Kyle Bass’s Texas Feud Spotlights Short-Selling Tactics

Kyle Bass’s Texas Feud Spotlights Short-Selling Tactics

(Bloomberg) -- Ernest Poole had been dead for more than 60 years when someone opened an account in his name at an online platform called Harvest Exchange. Poole, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, was best known for his sympathetic pieces about the Russian Revolution. The platform was strictly for capitalists.

Poole was a pseudonym for Kyle Bass, a Dallas hedge fund manager who had taken out what amounts to a Wall Street bounty on a Texas real estate investment trust called United Development Funding. Best known for shorting subprime mortgages ahead of the financial crisis, a Powerball-type win that brought him fame and fortune, Bass had come to believe that UDF was a crooked company hiding losses amid fraudulent transactions with developers. His fund, Hayman Capital Management, had spent months building a short position that would pay off if UDF’s shares tanked.

In December 2015, using the Harvest Exchange account he had opened in Poole’s name, Bass published a blog post saying UDF was on the verge of collapse and calling it a “Ponzi-like scheme.” He signed it Investors for Truth.

Bass had alerted the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission, providing property records and photographs and urging them to investigate. Whether his arguments spurred them to act isn’t clear. The SEC, which was already scrutinizing UDF’s books, would later bring a case against the company. The FBI has also investigated, leading to a raid on UDF’s office in 2016. That probe is ongoing. But it was his anonymous post that triggered a cascade of events that brought UDF to its knees as its credit lines were cut and shares fell by 50% in two days. In Farmers Branch, Texas, where UDF was slated to help fund a $1 billion development, city finance manager Charles Cox feared the allegations could disrupt the property market in his tiny town about a dozen miles northwest of Dallas.

Bass made about $30 million on his bet, a person familiar with the returns says. But now, five years later, he’s embroiled in a lawsuit filed by UDF accusing him of defamation and interference with its business. And the same SEC office in Fort Worth that Bass reached out to is investigating whether he and his firm violated securities laws, according to two people familiar with the probe who asked not to be named because the matter isn’t public. The opening of an SEC probe is typically a preliminary step and doesn’t mean Bass, who hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing, will ever face an enforcement action.

There’s nothing illegal about making money by exposing suspected fraud. The government pays some whistle-blowers for doing exactly that. Activist short sellers, who stand to profit from a company’s collapse, do it all the time. They operate in a profession where it’s legal to use subterfuge, including fake names, while trying to move stocks. It’s also common to alert federal agencies. It’s even okay for short sellers to do all this without revealing their motives.

There’s just one catch: The short seller can’t knowingly spread false information. And that’s where UDF says Bass crossed the line. Its lawsuit, filed in state court in Dallas in 2017, alleges that his posts were misleading because the public was getting only part of the story—the part Bass wanted people to see.

Bass calls the lawsuit harassment and says he spared potential investors from plowing money into a corrupt company. His lawyer, Lawrence Friedman, says the SEC didn’t raise any concerns about Bass’s actions at the time and that any review now would result in “no action involving Hayman.”

The unfolding legal battle provides a rare look into a short-selling campaign. Hundreds of pages of documents and emails that have come to light show how Bass’s firm reached out to law enforcement and the media while trying to bend the market to where he wanted it to go. And they open a window on the symbiotic relationship between informants and the SEC, which looks to investors like Bass to help ferret out fraud in the marketplace.

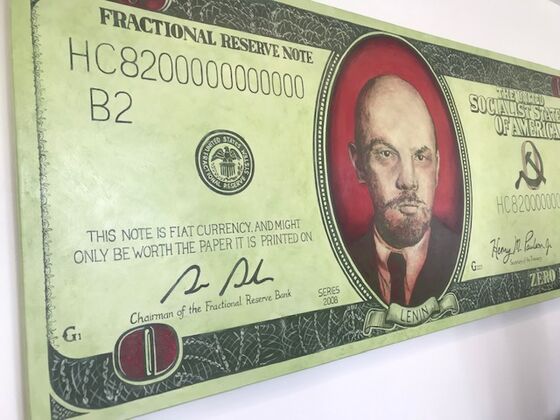

“We did everything right here,” Bass says, sitting at a conference table in his Dallas office last year, dressed in jeans and cowboy boots. A painting of a “Zero Dollar Bill” with a portrait of Vladimir Lenin and the words “United Socialist States of America” dominates the room. He calls it his protest about bank bailouts during the financial crisis. “We did our factual, financial and legal due diligence before we blew the whistle on UDF.”

