Oil Companies Are Unpopular Because They're Introverts

Oil Companies Are Unpopular Because They're Introverts

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It is said that you can’t manage what you can’t measure. Measuring the wrong thing can be just as bad, though. Especially if, as in the case of the oil business, what’s being measured is each other.

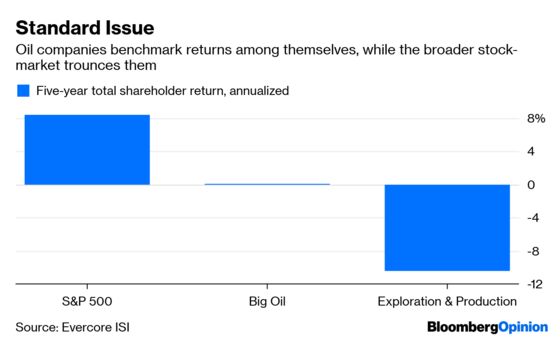

Without wishing to harass the afflicted, I wrote the other day about how desperately unpopular the energy sector is among investors. Remarkably, its pariah status has been cemented further in the brief interlude since. As of Thursday morning, its weighting in the S&P 500 index stood at just 5%, the lowest since at least 1990.

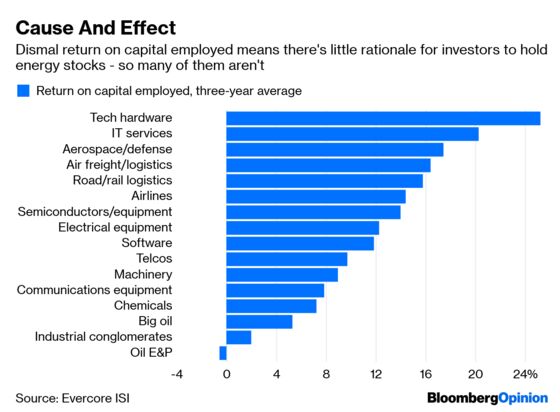

There are clouds hanging over the sector’s future, be it generic things like trade wars or specific challenges like surging shale supply and climate change. But there is also a pernicious legacy of excessive investment, lousy returns on that investment and, consequently, little cash making its way back to investors. At the heart of this is a compensation culture that has long encouraged growth at all costs and skewed rewards in favor of management. And at the heart of that is something meant to keep everyone aligned and on their toes: total shareholder return.

The bulk of executive pay, roughly two-thirds on average, consists of long-term awards like restricted stock units that vest over time. These awards are tied overwhelmingly to total shareholder return, which measures the gain or loss an investor makes from a stock’s performance, as well as any dividends in a certain period of time. Doug Terreson, the lead analyst on the integrated oil sector for Evercore ISI, has been tracking pay trends in detail for several years. Based on the latest proxy filings, he calculates relative total shareholder return determines 56% of long-term pay for CEOs at the majors and 81% for those running exploration and production companies.

That word “relative” is all important.

Boards at oil companies choose a peer group and then measure how their firm’s stock performed in relative terms when setting pay. What that means, of course, is that the whole sector can do terribly, but if the company’s stock was the best of the worst, then the CEO can still be rewarded handsomely. Taking just a second to remind ourselves that energy has slumped to 5% of the stock market, the problem with this Möbius-strip approach to compensation becomes crystal clear.

The sector stands out in this regard. Terreson writes that while almost every materials, technology and industrial company uses the S&P 500 as a comparison and/or measures of absolute value in setting CEO pay, “these features are conspicuously absent from Big Oil and E&P CEO pay plans.” Not unrelated to this, the industry lags in return on capital, too:

Chevron Corp. is the only one of the oil companies Terreson tracks that uses the S&P 500 as a peer in setting long-term pay, albeit with a weighting of just 20% in the total shareholder return compensation bucket (the other 80% uses its big oil peers).

One objection raised against benchmarking relative to the S&P 500 is that oil’s volatility just means it’s different from other industries and makes it hard to normalize for commodity prices in setting CEO pay. But this is undercut by two things. First, there is ample empirical evidence that oil-sector compensation rewards management in the good times but shields them when the cycle turns down. Moreover, if companies can normalize for oil prices in drawing up capital budgets, then it isn’t clear why they can’t do so when setting incentives for management.

But back to that 5% figure. Because it renders debates about the theoretical pluses and minuses of using the S&P 500 as a benchmark moot. Quite clearly, investors are already using it as a benchmark. This reflects a broader change, as the mindset has switched from concerns about energy scarcity to expectations of abundance. Oil’s x-factor has been lost, as current insouciance in the face of rising geopolitical tensions captures, making energy just another sector competing among many. The longer oil companies remain wedded to using each other to judge how they’re doing, the more they will merely validate investors’ reluctance.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.