Ray Dalio Is More Famous Than Ever and Delivering Subpar Returns

It’s lagged behind peers, and a roughly 2% decline in 2019 is shaping up to be one of its worst years on record.

(Bloomberg) -- The biggest hedge fund in the macro game, a $40 billion beast, is looking a lot like an also-ran.

It’s lagged behind peers over the past eight years, and a roughly 2% decline in 2019 is shaping up to be one of its worst years on record, according to people familiar with its performance. Yet the behemoth, Pure Alpha II, is the flagship of none other than billionaire investor Ray Dalio.

That’s right, Ray Dalio -- founder of Bridgewater Associates and, to his many admirers on and off Wall Street, celebrated author of “Principles,” his 600-page manifesto for success that has sold 2.2 million copies since its publication in September 2017. The tome, an unlikely crossover hit that’s been praised by celebrities from Bill Gates to Sean “Diddy” Combs, was recently turned into an illustrated version for kids.

Rarely has a money manager’s stature with the investing public seemed so at odds with their recent record as an investor. With “Principles” still in the spotlight, Pure Alpha II’s performance usually goes unmentioned.

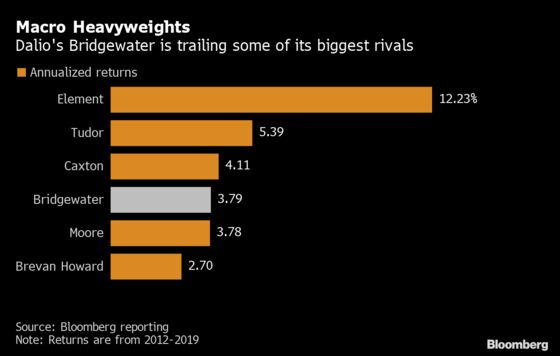

Following peak returns of 45% in 2010 and 25% in 2011, the fund’s performance has struggled. Dalio’s flagship has returned an annualized 3.8% since the start of 2012, even with a 15% gain last year. That places it behind standouts such as Jeff Talpins’s Element Capital Management and Tudor Investment Corp. for the period, and it’s the same story over the past three years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Of course, Bridgewater isn’t alone in trailing the markets for much of this decade. In recent years, macro managers have found it hard to make big profits trading in their usual fare of government bonds, currencies, commodities and stock indexes. In their heyday, these funds regularly produced double-digit gains. Bridgewater has racked up an annualized 11.4% since its start in 1991. (Paul Tudor Jones and Louis Bacon, who both started in the 1980s, have done even better.)

The difference between Dalio and his peers is investor response to the recent performance. In many cases, clients have fled. Perhaps the hardest hit has been Brevan Howard Asset Management, where assets peaked at more than $40 billion in 2013. It now manages about $7.5 billion. Bacon, who founded Moore Capital Management, said last month he was stepping back from his duties in part because of low returns.

By contrast, Pure Alpha II is closed to new capital and has a waiting list of about $5 billion, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. Investors credit Dalio’s reputation, along with savvy marketing and first-rate customer service.

It’s easy to see the allure of Dalio and his firm. While outsized earlier successes created a stellar reputation, there’s also the mystique of the unorthodox culture at Bridgewater. Dalio runs the industry giant nestled in the woods of Westport, Connecticut, following a set of about 200 principles, which are the subject of the bestseller. The most central is “radical transparency,” a demand that employees be brutally honest with one another. All meetings are taped and archived for future study and discussion.

“Bridgewater has just become such an institutional name,” said John Culbertson, president and chief investment officer of Context Capital Partners, which invests in startup managers. “It’s very hard to get fired for allocating capital to Bridgewater because of who they are and their reputation.”

A Bridgewater spokesman declined to comment for this story. On Tuesday, the firm said Eileen Murray, co-chief executive officer, was leaving. David McCormick will become sole CEO. Since Dalio ceded day-to-day management in 2011, five people have held the title of CEO or co-CEO.

Bridgewater’s firmwide assets now stand at about $160 billion, including hedge funds and lower-fee products, a figure that’s stayed roughly constant for most of the decade. As founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, Dalio has an aura akin to that of Warren Buffett or Bill Gross, the one-time bond king, at the height of his fame. Since the publication of Dalio’s book, he’s been mentioned more than 9,000 times in the media, according to a Nexis search.

While Dalio never tells anyone other than clients how his portfolio is positioned, Bridgewater’s moves in the markets -- real or perceived -- are routinely parsed by traders hunting for any edge. Investors eagerly await his latest pronouncements on everything from China’s Communist Party to U.S. President Donald Trump.

Bridgewater has about 200 people overseeing client relationships, one for every 1.7 investors, and acts as a money-management consultant that will analyze the riskiness of an entire portfolio. It also publishes daily musings on markets or the economy that investment heads say helps them look smart when they appear before their boards.

This year, Bridgewater’s losses were fueled by bearish wagers on global interest rates, particularly in Europe and the U.K., according to people familiar with the matter. The firm is also bullish on global equities, and expects to remain so.

Pure Alpha II’s decline comes as many of its macro peers have made money this year. Element returned about 8.4% through October and Greg Coffey’s Kirkoswald Global Macro Fund climbed almost 29% in that period. Andrew Law’s Caxton Associates has jumped about 17%.

Yet for many investors, Dalio’s reputation is undimmed -- even for people like Michael Rosen, chief investment officer for Angeles Investment Advisors, which manages money for endowments and foundations. While Rosen dropped Bridgewater several years ago because he doesn’t think a macro strategy makes sense in the current environment, it didn’t affect his view of the founder.

“I think Ray is a genius,” said Rosen. “What he built is extraordinary and I think his legacy is secure.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Katherine Burton in New York at kburton@bloomberg.net;Melissa Karsh in New York at mkarsh@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sam Mamudi at smamudi@bloomberg.net, David Gillen

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.