A Texan by transplant, Bass, 51, grew up in a middle-class family alongside the children of wealthy oil barons with mansions, ranches and sports cars. While studying finance on a diving scholarship at Texas Christian University, he was often mistaken for a relative of billionaire oilman Robert Bass, who owned a fair amount of Fort Worth, where the campus was located.

Bass made a career focusing on event-driven trading, first at Bear Stearns Cos. and then at Legg Mason Inc. He specialized in coming up with stocks for his clients to short, doing his own research and sometimes providing SEC officials with information about potential fraud. He also got attention for some non-betting endeavors. In his 30s, he took part in the Gumball 3000 rally from New York to Los Angeles, driving a souped-up Porsche and winning an award for reaching 208 miles per hour in Nevada.

Bass started Hayman Capital in 2005 with $33 million and soon landed on what would become his biggest short: betting against the housing boom. He visited Wall Street trading desks and mortgage servicers and hired private detectives to dig into the sketchiest lenders.

While millions of people lost savings or homes during the crisis, Bass got rich. His subprime fund rose fivefold in two years. The win earned him instant credibility as a money manager and invitations to appear on financial news networks. By 2012, he was handling about $2 billion for investors including George Soros and Dan Loeb. He was featured in Michael Lewis’s 2011 book Boomerang, talking about the crippling levels of debt burdening the global financial system and the necessity of investing in hard assets, like guns and gold. He told Lewis he’d bought $1 million in nickels because the metal content in each one was worth 6.8 cents. The book described riding around Bass’s 2,500-acre ranch on the back of one of his U.S. Army jeeps, hunting beavers with infrared sniper rifles.

Bass relishes his position as a Dallas-based maverick. It has won him powerful friends, including former Trump advisers Anthony Scaramucci and Steve Bannon, Tommy Hicks Jr. and Hall of Fame quarterback Roger Staubach. But some of his bets after the financial crisis were losers, including those on General Motors and against the Chinese yuan. In 2014, as his fund’s performance waned, one of his analysts told him about UDF, a decade-old firm in Grapevine, Texas, about a 20-minute drive from Hayman’s office.

The company, which raised funds from investors and loaned them to developers at above-market rates, was founded by Hollis Greenlaw, a former Washington tax lawyer who, five years earlier, had pulled out of a real estate deal Bass was running. Although the financial crisis had wreaked havoc on developers and lenders, UDF was still paying dividends.

Bass’s analyst, Parker Lewis, learned about UDF from a friend, but at the time it didn’t have any publicly traded securities. Months later a large REIT raising money for UDF disclosed accounting errors, which prompted an FBI investigation. That led Lewis to question whether UDF was hiding its true financial situation. After months of research, he locked onto an explanation: When borrowers struggled to repay their loans, UDF used cash raised by newer funds to pay investors in older ones. Sometimes the newer funds would buy pieces of loans owned by the older ones in an effort to ensure that cash was available. These actions allowed UDF to keep paying the sizable dividends investors had grown to expect, which meant that it could continue attracting new investments.

To Lewis, it looked like a Ponzi scheme. By then, one of UDF’s funds had listed on Nasdaq and was a potential short target. Bass dismissed Lewis’s idea at first as being too small and too local. But Lewis was persistent. They had a massive fraud in their sights, he argued.

