If Supply and Demand Set Stock Prices, U.S. Market Has a Problem

If Supply and Demand Set Stock Prices, U.S. Market Has a Problem

(Bloomberg) -- The U.S. stock market has been staging a vanishing act for years. Which is to say, it’s gotten smaller, due to a combination of takeovers, buybacks and fewer new listings. Investors don’t mind this. They often cite the contraction as part of a bull case premised on scarcity.

Something is happening to tilt the calculus against them.

While American firms almost always repurchase way more stock than they sell via offerings, May was different, as deals by Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. glutted the market with new supply.

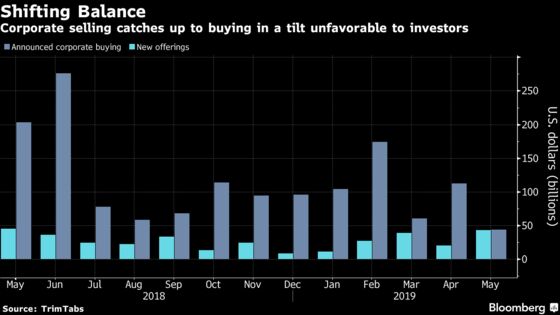

All told, U.S. companies announced plans to sell $43 billion of stock via initial and secondary offerings last month, roughly matching the amount they said they would remove via buybacks and takeovers. Only twice in the past six years has issuance exceeded supply, according to data compiled by TrimTabs Investment Research. For context, about $4.30 had been bought back for every $1 raised, on average, over the past year.

In a world where a trade war rages, bond yields are falling and every Federal Reserve utterance is combed for its interest-rate implications, it’s easy to dismiss swelling share issuance as a mortal threat to the rally. Not everyone sees it that way. The shift in the market’s supply and demand dynamic plays into a host of late-cycle anxieties in which companies pressure buyers with last-ditch efforts to cash in on stretched valuations before they deflate.

“Companies are looking at this as a great time to unload shares rather than to buy shares,” said Winston Chua, an analyst with TrimTabs. “You’re removing the buffer from the market that’d normally prevent more dramatic declines,” he said. “That’s usually a bad sign.”

Some 26 companies made debuts in May, driving total share sales to $43 billion. That’s more than double the previous month. On the other side of the ledger, demand is dwindling. Announced buybacks and takeovers tumbled 61% as corporate profits fell and President Donald Trump escalated a trade war.

For investors who believe companies are a crucial source of price support, the shift is worrisome. At times of trouble, companies appeared to have helped keep losses in the stock market from snowballing. The market’s bottom in February 2018 came in a week when Goldman Sachs’s corporate-trading desk saw the busiest buyback orders ever.

The role of buybacks in boosting the overall market is hotly debated. According to strategist Ed Yardeni, the benefit is overblown. Most repurchases are carried out to offset shares issued as employee compensation, he argues. During the eight years through 2018, buybacks reduced share count by only 1.1% a year. And there were little noticeable performance differences between S&P 500 companies that did and didn’t see their share count contract, according to a recent study by his firm, Yardeni Research.

The impact of buybacks “has been greatly exaggerated,” Yardeni wrote in a note last week.

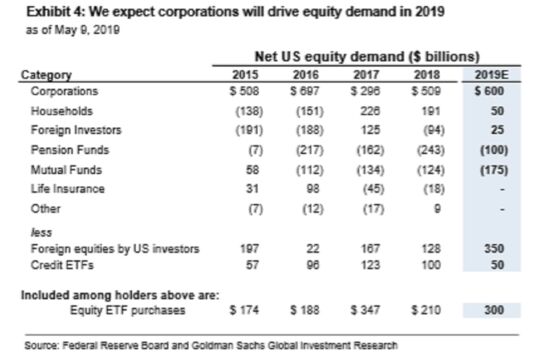

On the other side of the argument is Goldman Sachs, whose strategists led by David Kostin say companies have become the biggest buyer of stocks. Since 2010, net buybacks averaged $420 billion annually, far exceeding the combined purchases from households, mutual funds, pension funds and foreign investors, Federal Reserve data compiled by Goldman showed.

Kostin’s team, however, is not concerned about the surge in share issuance. While 2019 has a shot at achieving a record year of initial public offerings, it’s no match for the buybacks companies will execute. Primary share sales will reach $80 billion for the whole year, compared with net buybacks of $600 billion, Goldman estimates showed.

“Corporate buybacks will remain the largest source of equity demand and should still be only modestly offset by equity supply from U.S. IPOs,” Kostin wrote in a note last month.

That doesn’t mean it’s without risk. The market has developed “an unhealthy dependence” on buybacks and the danger is when companies aren’t able to sustain the pace of repurchases, according to Vincent Deluard, a strategist with INTL FCStone Financial.

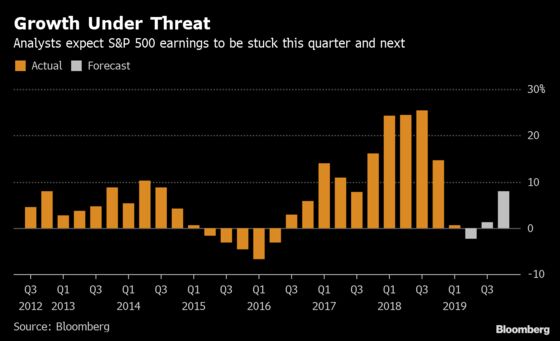

Earnings in the S&P 500 came very close to falling in the first quarter, and analysts expect growth to be virtually zero for this quarter and next. Any exogenous trauma would make it worse.

In 2000, an exodus of individual investors exacerbated the bursting of the internet bubble. In 2007, corporate buybacks were booming. But as the global financial crisis spread, write-offs ballooned, profits sank, and companies including banks quickly turned to share sales to shore up their balance sheet.

“Companies typically increase buybacks when cash flows are strong and liquidity abundant but cut them quickly in times of economic and financial stress,” said Deluard. “Buybacks could have the same pro-cyclical effect as retail investors did in prior bear markets.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Lu Wang in New York at lwang8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brad Olesen at bolesen3@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi, Jeremy Herron

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.