In Bubbly Markets, Betting on Illiquid Credit Funds May Pay Off

In Bubbly Markets, Betting on Illiquid Credit Funds May Pay Off

(Bloomberg Markets) -- The Blackstone Private Credit Fund’s summary of risk factors reads like a compilation of investor nightmares: “You will not have the opportunity to evaluate our investments before we make them. … You should not expect to be able to sell your shares regardless of how we perform. … You may not have access to the money you invest for an extended period of time. … You will be unable to reduce your exposure in any market downturn. … You will bear substantial fees and expenses in connection with your investment.”

These conditions seem sacrilegious when Robinhood Markets Inc. makes moving in and out of positions as easy as a few taps of a smartphone, and discount brokerages provide free trading of stocks, options, and exchange-traded funds. BlackRock Inc. and Vanguard Group Inc. keep chipping away at ETF fees, while Fidelity Investments offers four index mutual funds with 0% expense ratios. These companies all say they’re trying to make investing cheaper and more accessible.

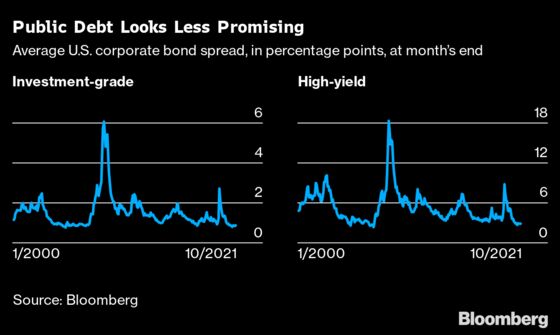

This frictionless financial system has drawbacks. Frothy valuations of ultra-liquid equities have spilled over into the crucial fixed-income market, where older investors traditionally park money for relatively stable returns. Risk premiums have vanished even for junk bonds, which spent most of 2021 at the tightest spreads to U.S. Treasuries since 2007. Nuveen LLC stopped accepting new investors for its high-yield municipal fund, the biggest of its kind, because too much money was chasing too few deals. And with long-term government debt rates at rock bottom, even as inflation hits multidecade highs, many market observers advocate buying pricey public equities, because “there is no alternative,” or TINA for short.

But what if the alternative is highly illiquid investments such as the Blackstone Private Credit Fund or similar offerings from the likes of Apollo Global Management, Carlyle Group, and KKR? Those companies, which traditionally raised funds from pensions, endowments, and other institutions, are aiming to manage more for individuals. Instead of trying to make a quick buck by scouring Reddit for the latest meme stock, savvy investors might be wise to give these products a look.

Private credit funds still have some of the barriers that have disappeared in public markets. The Carlyle Tactical Private Credit Fund requires a $10,000 initial investment for most share classes. Blackstone’s minimum is $2,500, and the fund also sets requirements for net worth and gross annual income. Although these thresholds are lower than they once were, they’re nothing like Robinhood, where the median customer has $240 in their account.

Still, private credit strategies can credibly claim to be a democratizing force by creating more opportunities for borrowers shut out from traditional financing sources. The sweet spot is so-called middle-market companies. This wide-ranging descriptor is sometimes used to define companies making from $50 million to $2.5 billion in annual revenue, or $25 million to $100 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, or Ebitda. Those businesses, particularly at the lower end of those ranges, might have the financial capacity to take on debt that can help them expand but aren’t large enough to tap the syndicated loan market.

In other words, these private-credit funds can connect borrowers and lenders that never would have met otherwise. Individuals can get investment returns that rarely exist in public markets, and borrowers receive financing at scale with terms that are more flexible than going through the usual syndication process with banks and prospective investors. These funds can distribute money in the private market instead of simply plowing cash into public corporations that may use it only for share buybacks.

“There’s a premium for complexity,” says Justin Plouffe, Carlyle’s deputy chief investment officer for global credit. “A lot of the transactions we do are highly bespoke. They’re not cookie-cutter—we get paid for that.”

The traditional option for midsize companies, of course, is banks. But regulations imposed after the 2008 financial crisis and the economic scars created by the pandemic have made many banks more cautious. In 2021 they started to loosen up. The Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices for the second quarter found lending standards had “eased notably since 2020” on commercial and industrial loans to companies of all sizes. Still, private credit managers pounced when banks held back, so much so that they say some companies are seeking funding from them first, rather than as a last resort.

“When companies don’t have the option to get the other money, we can lend and dictate terms,” Avenue Capital Management Chief Executive Officer Marc Lasry said at a conference in September. He said he prefers to fund those kinds of structured deals with small and midsize companies, which can offer double-digit yields, instead of wading into deeply distressed situations. Earlier this year, Pacific Investment Management Co. raised a $4 billion fund, its largest private corporate credit strategy, to look for similar opportunities.