Short sellers have a long history of being hated. Critics accuse them of manipulating the market. Defenders say they keep businesses honest. Hedge fund managers like David Einhorn, Jim Chanos and Bill Ackman have come under fire from companies they’ve shorted. But the practice is as old as stock markets. Traders bet against the first public company, the Dutch East India Company, 400 years ago.

While long-term investors aim to buy low and sell high, short sellers do the opposite: They sell high and hope to buy low. First they borrow shares from investors willing to lend them for a specified period. If you’re Kyle Bass, you call up a bank to find these shares for you; smaller fish use online brokers. For this privilege, short sellers pay daily interest to the bank or the investors who owned the shares.

Then they sell the shares with the intention of buying them back when prices fall, returning them to the original owner and pocketing the difference. But if the shares increase, the short seller has to buy them back at a loss. While shares can only fall to zero, there’s no limit to how much they can rise, making short selling one of the riskiest wagers in finance. Ackman lost almost $1 billion before closing out his bet against Herbalife Nutrition Ltd.

Bass began shorting UDF in early 2015. That March he asked Hayman’s general counsel, Christopher Kirkpatrick, a former SEC official, to alert his contacts at the agency to a potential fraud. He provided a 17-page document that described UDF as having “characteristics emblematic of a Ponzi-like scheme.”

Sometimes the word “Ponzi” causes the SEC to spring into action, particularly in Texas, where the government missed opportunities to end what became a $7 billion scheme by Houston’s Robert Allen Stanford. But the response was muted, and in April, Bass called the FBI. The next morning a group of federal agents, SEC investigators and prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office in Dallas were getting a briefing in a Hayman conference room. By then, Bass was on the hook for 1.2 million borrowed shares of UDF, worth $21.3 million. Bass says he told his guests that he was short UDF and planned to short as many shares as he could get his hands on.

Over the next few months, Bass monitored the borrowing of UDF shares and directed his team’s interactions with government officials. “How many guys in suits?” he asked his head trader in a May email as his team was in the midst of a five-hour meeting with the FBI. When Lewis, the analyst, texted him pictures showing undeveloped land that UDF had funded, Bass responded, “I love it.” In another text, he wrote, “Make sure you send along the photos to SEC and FBI.”

But it was becoming harder for Bass to borrow shares, documents turned over by Hayman in the defamation case show. “Basically, we are moving the rate higher on ourselves,” Hayman’s head trader told him in a July 14 email. JPMorgan Chase & Co. was borrowing some shares for him at a 99% annual interest rate.

Bass ordered his team to short other companies he believed would fall on negative UDF news, investing $58 million in that effort. He considered a plan to set up a distressed-debt fund to buy bank loans backed by UDF assets that would trade at a steep discount if the company filed for bankruptcy. And he sought partners and investors from Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Blackstone Group Inc. and Crow Holdings, according to Hayman emails, though he never followed through with the plan.

By November of that year, 11 months into the short, UDF’s share price had barely budged, and the government hadn’t acted. Meanwhile, the cost of holding the short was mounting. In a Nov. 24 email to Bass, Lewis said Hayman was spending $84,000 a day, or $2.5 million a month, to maintain the position. He urged Bass to go public with his allegations about UDF. Bass’s response was unequivocal: “This will happen in December one way or the other.”

In early December, sitting on 3.4 million borrowed shares worth about $59 million, his traders under orders to “short as much UDF everyday as we can,” Bass decided to make his move. He posted the first Investors for Truth blog Dec. 10. It was headlined “A Texas-Sized Scheme Exposing the Darkest Corner of the REIT Business.”

Harvest Exchange, where the blog appeared, is the hedge fund industry’s answer to Medium or Forbes, a place where people publish investment advice, sometimes anonymously. Third Point’s Loeb, a backer of the platform, first touted his long position in Dow Chemical there in 2014. Bass, an early investor in the Houston-based site, used his real name to post research on why GM was due for a comeback.

The first post about UDF was cited on Seeking Alpha and ValueWalk. Short seller Andrew Left, who runs Citron Research, tweeted that the stock could go to zero. Shares dropped to $9.46 from $17.60 that day, wiping out about $237 million in shareholder value. That caught the attention of other media, including the Dallas Morning News.

