It’s Not The First Time OPEC Has Pulled Up a Chair for Texas

Texas oil regulator Kent Hance met with OPEC in Vienna in 1988.

(Bloomberg) --

The crisis in the oil industry is so bad that Texas regulators are weighing whether to coordinate production cuts with OPEC. If they’re looking for advice, they should look no further than the man who first went to Vienna on behalf of the state’s oil industry.

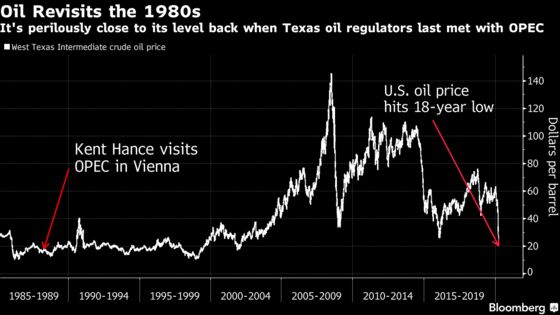

In 1988, Kent Hance, a member of the Texas Railroad Commission, boarded a plane to meet with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Back then, crude was trading in the teens, threatening the future of his state’s main industry.

“It was tough times,” Hance, who now has his own law firm in Austin, recalled Friday. “At the time, I told people, if I was a carrot farmer and there was one group that set the price of carrots, I’d know those people.”

Hance was the first Republican member of the commission, which was established in the 1890s, and the first to attend an OPEC gathering. He was also the last, though that may change. Commissioner Ryan Sitton was invited to attend a June meeting following his proposal to curtail Texan oil production in coordination with Saudi Arabia and Russia. Sitton held a one-hour phone call with OPEC Secretary General Mohammad Barkindo and spoke with White House advisers Friday, though no specifics were agreed.

“My recommendation is we come to the table,” Sitton said in a telephone interview. “An exceptional situation calls for exceptional solutions.”

Such an idea would have seemed unthinkable a few weeks ago. But the failure of OPEC countries and Russia to agree on further production cuts in Vienna earlier this month triggered what has now become a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Coupled with the demand destruction wrought by the coronavirus, that drove U.S. oil below $20 per barrel on Friday, far below the price American shale producers need for newly drilled wells to generate cash. The industry in Texas is already laying off tens of thousands of workers, according to Sitton.

While Sitton’s proposal of cooperation between the freewheeling Texas oil industry and a cartel of state-run producers might seem incongruous, it harks back to a particular period in the commission’s history. Following a slump in the oil market in 1931, the agency started periodically implementing a process known as pro-rationing to bolster prices. That ended in the early 1970s, just as OPEC, which had modeled itself on the commission, was rising to a dominant position in the oil market.

“I didn’t have to explain what the Texas Railroad Commission was,” Hance said of the “three or four” meetings he attended in Vienna. “They all laughed and said, ‘That’s how we figured out how to do this.’”

Sitton is one of three elected commissioners, all Republicans, who run the agency. He has proposed Texas curb its oil output by 10% in conjunction with an equivalent move by the cartel that controls more than one-third of global production. He faces several hurdles back home, including push-back from some oil companies and doubts from his fellow commissioners. EOG Resources Inc., one of the largest shale oil producers, called the plan “impractical.”

“A lot of people, rightly so, are very apprehensive,” Sitton said. “Our constituents elect us for situations like this and look at how we solve problems. They don’t need people who sit on the sidelines when you’re in an economic catastrophe like we’re in right now.”

Scott Sheffield, chief executive officer of one of the Permian Basin’s biggest producers, Pioneer Natural Resources Co., is in favor of Sitton’s proposal, which he argues would help save an industry upon which the U.S. economy relies.

“The reason we should participate is for national security so we do not have to participate in future wars in the Middle East and have to send our sons and daughters back to war,” he said.

There’s a key difference between the meetings Hance attended in the late 80s and the one Sitton may attend in a few months: Hance wasn’t pushing for a coordinated production cut.

“We were not producing that much, so we wouldn’t have had as much of an impact,” he said. He was just there to try to get the other members to stabilize the price of oil.

Texas -- and U.S. -- oil production has changed dramatically since Hance’s trip to Vienna. The advent of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology has unlocked the riches of shale rock, allowing the U.S. to reassert itself in recent years as the world’s biggest producer and a major exporter.

This time around, Hance said he’s in favor of considering curtailments back home.

“I’m all for free markets, but you should not allow your state resources to be given away,” Hance said. He fears this most recent collapse in oil prices will be “just as bad, if not worse” than the one the state suffered in the 80s.

“I would encourage the others to at least have a dialogue with them,” he said. “These are very tough and scary times.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.