Old-Fashioned Indicators Have Been Pretty Useless for Investors

Strategies reliant on signals sent from America’s industrial underbelly had a particularly awful showing.

(Bloomberg) -- Did you shun stocks in 2019 based on a century-old forecasting tool known as Dow Theory? Run screaming from the market because of ever-worsening readings in a gauge of factory output? Or maybe you sold short as freight shipments slid to some of the lowest levels in a decade.

You probably wish you hadn’t, in retrospect. Last year was a bad one to get wrong. The S&P 500 surged 29%. Strategies reliant on signals sent from America’s industrial underbelly had a particularly awful showing.

While millions of people remain employed by the old economy, devotion to indicators tied to its health has been something less than a route to riches during the latest leg of the bull market. Analysts are asking whether American industry has evolved so far away from plants and machinery over the last three decades that once-tried-and-true investing signals are losing their pull.

“Manufacturing is not as important as it was in the past,” said Chris Gaffney, president of world markets at TIAA. “The global economy is not as dependent on those numbers.”

Few trends in the economy were noted with as much displeasure last year as the deterioration in manufacturing. But if you let all the paranoia convince you to sell, the mistake turned out to be a costly one.

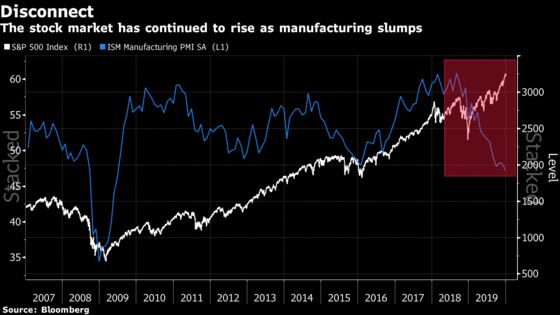

The ISM Manufacturing PMI fell below 50 (the level that divides expansion from contraction) in August and stayed there the rest of the year. The S&P 500 closed lower on all but one of the reporting days since, posting an average decline of 0.6%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. But whoever sold has missed out on a 16% rally over the past five months.

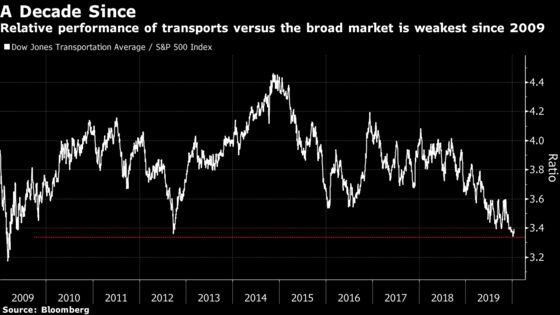

Or take Dow Theory, which says that unless a rally in industrial stocks is accompanied by one in transportation stocks, you should steer clear of the whole market. Except for last year, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average climbed to records 22 times to its counterpart’s zero, and sitting out would’ve cost investors a combined $6 trillion.

Underperformance in the transportation gauge -- stuffed with railroads, global shippers, and airline companies -- is nothing new. Over the last five years, Dow transports have returned 38% including dividends, less than half of the S&P 500’s 81%. That recently pushed a measure of relative performance for transport stocks versus the broader market to a decade-long low.

“We haven’t really gotten the transports ever to go above a significant high point,” said Richard Moroney, the editor of the Dow Theory Forecasts newsletter and chief investment officer at Horizon Investment Services in Hammond, Indiana. “It wasn’t like they were breaking down and giving you a bearish indication, they just weren’t confirming the bullish indication. You want to use it in line with other indicators.”

Last summer, strategists at Morgan Stanley highlighted the Cass Freight Index, which in essence measures the flow of goods through shipments, as underpinning a bear case. At the time, Mike Wilson, the firm’s chief U.S. equity strategist, cited the metric as an input to call for a 10% correction in the third quarter. The S&P 500 fell 6% a month later before bouncing.

To be sure, instead of being wrong, all three of these indicators may just be early. But the divergence is a reminder to investors that nothing should be viewed in a vacuum. Manufacturing now makes up just 11% of gross domestic product in the U.S., the smallest share since 1947. And academic studies suggest the economy and stocks have virtually never been more disconnected.

A working paper by faculty from the MIT Sloan School of Management, the Haas School of Business at the University of California Berkeley, and New York University, finds that over the past three decades, economic growth has accounted for just 24% of share-price appreciation, compared with 92% for the 36 years prior.

Rather, what the authors call “factor share shocks” -- mainly the fruits of innovation, such as changes in the concentration of industries and growth of technology -- have been the “engine of market growth,” accounting for more than half the rise in more recent years.

Technological change and the rising sway of intangible assets like intellectual property have altered the market in countless ways. Combined, the value of the two largest American companies now exceeds that of the entire Russell 2000. Almost a quarter of the S&P 500 is now technology stocks, more than triple the share three decades ago. Last year, a quarter of the benchmark’s returns came from five companies alone -- Apple Inc, Microsoft Corp, Alphabet Inc, Facebook Inc, and Amazon.com Inc.

Maybe there’s a better way, then, to use certain pockets of the stock market as a window into the economy and a harbinger of what’s to come for equity prices. Some investors point to semiconductors as a proxy for growth, since they’re used in products from computers to cars to household appliances.

“The modern economy is powered by semiconductors,” said Tom Essaye, a former Merrill Lynch trader who founded “The Sevens Report” newsletter. “Semiconductors are extremely important and that’s one of the things I put, from a short-term standpoint, on the top of my screens to watch as far as general market momentum.”

Still, Essaye isn’t ready to toss Dow Theory from his toolkit.

“Of course the economy has changed a lot since Dow Theory was created 100 years ago,” he said. “But at the same time, it’s still one of the oldest and most time-tested technical tools that we have.”

--With assistance from Vildana Hajric.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.