It also caught the attention of UDF’s Greenlaw. He was preparing for a holiday party when the phones began ringing. “Fireballs from hell,” says Greenlaw more than four years later, recalling the mood shifting that day from festive to disbelief.

A conference room in his Grapevine office has been converted into a war room. A George Patton quote about courage is taped above a dry-erase board shrouded from visitors with a black cloth. “He preyed upon us,” Greenlaw says, gesticulating with his long arms, pulling pages from binders stuffed with documents, occasionally banging on a table.

As shares plummeted, UDF issued a press release saying that an unnamed hedge fund was trying to manipulate the share price. And it disclosed for the first time that the SEC had been combing through the company’s books since April 2014.

The next day, as banks began pulling UDF’s credit lines, Bass struck again with another Investors for Truth post that compared the company to Enron Corp. and Bernie Madoff. Then, on Dec. 15, he wrote that Greenlaw owned a private jet with Mehrdad Moayedi, CEO of Centurion American Development Group, UDF’s biggest borrower and one of Dallas’s largest developers, a sign that their relationship was closer than arm’s length. Before the end of the month, Centurion cut UDF out of the Farmers Branch project.

By using a pseudonym and not revealing his position, Bass opened himself up to scrutiny that he had something to hide. He says he wanted to protect his family and employees. But Hayman prepared a press release, which was never sent, explaining that the company made its allegations anonymously so they would be judged by their content, not by the messenger. A Dec. 28, 2015, email from Lewis to Bass called it “downplaying our status as an evil short-selling hedge fund.”

The SEC in recent years has taken a more aggressive position with articles and posts about publicly traded companies where the financial incentive of the author isn’t disclosed. But enforcement has been limited to pump-and-dump schemes. John Coffee, a securities law professor at Columbia Law School, said regulators have been loath to go after short sellers because they have First Amendment rights to publish their opinions, even under a pseudonym.

The agency, though, has gone after a few short sellers who tried to move a company’s stock with a false narrative. In one 2011 case, the SEC and the Justice Department said Barry Minkow, who had been working as a government informant, used his law enforcement ties to spark an investigation of homebuilder Lennar Corp. on false allegations about the company and its executives. He was also accused of spreading misleading information through a website. Once the investigation was underway, Minkow shorted Lennar. He pleaded guilty to stock-manipulation conspiracy—he was working with a disgruntled homebuilder who said Lennar owned him money—and was sentenced to five years in prison.

UDF alleges in its 2017 defamation case that Bass did something similar, knowingly publishing false information and deliberately ignoring the truth about the company’s finances. The lawsuit says Bass cherry-picked loans that weren’t generating cash from SEC filings, while omitting those that were. It also says Bass distributed photographs of overgrown brush to make the point that a project north of Dallas wasn’t being developed when publicly available information, including a Google Earth satellite view, shows that roads were being cut and dirt graded.

Bass says he stands by all of his posts and comments about UDF. In February 2016, two weeks after his role became public, dozens of FBI agents showed up at UDF’s office and hauled off documents in a rented Penske truck. News of the raid sent shares below $4 before trading was halted.

Two years later, the SEC brought a case against UDF and five executives, including Greenlaw, claiming they misled investors by failing to disclose that at times the company lacked the cash flow to pay distributions and instead borrowed money from other funds without disclosing how it was being used. UDF also loaned money from a newer fund to developers who still owed money to an older fund and directed them to use it to pay down earlier loans, the SEC said.

The allegations mirrored those made by Bass. But the SEC didn’t call UDF a Ponzi scheme and it allowed the company and its executives to settle the civil case for $8 million without admitting or denying wrongdoing. Greenlaw and others remain under criminal investigation by the U.S. attorney’s office in Dallas, according to Paul Pelletier, a lawyer for UDF.

