40 Celsius heat of Riyadh, Al Shaikhi said change is coming. As well as bringing salmon into the country, a Saudi investor has been awarded a license to develop a farm in the kingdom. Construction is expected to start next year north of the coastal city of Jeddah. Another potential salmon farm is being considered for Neom, the Saudi crown prince’s futuristic city on the Red Sea, he said.

The Scots say that’s ambitious, given that sea water needs to be kept between 9 and 14 degrees—the reason inlets and fjords in Norway, Scotland and Chile dominate the industry. The water in Loch Leven on a visit in mid-June was 11 degrees.

At that time, the farm was in a “harvesting” period, when the fish are sucked out of the cages in the water through a tube to be stunned and bled onshore in a facility next to Mowi’s offices there.

It takes 10 seconds to kill them and less than a minute to get them on ice ready for transport. Within 48 hours they can be in the Middle East, taken first by truck to the nearby hub of Fort William and then down to Glasgow for flights to Dubai or London Heathrow and on to Saudi Arabia.

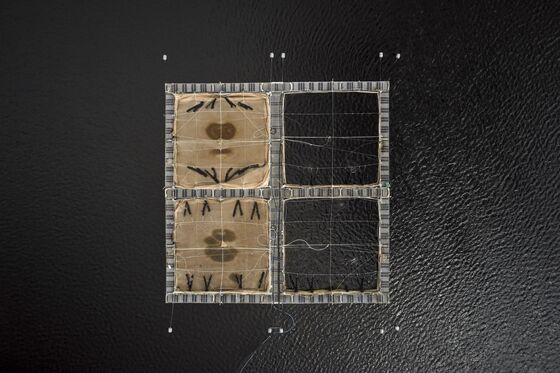

Gibson, the assistant manager at the site, said 20,000 fish can be kept in 16 pens, each 24 square meters in size and 15 to 21 meters deep. Underwater cameras monitor them. He looked at this computer as the weather changed for a third time in 15 minutes. There were 165,854 fish with an average weight of 5.1 kilograms, he said.

“For me, it’s farming,” said Gibson, whose father is a deer stalker in the Highlands. “I’ve looked after the fish,” he joked, “and then I look and see that they’re going to happy places to be eaten by lovely people.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Sillitoe at psillitoe@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.