Downgrades Are Rattling Jittery Investors in the Junk Market

Downgrades Are Rattling Jittery Investors in the Junk Market

(Bloomberg) -- Junk-bond traders aren’t known for reacting to credit-ratings changes. They’ve traditionally thought of themselves as smart enough to anticipate such events before they happen. But in a sign of how jumpy investors have become after one of the longest credit booms in history, that’s starting to change.

When firms like Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings have downgraded junk bonds over the last year, the debt markets have reacted unusually strongly, according to research from Barclays Plc. In September, for example, Moody’s cut U.S. Steel Corp.’s bonds one step, and over the following month, its most actively traded notes fell about 7%, while the broader high-yield index was little changed.

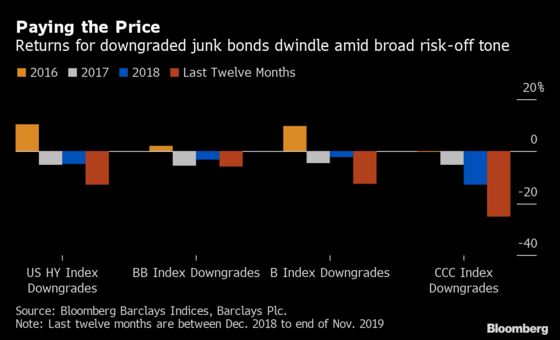

U.S. Steel isn’t alone. In the 12 months through the end of November, a high-yield bond downgraded at least one notch performed 13 percentage points worse than the Bloomberg Barclays High-Yield index on average, according to Barclays strategists led by Bradley Rogoff.

Usually, when a credit-rating firm downgrades a company, bond prices move much less, because the securities had weakened weeks or months earlier when investors first suspected trouble. In each of 2017 and 2018, bonds from a high-yield company that got cut would have lagged the index by just 5 percentage points, according to Barclays.

Investors may be paying more attention to high-yield ratings moves now because as junk bonds continue to rally to new highs, many money managers are getting more worried about the downside of owning notes that could default, according to Bill Zox, chief investment officer for fixed income at Diamond Hill Capital Management.

“In the late part of the cycle, it is especially important to avoid the land mines,” Zox said. “When a company trips up, the market shoots first and asks questions later.” Diamond Hill oversees around $23 billion in assets including junk-rated debt.

Read More in this Week’s Credit Brief: Junk Downgrades Rattle Investors

While money managers are still spotting trouble early and lightening up on their holdings of troubled companies, they are using downgrades as signals that they need to sell even more securities amid risks of a broader deterioration in credit markets, Zox said.

That may be why some of the biggest price declines after downgrades come when bonds are cut to what is essentially the lowest tradeable tier of high-yield debt, those graded in the CCC area, according to a Jan. 10 Barclays note.

Moody’s and Fitch Ratings declined to comment on the shift, while S&P said in an emailed statement that “ratings are one of many inputs that investors may consider as part of their decision making process.”

Deeply Entrenched

The growing importance of credit grades in the junk-bond market underscores how deeply entrenched the ratings firms are in the financial system, even after they played central roles in the last two credit crunches. Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch had investment-grade ratings on Enron Corp. just days before the energy trader filed for bankruptcy. High-profile failures like Enron’s and WorldCom’s helped trigger hearings in Congress.

After the latest financial crisis, enabled in part by overly optimistic ratings on bonds backed by subprime mortgages, another round of criticism ensued, with hedge fund manager David Einhorn saying “their brands are ruined.”

Junk-bond traders sometimes joke that only three ratings designations matter: investment grade, high yield, and default. While high-grade money managers pay closer attention to ratings, for decades, speculative grade investors might have only glanced at grades. They generally believed their job was to determine whether a bond’s price was low enough to compensate them for the risk they were taking, and not to anticipate whether a ratings firm was going to cut a bond to B from B+.

“Historically, ratings haven’t been an indicator of an investment theme,” said Sonali Pier, a portfolio manager at Pacific Investment Management Co., a firm that oversees around $1.9 trillion in assets. “We go beyond the ratings. Many times the ratings agencies lag.”

Downgrades Underperform

The last year seems to have been different. Downgraded bonds performed much worse, and upgraded junk bonds did a little better, although the difference there was more slight: upgraded notes performed on average 3 percentage points better than the index, compared with 1 percentage point in each of the prior two years, Barclays strategists wrote in an Oct. 25 note.

The biggest gains for upgraded notes come from those that leave the CCC category, according to the Oct. 25 note. Those securities can perform 10 percentage points better than the CCC index.

The credit fears that are driving these big movements after upgrades and downgrades are evident in returns for the year. The highest-rated junk bonds, those in the BB tier, gained nearly 16% in 2019, the most since 2009, according to Bloomberg Barclays index data. Those rated in the CCC tier returned 9.5%, including interest payments and price moves.

There may be reason to be alarmed. A measure of U.S. manufacturing activity in December fell to its weakest level since 2009, and the sector contracted for a fifth straight month. Also, elevated tensions with Iran could make investors more cautious. But since early November, many investors have grown slightly less worried about a recession, which has lifted Treasury yields a little higher. The service sector is expanding faster than many analysts had forecast.

Get Cautious?

Even putting macreconomic questions aside, it may make sense to be cautious now, just because prices have grown so elevated, investors said. U.S. junk bonds have been rallying for more than a decade. Since the start of 2009, the size of the market has more than tripled, to about $1.29 trillion, as companies have broadly borrowed more, and offloading bonds in any downturn may be difficult given how much debt is out there.

With the junk-bond market having grown so much, there are more potential risks for both companies and investors, said Michael Temple, director of credit research for the U.S. at Amundi Pioneer, which oversees about $86 billion in assets.

“There’s less of a margin for error if you own bonds now,” Temple said. “Companies that have a lot of debt don’t have a lot of time to improve results because we’re near the end of the credit cycle.”

If credit markets seize up, the lowest-rated borrowers may have trouble refinancing debt, potentially forcing them to file for bankruptcy. Those kinds of risks are leaving some investors “a little bit more on the edge than they were a few years ago,” according to Jody Lurie, a corporate credit analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott, which manages $90 billion.

“In those periods you are a little bit more attuned to any narrative to the positive or negative that relate to individual company stories,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Caleb Mutua in New York at dmutua@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at ngammeltoft@bloomberg.net, Dan Wilchins, Boris Korby

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.