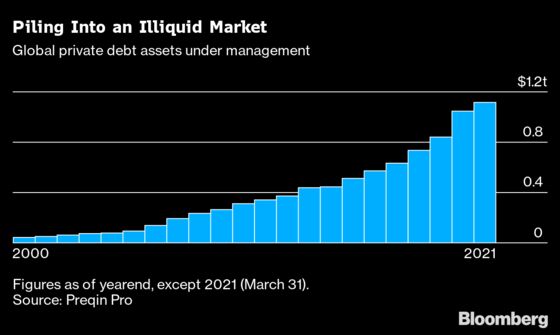

With more than $1 trillion of cash now parked in private-credit strategies, twice as much as in 2015, it’s natural to wonder when the tide will turn. Will asset managers gamble on too many bad businesses? Will they devolve into loan sharks when companies can’t make interest payments? Will individual investors be left holding the bag?

It’s impossible to know for sure. But strict lockup requirements of the kind imposed by these funds have paid off in the past. Private equity funds experienced a less precipitous drawdown during the 2008 financial crisis than public stocks. Studies attributed the outperformance to the funds’ flexibility in weathering the immediate shock. During another economic downturn, private-credit managers could defer interest payments or come up with another form of restructuring that would maximize long-term returns for investors without fear of sudden redemptions.

So-called zombie companies—loosely defined as publicly traded companies that don’t bring in enough money to cover interest expenses—might be more vulnerable. The ranks of zombies have swelled as bond markets allow them to keep rolling over their debt. A September report by consulting company Kearney found the number of zombies has expanded 9% globally in the past decade.

BY SOME calculations, zombies include brand-name companies such as Boeing, Exxon Mobil, and Macy’s, major components of bond indexes. The stampede out of fixed-income funds in March 2020 forced the Fed to take the unprecedented step of creating facilities to buy corporate securities. The not-so-subtle message: If borrowing costs spiraled higher and corporations couldn’t kick their obligations down the road, a wide swath of American businesses might fail.

The March 2020 episode illustrated the liquidity mismatch in credit markets during a bout of widespread selling pressure. It led Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to instruct the Financial Stability Oversight Council to look into how the open-end mutual fund structure can create “fire sales.” Managers of private strategies, by contrast, won’t have to return clients’ cash immediately because of the lockup agreements.

Markets face “more uncertain, volatile, and divergent growth and inflation than in the New Normal decade leading up to the pandemic,” Pimco’s Joachim Fels, Andrew Balls, and Daniel Ivascyn wrote in an October report. In the face of more muted returns on stocks and bonds, “we will look to take advantage of the illiquidity premium by pursuing opportunities in private credit, real estate and select developing capital markets,” they wrote.

The textbook formula for a bond’s expected return is to add on top of the real risk-free interest rate the market premiums for inflation, default, liquidity, and duration, along with some others depending on the security. Most measures appear stretched to their limits. The fed funds rate seems likely to be locked near zero until at least mid-2022, whereas inflation remains elevated, resulting in the lowest real interest rate since the 1970s. Junk bond spreads imply a sanguine outlook for defaults. The Treasury yield curve has flattened dramatically, offering investors little incentive to buy longer-term maturities.

Now there’s no clean measure for the liquidity risk premium embedded in a private-credit fund relative to a corporate-bond ETF or a benchmark Treasury note. But evidence suggests the yield pickup can’t be less than the other components. The Class I shares of Blackstone’s fund, for higher earners, gained 9.9% in the first nine months of 2021, while the Carlyle Tactical Private Credit Fund has provided a quarterly net yield between 7% and 9.04% on an annualized basis since the end of 2018.

Some other details: Blackstone’s fund is 99% in floating-rate debt, and Carlyle’s is at 88%, meaning they won’t lose if interest rates increase. Both are most heavily concentrated in lending to software companies, at 14.1% and 13.6%, respectively, but are otherwise largely balanced across industries. Blackstone is almost entirely in senior secured loans, and Carlyle’s fund is a blend of direct lending, liquid credit, opportunistic credit, and structured products. Blackstone has a 1.25% management fee and incentive fees of 12.5% on net investment income and realized gains net of realized and unrealized losses; Carlyle has a 1% management fee and a 17.5% incentive fee charged only on investment income net of expenses.

The Blackstone fund’s biggest holding is Cambium Learning Group, an education software company that brought in about $122 million in revenue in the first nine months of 2018 as a public company (ticker ABCD) before it was purchased by private equity firm Veritas Capital.

As of March 31, Carlyle’s fund had loans out to Anchor Hocking, which since 1905 has manufactured glassware in Lancaster, Ohio; TruGreen, a lawn services company in Memphis; and Higginbotham, a 73-year-old insurance agency that began in Fort Worth.

As more investors enter the private-credit world, scalability remains a question. Are there enough suitable small to medium-size borrowers to absorb all the cash looking for a home?

For now, Blackstone is looking “upmarket,” targeting larger companies that could issue debt through public channels and persuading them to borrow privately instead. The pitch: We may ask for a higher yield, but you’ll save time by skipping an investor roadshow and waiting around for credit ratings. Plus, there’s no sweating over market conditions or whether buyers will show up.

At their heart, private credit funds create a real market in every sense of the word by bringing borrowers and lenders together to negotiate fair terms for both sides, without relying on intervention from central banks or governments. Maybe that’s a scary thought for some investors who have come to depend on the Fed having their back for the better part of a decade. But for those who are eager to get properly compensated for taking risk, Blackstone, Carlyle, and their peers are ready to punch their tickets aboard the private-credit train.

Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. This column doesn’t necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.