Once ‘Toxic,’ Floating-Rate Company Bonds Find Buyers Again

Once ‘Toxic,’ Floating-Rate Company Bonds Find Buyers Again

(Bloomberg) -- With bond yields having plunged over the last month, money managers from Invesco to American Century are making a surprising move: they’re buying more floating-rate corporate debt.

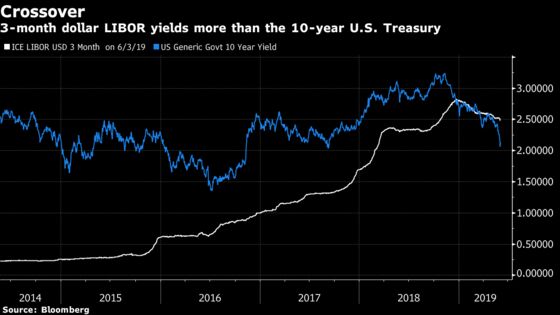

They’re profiting from an unusual twist in the bond markets known as an inverted yield curve, where floating-rate notes can now pay bigger coupons than bonds maturing in five years because short-term rates are higher than longer-term yields. Banks and other financial companies are tapping into that demand by selling more floaters, with issuance topping $15 billion last month, more than seven times April’s level, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The money managers scooping up these securities are betting that the Federal Reserve won’t cut interest rates much this year, if at all. But even if the central bank does loosen the money supply, floating-rate notes are offering higher yields than their fixed-rate equivalents at least for now. The average floater paid a coupon of around 3.1% on Tuesday, compared with around 2.86% on a 3-to-5 year note, according to Bloomberg Barclays index data.

“Sentiment is shifting where it’s no longer toxic to own floating-rate securities,” said Matt Brill, head of U.S. investment-grade credit at Invesco Ltd., who has been buying the notes.

Floating-rate corporate bonds have gained around 2.6% this year including interest payments and increases in market value, according to Bloomberg Barclays index data. That’s a turnaround from the last quarter of 2018, when they lost 0.6%.

Shifting Trend

For months, some investors have shied away from the securities. Floating-rate notes accounted for just 4% of investment-grade corporate bond offerings over the first four months of 2019, far below last year’s 15%. Money managers believed that the Fed was nearing the end of its tightening campaign, so they became less interested in notes like floaters that benefit from rising rates.

The Fed is still expected to avoid hiking rates further, and debt markets are now bracing for as many as two rate cuts this year, which is normally not when money managers start reaching for floating-rate notes. But floaters offer relatively high yields now thanks to the inverted yield curve, and at least some investors are skeptical that rate cuts are coming.

“We’ve had a strong position in floating-rate exposure for quite some time and are enjoying it,” said Charles Tan, co-chief investment officer of global fixed income at American Century Investment Management Inc. “I do see us gradually cutting that if we believe the Fed is closer to cutting rates, but don’t think that’s anytime soon.”

Some investors are more worried about possible rate cuts, and the attendant declines in floating-rate benchmarks like the London interbank offered rate. Historically, an inverted yield curve signals that a recession is coming. Trade tensions are rising, with U.S. President Donald Trump signaling that a deal with China is unlikely near term, and talking about new tariffs on Mexican goods. That may be having an impact on the U.S. economy: a measure of U.S. manufacturing activity fell in May to its lowest level since September 2009, a report said this week.

And even with the big jump in floating-rate issuance in May, the securities have accounted for just around 6% of corporate bonds sold this year. The market itself, with about $300 billion outstanding, is just a small fraction of the more-than $5 trillion fixed-rate corporate bond market.

“With Libor potentially going lower, buying floaters is not something I’d be entertaining,” said Brian Kennedy, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles & Co.

Bank Offerings

Much of the issuance in floating-rate debt is coming from banks, which tend to be savvy about finding the cheapest possible funding. Callable bank bonds account for about a quarter of this year’s supply of floaters. The notes are generally being sold by the operating entities rather than their holding companies, and tend to be relatively short dated, maturing within two years.

The potential for rate cuts is prompting some companies to look at selling floating-rate debt again to potentially get cheaper funding costs, said Stephen Philipson, head of fixed income and capital markets at U.S. Bancorp. And if companies are paying high enough yields now, investors will buy the notes, said Scott Kimball, a portfolio manager at BMO Global Asset Management in Miami.

“At some point, investors will concede the risk that rates may decline,” Kimball said.

--With assistance from Brian Smith.

To contact the reporters on this story: Natalya Doris in New York at ndoris2@bloomberg.net;Molly Smith in New York at msmith604@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at ngammeltoft@bloomberg.net, Dan Wilchins, Boris Korby

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.