Haven Assets Needed. They Don't Even Need to Be That Safe.

Safe-Haven Assets Needed. They Don't Even Need to Be That Safe.

(Bloomberg) -- Corporate debt, collateralized securities and even stocks may not sound like the sort of assets money managers would seek out for their haven qualities. Yet a slide in global bond yields is forcing investors to look outside of the usual refuges as they hunt for stable assets that provide at least a modicum of return.

Gene Tannuzzo, who oversees the $4.8 billion Columbia Strategic Income Fund, says he’s adding investment-grade corporate bonds from Europe for the extra yield. Sarah Lange, a senior fixed-income portfolio manager at Pentegra, is “begrudgingly” seeking out asset-backed debt. Craig Pernick, the head of fixed income for Chevy Chase Trust Co., was even tempted recently by a non-convertible dollar bond from China’s Weibo Corp.

“Everybody has their own definition of safe haven, and it seems people are loosening that definition in search of yield,” said Pernick, whose firm manages $30 billion in assets. The challenge these days is “not falling into the trap of changing strategy too much.”

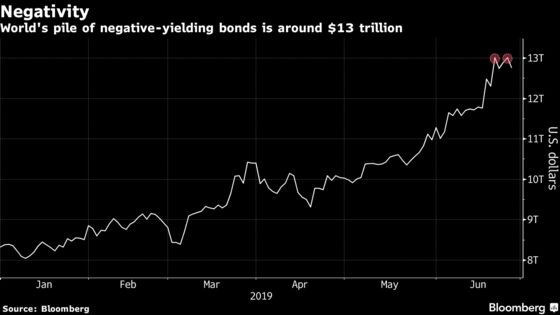

It’s the new reality for investors dealing with the fallout from dovish turns by central banks in the U.S. and Europe, which have pledged to act to ward off an economic slowdown and want to boost stubbornly low inflation toward their target levels. Money managers staring down 10-year Treasury yields around their lowest since 2016 and some $12.7 trillion of global negative-yielding debt that they’d have to actually pay for the privilege of owning are left with few options beyond easing their standards. As a result they’re turning to assets that might seem relatively riskier, but are potentially sheltered from global events while also offering extra yield.

This year’s global bond rally broadly reflects persistently low inflation rates, investors’ expectations that a recession is on the horizon and the possibility that central banks may not be able to do enough to spark growth or consumer-price increases.

But U.S. government bonds have gotten an extra boost from demand generated by the negative yields in Europe, according to Brett Wander, who oversees more than $190 billion in assets at Charles Schwab Investment Management in San Francisco. As of Thursday, the 2.01% payout on benchmark 10-year Treasuries was about 70 basis points above its record intraday low reached in 2016.

Bank of America strategists are warning of the risks of “Japanification” of yield curves throughout much of the developed world, resulting from an extended period of subpar growth, slow inflation and low rates. That pattern already seems to be taking hold in Europe, and Bank of America sees a risk that yields will stay persistently low across much of the continent, as well as the U.S. and Japan.

A world starved of yield “implies a tectonic shift in asset allocation,” with greater appetite for emerging-market investments, said Bruno Braizinha, BofA’s director of U.S. rates strategy.

For Tannuzzo, deputy global head of fixed income at Columbia Threadneedle Investments in Minneapolis, finding a safe and positive-yielding investment means sorting through investment-grade corporate bonds in Europe. While the euro-denominated notes carry lower nominal yields than equivalent U.S. securities, he points out that they actually have better returns once factoring in the conversion to dollars.

European corporate credit yields sank to a record low this week on a flood of demand from investors, but Tannuzzo sees them dropping even further if the European Central Bank begins purchasing more corporate bonds.

At Pentegra, a White Plains, New York-based pension fund that manages $15 billion in assets, Lange said she favors out-of-the-mainstream choices in securitized products: “new issues, esoteric asset streams, private deals that won’t get a whole lot of publicity.”

“I’m not quite a believer that we’re going to stay at these levels, at these low rates, but now I have to invest a little bit, but begrudgingly,” she said during a June 20 interview at a conference in Philadelphia. With a 10-year Treasury yield that has a better chance of getting to 1.25% than 2.40%, “I have to just throw in the towel and I have to start spending some of my cash.”

Pernick of Chevy Chase Trust said he and his colleagues “spent a lot of time” this week looking at the five-year note from Weibo, a Chinese social media company, that yielded 1.725 percentage points over Treasuries as of Wednesday. “In the end, we just didn’t have the comfort level at that spread to add it,” he said. “The risk-reward was not there.”

Guy Haselmann, chief executive officer of FETI Group LLC, says he’s hearing many portfolio managers rely on dividend-paying stocks as a form of fixed income. Indeed, the iShares U.S. Real Estate ETF, which carries an indicated yield of about 3.1%, saw its biggest inflow since February 2018 on Monday as investors put $294 million into the fund, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Haselmann, whose Summit, New Jersey-based company works with managers to generate ideas, sees a revival of the TINA (“there is no alternative”) trade, which results in a less-than-ideal portfolio allocation usually made up of stocks because other asset classes offer worse returns.

“What could go wrong?” he asks.

--With assistance from Emily Barrett and Tasos Vossos.

To contact the reporter on this story: Vivien Lou Chen in San Francisco at vchen1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.