Researchers Debate Whether Global Emissions Have Peaked

Researchers Debate Whether Global Emissions Have Peaked

(Bloomberg) --

Have global emissions from energy peaked?

The short answer is probably not. A slightly longer answer is probably not, and don't let the coronavirus fool you.

Cautious optimism gripped the world climate conversation last week when new data showed that global energy emissions remained flat in 2019 after two prior annual increases.

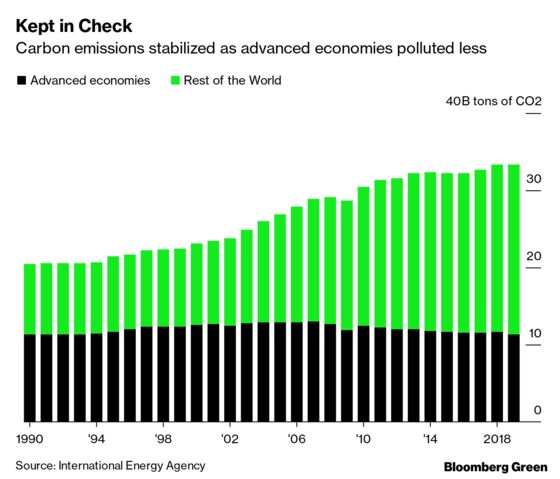

New energy and old energy canceled each other out, leaving no net change in overall emission levels, according to preliminary data from the International Energy Agency. U.S. and European energy emissions fell dramatically on the further demise of coal and rise of renewables. Japan returned to using more carbon-free nuclear power. Eighty percent of the increase in emissions last year came from Asia, where coal use is still expanding and makes up more than half of energy use.

But these two factors—falling emissions in the developed world and the growing emissions from the developing world—are not the only dynamics at play. And in a situation where two massive, inertia-heavy competitors are running neck-and-neck, small factors take on disproportionate influence.

Two days after its first look at 2019 emissions data, the IEA released its monthly oil market update, which projects that the “widespread shutdown” of China’s economy, caused by the coronavirus, will cause global oil consumption growth to drop to the lowest level since 2011. Emissions would consequently fall with it. Oxford Economics projects the outbreak could slow global GDP growth this year by 0.2%, to 2.3%. Given the shifting but strong ties between economic growth and pollution, a slowdown increases the chances for 2020 emissions to dip lower than 2018-2019—completely independent of trends in energy use. And as the economy recovers in the next couple of years, it'll be more likely to reach a higher level of emissions than 2020, just because the dampening effect of the virus—we hope—will no longer be a factor.

The tragedy of the coronavirus is only the most visible phenomenon that could nudge emissions this year. Other factors range from changes to how nations and the IEA measure emissions and changes in global political leadership.

These sources of noise help explain why researchers need a long time to be able to say if emissions have actually peaked, said Kelly Levin, senior associate at the World Resources Institute's global climate program.

“We have one year of data, which could be a blip,” she said.

Levin said there's a way even a perceived slowdown in emissions could backfire. Nations attending this year's UN climate talks may be inclined to reduce their ambition to slash pollution if they have an unrealistic belief that emissions have already turned the corner. "We can't get complacent," she said.

And when the pinnacle of pollution does come, the party shouldn’t last long. The UN Environment Program concluded last year that greenhouse gas emissions—all of them, not just from the energy sector, and not just CO₂—need to crash by 7.6% a year until 2030, to have a shot at keeping the world from warming above 1.5°C. It’s looking increasingly impossible to meet the Paris Agreement’s lower-end target.

So, have global emissions peaked? It's unlikely and impossible to say for sure. Which leaves us with another question, posed this week by Jane Flegal, an adjunct faculty member at Arizona State University's School for the Future of Innovation in Society: Have we reached peak hype about peak emissions yet?

Eric Roston writes the Climate Report newsletter about the impact of global warming.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Josh Petri at jpetri4@bloomberg.net, Emily Biuso

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.