Pelletier is trying to force the government to turn over nonpublic documents about the investigation to show that Bass inappropriately influenced prosecutors. The U.S. attorney’s office responded in an August court filing that UDF has a vendetta against the government and is trying to interfere with “legitimate law enforcement activity.” The company is also facing lawsuits brought by disgruntled investors and former partners, including Megatel Homes LLC—more evidence, Bass says, that the allegations he made are true. UDF has moved to dismiss those claims.

Pelletier says Bass is the one at fault. “It took a legal action by UDF to expose Bass and his unlawful and cowardly scheme to destroy UDF and harm its investors,” Pelletier says. “The government has refused to admit they were used by Bass. It’s time for them to focus on the true culprits.”

UDF hasn’t reported earnings in four years, an unusual lapse, though it is still collecting management fees. Greenlaw says reports by new auditors were delayed by the SEC case and a dispute over whether it can file earnings for the outstanding years in one report. In March, former auditor Whitley Penn paid a $200,000 fine and three of its accountants were penalized after the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board found that the firm failed to follow appropriate standards when auditing UDF funds from 2012 through 2014. In August, the SEC said that UDF’s recurring failure to file returns was done “with a high degree of culpability.”

“The fact that UDF hasn’t filed any of their SEC-required financials for almost five years tells me they don’t want to, or can’t, disclose how much of their investors’ money is missing,” says Bass, who has spent almost $4 million defending Hayman against UDF’s claims.

Those legal bills will likely increase. Last year, a Texas appeals court upheld a judge’s decision to let the defamation case proceed. Bass had argued that the gist of his posts was substantially true and that there was no basis to claim he had knowingly spread false information—a high bar that has to be cleared in such cases. But the appeals court said there was some evidence Hayman may have done just that. It also said there was evidence the hedge fund didn’t want to be identified “so that its statements would be more certain to plunge UDF’s stock value, resulting in a huge profit to Hayman, which, in fact, is what happened.”

While profit motive alone isn’t a factor in deciding defamation, the judges said, it can be used to assess state of mind. Bass sought a Texas Supreme Court review of the appellate decision on the grounds that it wrongly ruled on protected anonymous speech and UDF’s malice claims. His petition was denied without a hearing, and discovery is continuing. Bass says UDF can’t win without revealing financial information the company hasn’t provided. A trial has been set for January 2022.

Bass says he didn’t make a lot of money on the short—about 10% of the firm’s profit in 2016. But it “cost us five years of legal battles, distraction, aggravation and expense,” he says. “Given the friction imposed by this frivolous suit, Hayman will be forced to rethink ever blowing the whistle again.”

Meanwhile in Farmers Branch, new homes and apartment buildings have sprung up on the land UDF was supposed to help develop. Rudy Giuliani, a lawyer for President Donald Trump, was flown in by homebuilder Megatel in 2018 to help sell some of them. But there have been complaints that the $1 billion Mercer Crossing project was falling short on promises made by developer Centurion American.

In late July, Cox, the former finance manager and now city manager, was among Farmers Branch officials who attended a hearing about the delays. Sitting in the front row, wearing a blazer and a face mask, was Bass. A day earlier, he announced he had acquired a stake in several Centurion projects—Farmers Branch not among them. Bass said in a press release that his interest, which he obtained from a former Centurion partner, was “an opportunity to invest in distressed real estate projects” and that he was “dedicated to dismantling the fraud that has plagued these projects in the past.”

When the mayor asked whether the deal could impact the Farmers Branch development, Centurion’s Moayedi, a target of Bass’s UDF posts, said Bass would have nothing to do with the project. “Hayman Capital is a sideshow,” Moayedi said. “It’s a joke to even be here.” Moayedi said in a subsequent phone call that the projects Bass invested in weren’t distressed and that the accusations of fraud were bogus. “We’ve kept ourselves clean,” he said.

Bass says buying a stake in the Centurion projects is part of his effort to find out where the UDF money went—hoping it will give him access to records and business relationships he otherwise wouldn’t have. “I’m going to win this lawsuit if it’s the last thing I do,” he says.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.