Leveraged-Loan Pushback Is Too Little, Too Late

Leveraged-Loan Pushback Is Too Little, Too Late

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For fund managers, it’s easy to be picky when money is tight. It’s not so simple when they’re rolling in cash.

That’s the first thought that came to my mind when reading that leveraged-loan investors are suddenly willing to push back on the pervasive weakening of covenants, the safeguards in offering documents that are meant to protect creditors. Bloomberg News’s Sally Bakewell noticed this theme of increased selectivity running through the Milken Institute Global Conference in Beverly Hills as borrowers from Blackstone Group to Guggenheim Partners voiced concern over increasingly egregious loan terms.

This is hardly a new phenomenon. I wrote back in January that Moody’s Investors Service determined covenant quality in leveraged loans was the worst on record in the third quarter of 2018. It hasn’t gotten much better since. It’s “a trend we expect to continue and to leave investors exposed to greater risks than ever before,” Derek Gluckman, a senior covenant officer at Moody’s, said at the time, just weeks after the market suffered steep losses around year-end.

On Monday, the Federal Reserve echoed that sentiment, further amplifying its warnings about risky corporate debt in a twice-a-year financial stability report. “Credit standards for new leveraged loans appear to have deteriorated further over the past six months,” the Fed said, with its board voting unanimously to approve the document. “The historically high level of business debt and the recent concentration of debt growth among the riskiest firms could pose a risk to those firms and, potentially, their creditors.”

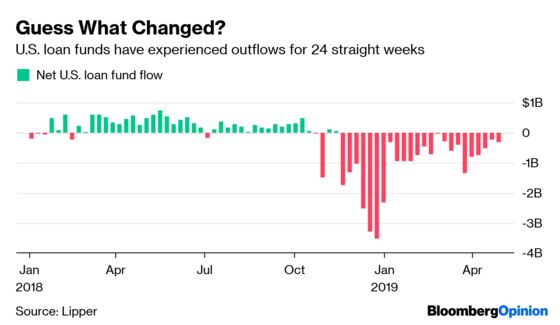

Are investors finally wising up? That’s surely part of it. But there’s one crucial piece of context that most obviously explains the heightened scrutiny: U.S. leveraged loan funds have had 24 consecutive weeks of outflows. That’s in stark contrast to almost all of last year, when money came pouring in largely unabated. Loans have trailed 2019’s broad rally in risky debt because they have floating interest rates, which are less appealing with the Fed on what appears to be an indefinite hold.

With that in mind, it seems obvious that Guggenheim would have attorneys analyzing loan documents along with its portfolio managers. And it’s only natural that other firms are strengthening their ability to assess investor safeguards. When there’s so much less pressure to purchase whatever comes to market, buyers regain the upper hand. Firms like Covenant Review have long been flagging risks embedded within the offering statements, such as highlighting a “particularly egregious loophole” that would “eviscerate fundamental protections” for investors in a $5.45 billion loan from Envision Healthcare in September. Occasionally, investors pushed back. Other times, they’d let things slide.

It might be too little, too late for investors to get tough on leveraged-loan issuers. Already, UBS Group AG estimates loan owners may end up recouping about 40 cents on the dollar in a downturn, potentially less than half what they’d historically expect to get. Moody’s has estimated recovery rates of 61 percent on first-lien loans and 14 percent on second-lien obligations in a recession, down from long-term historical averages of 77 percent and 43 percent, respectively.

Perhaps one of the more worrying parts of deteriorating covenant quality is how companies on the verge of serious distress can sneak up on unsuspecting investors, or take self-interested actions that creditors didn’t think possible. Bakewell highlighted a few such instances in the past few years:

J. Crew Group Inc., for example, started moving valuable trademarks out of the reach of creditors in 2016 as it was restructuring its debt. More recently, a $10 billion financing backing the buyout of a Johnson Controls International unit Power Solutions garnered criticism from some analysts for granting the borrower and its sponsors too much leeway.

Weaker covenants also mean investors might not see warning signs that something is wrong, said Guggenheim’s [Anne Walsh, chief investment officer for fixed income]. She cited bankrupt Toys “R” Us Inc., where the price of the company’s bonds remained high until soon before the company filed for bankruptcy in 2017.

“You had no real signal with regard to the covenants warning us as investors that something seriously was going wrong and that they should have been restructuring earlier,” Walsh said.

Saying investors had little warning of what was coming might be an exaggeration – after all, what are portfolio managers paid for if not to know what they own? But it’s hard to pin the blame entirely on them when private equity firms sprinkle provisions throughout massive documents that can come together to work against creditors in certain circumstances. When fixed-income investors were throwing money at leveraged loans hand over fist to ease the sting of rising interest rates, the options were to abide by the seller’s provisions or get shut out of the offering.

It’s certainly better for the long-term health of the $1.3 trillion leveraged-loan market that the pendulum has swung in the other direction. But it remains to be seen just how sincere investors are about banding together to strengthen covenant quality, especially if ebbing fund withdrawals flip to inflows. History has shown time and again that all it takes is a steady stream of cash to set in motion some otherwise objectionable deals. It’s up to investors to keep those impulses in check.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.